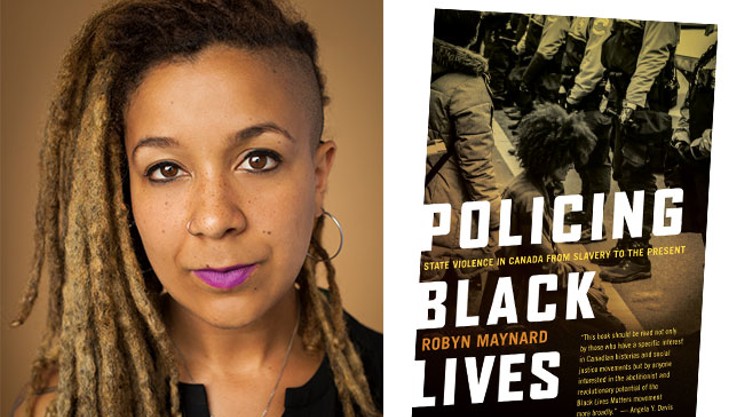

It was just about this time last year that Halifax Regional Police released a decade’s worth of statistical data on the use of street checks.

In the 12 months since the department has repeatedly shown it has a long way to go to combat racial bias both real and perceived in its policing.

But while efforts like the Human Rights Commission’s continuing investigation will examine police discrimination en masse, not much is being done to track and eliminate the racial bias held by individual officers.

Maybe there should be. New research from Princeton University shows that monitoring those individual incidents can be a fast and efficient way to effectively eliminate racial bias across the entire department.

According to an economics paper released late in 2017 by PhD candidates Felipe Goncalves and Steven Mello, the discretion with which police issue fines to speeding drivers can be an accurate early warning system for an individual officer’s racial bias.

The two analyzed how often Florida Highway Patrol officers show mercy by discounting a driver’s speed to just below a higher fine bracket and then compared that to the racial makeup of the drivers.

What they found was that the department’s overall racial discrimination could be accounted for almost entirely by 40 percent of its patrol officers.

Using their method, Goncalves and Mellow argue a police department could feasibly identify racial bias in its personnel very early in their career—within the first 100 tickets issued.

The excuse of a “few bad apples” causing all of a police department’s discriminatory behaviour isn’t a new

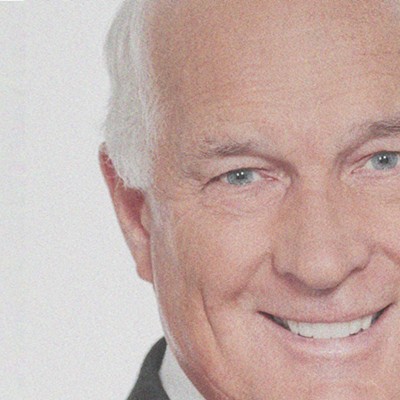

Halifax police chief Jean-Michel Blais, for example, spoke out in December at the Board of Commissioners about improving relations with the city’s Black community via department-wide training in fair and impartial policing.

“A lot of the issue seems to centre around the quality of the interactions between police officers and members of the community, and that’s the type of training that would allow us to look at many of the things that could cause friction in those interactions,” he said.

But Goncalves and Mello argue in their research that general policies are “only mildly effective” in reducing bias, and thus, creating a better police service. More important, it would seem, is being able to identify the worst offenders.

“Without knowing which agents are discriminatory, it is not possible for institutions to target individuals for discipline or training.”

As it stands right now, even armed with over a decade of data on officer behaviour at its research fingertips, HRP has no operational policies in place to track the racial bias of individual personnel.

“At this point, to my knowledge, there are no specific policies in place that talk about that, aside from the street check data we have,” Blais told reporters shortly before the holidays.

Aside from the compiled street check data, the only other avenue to check racial bias of individual police officers is the province’s formal complaint system.

Nova Scotia’s Police Complaints Commissioners’s Office receives hundreds of complaints each year from both members of the public and police officers alleging abuse of authority, corrupt practices and neglect of duty.

Halifax police, as the province’s biggest cop shop, make up most of those files. There were 87 public complaints and 37 internal complaints made against HRP officers in 2016 (the latest numbers available).

The majority of those were deemed unfounded, withdrawn or were found not to have met the statutory six-month time window to file a complaint.

Goncalves and Steven Mellow write that firing the most racist officers can help reduce racial bias, along with increasing departmental diversity (women were less biased on average than men). But the easiest solution to regaining public trust, the researchers argue, is reassigning officers so that minority communities are exposed to more a more respectful presence.

“Using a simple personnel policy that reassigns officers across locations based on their lenience, departments can effectively reduce the aggregate disparity in treatment.”

Both the Board of Police Commissioners and HRP committed themselves last year to addressing the use of street checks and improving the public trust that’s been eradicated from lifetimes of biased policing.

The Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission’s final report on the subject is tentatively expected by this fall.