Nova Scotia's electricity supply needs to get a lot more sustainable---it's the law. The Environmental Goals and Sustainable Prosperity Act demands that within six years we use more than twice as much electricity from renewable sources as we do now. And wind is an obvious way for us to get there.

Unlike the province's other potentially major green energy source, tidal power, wind power is a mature technology that's already serving communities around the world. This blustery province has the physical potential to be one of the world's wind energy hotspots, and because it's sparsely populated there are plenty of places where planting windmills won't disturb people. Yet today only one percent of Nova Scotia's electricity comes from wind, and while many projects have been proposed and accepted, only a fraction of them ever come online.

One proposed wind farm site is south of the Bras D'Or Lakes in Cape Breton, on a 1,000-hectare wetland and hammerhead-shaped lake. Lake Uist is a beautifully rugged area, home to eagles, bobcats, owls and many other wild animals, as well as spiritual home for the Eskasoni Mi'kmaq. Luciano Lisi, the project developer who was also producer of classic B-movie horror flicks like Island of the Dead, wants to put 44 new wind turbines around Lake Uist, producing 250 megawatts of energy---four times Nova Scotia's current wind production.

So what's the problem?

Actually, there are a few. There are serious environmental concerns about the backup hydro Lisi plans for when the wind isn't blowing, for instance. And the power grid needs to be upgraded to carry energy from rural Cape Breton to homes and businesses in the rest of the province. But these could be overcome, if the province and Nova Scotia Power could only see that a little investment now will save us all a lot of money down the road. Still, there's community opposition.

"This area has been used by Mi'kmaq for hunting, trapping, gathering and medicines for a very long time," says elder Albert Marshall of the Moose Clan, who lives in nearby Eskasoni. He says the Mi'kmaq must protect the land and water from such development.

Marshall's problem isn't with the windmills. He's concerned about the hydroelectric station that accompanies them. Using hydro and wind allows for storage of wind power during low-demand hours. When the wind is blowing but there isn't much demand, the wind power is used to pump water up hill, to the lake; when the demand is high but the wind isn't blowing, the water runs back downhill, through the hydroelectric station, to generate the needed electricity.

"It solves the important problem of wind variability," explains Lisi.

Hydro is a great backup, but Eskasoni, the Mi'kmaq and environmentalists challenge the location. The status of that Crown land and water is under negotiation with the Mi'kmaq First Nation.

"The Mi'kmaq are not anti-development, but this project is nowhere near green," Marshall says.

The Ecology Action Centre, which is generally pro-wind, agrees. "We are in favour of the proposed wind energy portion of the project," an EAC statement says. But EAC is concerned that the hydro portion as originally proposed would destroy the wetland, leach methyl mercury into the lake (possibly poisoning drinking water), create "probable disastrous effects for the aquatic ecosystem" and punch access roads through fragile wilderness.

The EAC suggests that "electricity can be stored in water reservoirs that are less ecologically sensitive, such as abandoned mines and quarries...as compressed air in caverns, or at a smaller scale in batteries or fuel cells."

Lisi disagrees. "Our project will have no effect on the lake, that's just idiots talking," he says. He says he's jumped through every environmental hoop, including impact assessments with the province and feds. He plans to break ground by 2010 and to gain EcoLogo certification, North America's highest green standard.

The Lake Uist proposal shows why only one percent of Nova Scotia's electrical generation comes from wind. You've got your top-down mega-project, unpredictable wind supply, lack of government involvement, the power monopoly shutting out a local producer and you've got strong community resistance.

And if Lisi succeeds, not a single watt of this energy will stay in province. Despite Nova Scotia's ambitious goal of achieving 25 percent renewable energy by 2015, it's easier and more lucrative to export wind power to the United States, because that country has better tax incentives for renewable energy than does Canada. Lisi hopes to sell his wind power to power companies in New England, possibly to Long Island Power in New York.

Electric Co.'s monopoly

Many would-be local wind producers consider Nova Scotia Power, the province's only serious energy buyer, an insurmountable stumbling block.

For its part, NSP is dogged by progressive renewable energy goals that were laid out broadly by the MacDonald government in the 2007 Environmental Goals and Sustainable Prosperity Act, specified as the Renewable Energy Standards under the Electricity Act later that year and upped by the Dexter government in July. Currently, we consume about 10 to 12 percent renewable energy, mostly hydro. (Renewable energy includes power from any source that can be replenished, such as wind, sun, biomass, hydro or tidal.) If NSP meets its targets, we'll have 13.5 percent renewables by the end of 2010, 18.5 percent by 2013 and 25 percent by 2015.

To meet these goals, NSP uses the request for proposal, or RFP, process. It's a cutthroat competition in which the lowest bidder wins a contract to produce energy at about half the price we pay for coal and oil. The winner operates on tiny margins and any deviation from the plan---like, say, a global economic meltdown---means the windmills don't get built.

"The contract gets awarded and government gets to say so much of our power will now be renewable," says Peggy Cameron. "But only half ever actually get built." Cameron is vice-president at Black River Wind, a Cape Breton wind firm owned by documentary filmmaker Neal Livingston.

The wind projects most often built are relatively small, under two megawatts. As a result, of 276MW (almost enough power for all of the homes in HRM) contracted between 2002 and 2004, only 63MW, or 23 percent of the proposed generating power, actually came online.

Since 2005, another $100 million in wind contracts have gone unfinished. Now, yet another 246MW of wind has been contracted with six different companies, but if the success rate holds true we can expect only about 60MW of that to come online.

NSP has a rosier outlook. "We're completely comfortable with where we'll be in 2013 and 2015," says Robin McAdam, executive vice president of sustainability.

The challenge, says McAdam, is the government's requirements that new renewable energy must be generated by independent power producers, which are struggling to find capital in the recession. This rule will change after 2010, allowing NSP to invest directly in wind projects, giving it the control McAdam says it will make implementation possible.

Cameron offers another explanation. "This is typical of other RFP jurisdictions," she says. "Problems are created because people underbid, they don't understand the real cost, or the cost parameters change."

Cameron describes a volatile, high risk industry in which only large, deep-pocketed operations survive. And because the contracts always go to the lowest bidder, companies throw together ridiculously lowball proposals and hope the stars align, while more experienced companies know they can't do it on the cheap. The contracts go to the lowballers, who can't actually build them at that cost, so nothing gets built.

The RFP process is widely regarded as a failure among renewable energy producers, and Cameron's company is a prime example of an experienced producer that can't compete. "We've been working on a project in Cape Breton for six years," Cameron says. "It's been shovel-ready for five years and we haven't been able to get a contract with the power corporation."

Cameron says NSP is clinging to an antiquated process it knows is failing. Because of the low-bid madness, wind turbines aren't getting built and renewable targets aren't being met. To compensate, NSP came up with an alternate plan and applied to the Utility and Review Board---our energy regulator---for approval of a 60MW biomass project with NewPage Corporation.

The biomass application came under heavy fire from environmentalists and the UARB itself, which called the plan incomplete and poorly documented. Environmental groups support using sustainable biomass, but they accuse NSP and NewPage of green-washing---using large-scale biomass harvesting, including clear-cutting more than 6,000 acres a year, to meet the province's renewable energy objectives.

McAdam admits that the decreasing likelihood of NSP meeting its 2010 goals was a factor in the push for biomass, but maintains that biomass is a legitimate renewable energy source. "It is a low-cost way to convert to renewables---to displace coal but still use the same equipment." He adds that unlike wind, biomass gives a predictable energy source that doesn't need to be supplemented.

The provincial government's announcement that NSP must reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 25 percent by 2015 will no doubt keep the company scrambling for low emission alternatives. In the meantime, without large-scale biomass on the table, NSP's focus is on purchasing approved wind projects that were never built from independent producers. To date, it has purchased seven such projects.

The hand that feeds

To meet provincial goals, we need 311MW of renewable energy (including wind, tidal, biomass, solar and hydro) by next year, 581MW by 2013 and 781MW---enough for more than 200,000 homes---by 2015, requiring about 390 wind turbines.

That's 349 more than we have now.

To get there, the NDP has long supported feed-in tariffs, which are pretty much the opposite of the low-ball RFP system. Feed-in tariffs provide a guaranteed price set by the government and paid by the power company to anyone who can feed the grid with renewable energy. This is the change wind producers and environmentalists say will shift the wind back in Nova Scotia's favour.

"With feed-in tariffs you know the rate of return you need," says Peggy Cameron. "It makes for a secure investment." That opens the market to smaller producers, which means more windmills, green energy that stays in the province and fewer coal and oil imports.

The Pembina Institute, a sustainable energy think-tank, says almost two-thirds of the world's wind energy has been installed because of feed-in tariffs. They are popular in Europe, especially Spain, Denmark and Germany.

"You simply go to the bank in Germany and fill out a two-page form on your project costs," Cameron says. That levels the playing field and opens the gates to new suppliers. And, according to Cameron, "The average cost in Germany of feed-in tariffs is only about two euros per month" over the cost of carbon-based power. She says that initial increase in cost is easily compensated by improved energy efficiency in the home and the creation of renewable energy jobs.

Germany invented feed-in tariffs in 1991. Prices were guaranteed at a set rate for 15 to 20 years. A thriving industry has resulted, with almost 20,000 turbines, often within 200 metres of people's homes. There are a quarter-million German jobs in renewable energy, more than 70,000 in wind alone.

In February, Ontario followed Germany's example and implemented feed-in tariffs under its new Green Energy Act. That province expects feed-in tariffs to create 90,000 green energy jobs.

NSP says it will work with a feed-in tariff system if it has to. "We don't really have anything against them," McAdam says. "If government wants them we're happy to administer them, but the question is what rate do you set?"

He says that Ontario set the rate at well above market value. "People there support it, but consumers here are very sensitive to price."

During last year's provincial election, the NDP promised feed-in tariffs for Nova Scotia. The party statement on the subject read: "A rate will be recommended to the Utility and Review Board in consultation with the renewable energy sector and Nova Scotia Power."

Energy minister Frank Corbett has since backtracked on that promise, opting instead for further consultation, assigning David Wheeler, dean of the management department at Dalhousie University, to "help bring together diverse audiences and get them to put forward ideas" on how to reach the new renewable energy targets.

Megan Tonet at the Department of Energy explains that feed-in tariffs will be part of that discussion. "Support for small-scale producers is a priority area for government," she says.

But still they must wait as the government conducts further studies.

Technical difficulties

The case for feed-in tariffs is compelling but even if the government and NSP do everything right, Nova Scotia won't meet its legislated renewable goals without first spending a lot of money on the power grid.

Presently, Nova Scotia can handle about 20 percent renewable energy with the current grid. Or, rather, the current transmission grid.

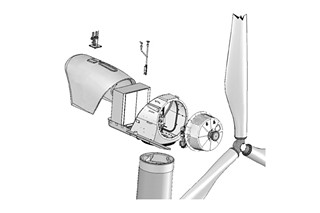

"There are two grids," explains Jamie Thompson, a mechanical engineer and wind-power advocate. "The distribution grid and the transmission grid."

The distribution grid is made up of the power poles we see in every neighbourhood, distributing power to homes and businesses. The transmission grid consists of large high voltage lines that run off the beaten track, transmitting power from generating stations to the neighbourhoods.

These high-voltage transmission lines don't always lead to the windiest places. "With the low-bid proposal system, you have to find the windiest place close enough to sizeable transmission lines," Thompson says. "This tends to be close to the coast, where you have a lot of settlement."

The result is that people living in coastal communities raise hell whenever a wind farm is proposed. Even if the project avoids ecologically and spiritually sensitive areas, like all energy generators windmills take their toll. They kill birds and bats and are noisy, they obstruct the ocean view, cause electromagnetic interference and annoying (some say nauseating) flickering shadows and have been known to throw off ice and an occasional blade.

Each turbine requires about an acre of land cleared, and wind projects often require new access roads. In Europe, where wind turbines have long been common, obsolete towers have been abandoned.

There are claims of chronic health problems from people living near wind farms, including high blood pressure and heart rates, depression, dizziness, migraines and memory loss. Some believe these symptoms are caused when wind turbines emit pulsations, which in turn create disturbing vibrations in people's chest walls and inner ears.

Wind advocates argue that none of these problems with wind generation compare to the health and environmental impacts of mining---Dan Roscoe of Scotia Windfields points to the annual $500 to $2,000 cost per taxpayer on health costs related to carbon energy---but the point remains that wind farms often encounter local resistance.

That location problem could largely be solved by expanding the transmission grid.

"The utility should be legislated to guarantee access to the grid," says Cheryl Ratchford at EAC.

That would mean that wherever someone builds a wind-farm, NSP would be required to build the transmission lines to the farm. And that costs big bucks. The Nova Scotia Wind Integration Study, released in May 2008 by Hatch, a multinational energy consultant, predicted it will cost $260 million in costs to upgrade Nova Scotia's transmission system to become wind-friendly.

Thompson says that is a modest investment given that NSP spends close to twice that on imported oil and coal each year. He says adding transmission lines from Canso to Halifax would create much of the needed wind capacity.

But even with improvements in the grid, there would still remain the variability problem. Wind is intermittent and doesn't guarantee a steady supply of electricity. Coal and oil are poor backups because to switch between them and wind requires reboots of the system that take several days.

With little hydro available locally, the Hatch study focused on importing electricity from neighbouring provinces to even out the supply and demand. The problem, according to lead researcher Robert Griesbach, is that "Nova Scotia's electricity system has limited interconnection with neighbouring provinces."

Megan Tonet at the Department of Energy says a lot will depend on hooking Nova Scotia up to hydroelectric power from sources like the controversial Lower Churchill mega-dams project in Labrador. But that project isn't due to come on line until 2015.

The Hatch study concluded we need another study, looking at the grid and energy ties with our neighbours. That $300,000 study is being conducted by SNC Lavalin, a multinational energy and engineering firm, and is expected to be completed in coming months.

A multi-provincial committee has also been struck to conduct yet another study, a two-year, $4-million study of alternative energy called the Atlantic Energy Gateway Initiative. The goal is to make the technological and policy changes needed to allow for the easy flow of renewable energy from one region to another. If it works, a small wind-powered community in Nova Scotia will be able to count on hydro or solar power from New England on a windless day.

But without that interconnectedness with other provinces, power can't easily flow either direction across the border. Potential wind power exporters like Luciano Lisi may build turbines, but the power they generate has nowhere to go. "Until the grid is strengthened with New Brunswick," says Tonet, "we do not expect to see large-scale exports of electricity."

So we're stuck in a wind impasse. Small wind companies like Cameron's and Roscoe's that want to sell power to Nova Scotians can't do so because they can't get the wind farms built. And big wind companies like Lisi's that want to export power can get farms built, but can't necessarily move the power to their out-of-province customers.

Robin McAdam at Nova Scotia Power says Lisi is just trying to find the highest value market, and that market will eventually be here. "The local market for green energy is growing steadily. Higher renewable targets here means more opportunities here."

In whose backyard?

Peggy Cameron objects to large-scale wind projects like Lake Uist that fail to help Nova Scotia kick its coal addiction. "Why would people put up with the industrialization of the landscape?" she asks. "There is an advantage to having many small producers. It creates distributed energy and greater flexibility."

Ideally, producers need a means of sharing energy, so if it isn't windy in Truro, the energy can be accessed from Canso.

Cameron says that the greatest benefit of multiple small producers is that it makes it easier to put control where it belongs: in the hands of communities. This is crucial because, as Dan Roscoe points out, even with Nova Scotia's dismal record on wind contracts coming through we're likely to double our number of wind turbines in the next 12 months.

"There will be more community opposition," Cheryl Ratchford says. "Already communities are seeing large scale wind projects and asking questions. In Europe there is better community buy-in because there is more consultation early in the process."

According to Cameron, Denmark's cooperative system is the best model for overcoming community resistance. "Eighty-five percent of their renewable energy projects are cooperative," she says. "Community ownership is the key. They see it as money in the bank."

The quintessential example is the self-sufficient farming island of Samsø, off the eastern coast of Denmark. Its 4,100 residents have gone fossil-fuel free in just 10 years. The key to its success? Co-ops.

The island's 21 wind turbines, which provide 100 percent of its electricity and also feed the Danish grid, are co-owned by the municipality of Samsø, local farmer-owned co-ops and small shareholders, including locals and mainlanders. The municipality's profits are reinvested in renewable energy projects, while farmers and shareholders are free to keep theirs. The cooperative arrangement provides a steady source of revenue for the whole community and increases acceptance of the turbines. You're unlikely to hear anyone on Samsø complain about the high cost of energy---the higher the better, in fact.

That mindset is the polar opposite of the typical attitude here, where politicians get elected placating energy fears by offering subsidized heat and electric, protecting us from the big bad power company.

Imagine if we flipped that trope on its head, got inspired by Samsø and created a co-op model in the Canadian heart of the cooperative movement: Nova Scotia. Imagine wind farms owned by some of the same people who have been fighting them: rural communities, farmers and First Nations' band councils. Imagine municipalities reinvesting wind profits into energy security programs for low income families and energy efficiency programs for everyone. Imagine residents owning wind-shares and putting wind-dividends in their pension plans. Imagine using wind energy where it's generated instead of shipping dirty coal up from Colombia.

Environmentalists argue that green energy is cheaper in the long run. But in the short term, with our grid needing an upgrade, renewables will cost more per unit than we pay now. As the Department of Energy and NSP amble toward our wind energy goals, they will take that concern seriously.

"Their biggest fear is rates going up," Roscoe says. "But by doing nothing they are ensuring rates will go up. The status quo will give the worst possible cost to consumers. It's basic economics: the cost of fossil fuels are going to go up as supply goes down."

Price does matter, especially for people walking a fine budget line and choosing between heat or canned beans in the dead of winter. As Matt Lumley, another communications officer at the Department of Energy, puts it, "Cost goes up and it's hard for low-income people and the businesses that employ Nova Scotians."

True. Unless of course they belong to a community that owns a little wind farm, or work for a company selling power into a better, greener grid.