Andre Fenton barely made it to class in his first two years of high school. But the poet and activist eventually graduated with honours after finding inspiration in an Afrocentric literature course he took his senior year.

“If it wasn’t for that class, I would not be doing spoken word poetry,” says Fenton. “It influenced me to be who I am today as an artist and activist. It really helped build a foundation.”

Fenton says he felt invisible throughout his school years because of the more Eurocentric curriculum he was being taught. Having a class to learn about the sacrifices his ancestors made motivated him and offered a sense of belonging.

That was just one class. Imagine, Fenton says, the kind of confidence Black students could have—the healthy environment they could learn in—if there was an entire school based

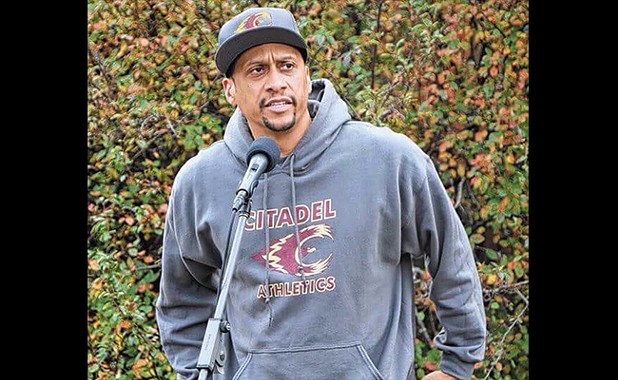

It’s an idea first introduced in the ’90s and brought up again in 2006 by Wade Smith. An African Nova Scotian educator and the principal at Citadel High School, Smith previously brought forward the idea of implementing an all-Black, Afrocentric school in HRM in 2006. The education system as it was back then was failing Black students, said Smith, who suddenly passed away earlier this spring after a battle with cancer.

Eleven years ago, Smith’s words were criticized, taken out of context and disparaged nationally. But Karen Hudson, president of the Black Educators Association, says Afrocentric eduction isn’t synonymous with segregation like many people mistakenly believed. It’s more about

“I’m a great believer in making children feel that they belong,” says Hudson. “When children feel they belong, they sometimes aspire to do better. Not just aspire, but they do better.”

It’s a belief shared by Halifax’s African Nova Scotian school board representative, Archy Beals. “It’s a whole way of thinking and a whole system that looks at how, we—people of African decent—value ourselves and a way of learning about ourselves,” he says.

Although Afrocentricity is sprinkled throughout the curriculum in all grade levels throughout the province, Beals says it’s still not where it needs to be. Most schools only offer Afrocentric classes in their senior years, but it’s not a mandatory course and works more like an elective.

The BEA addresses this issue by offering multiple programs that cater to and assist African Nova Scotian students attending public school. The Cultural Academic Enrichment Program and Math Camp strive to strengthen student’s math and literacy skills, but also make it a priority that students feel connected to a wider history that’s sometimes excluded from the public education system.

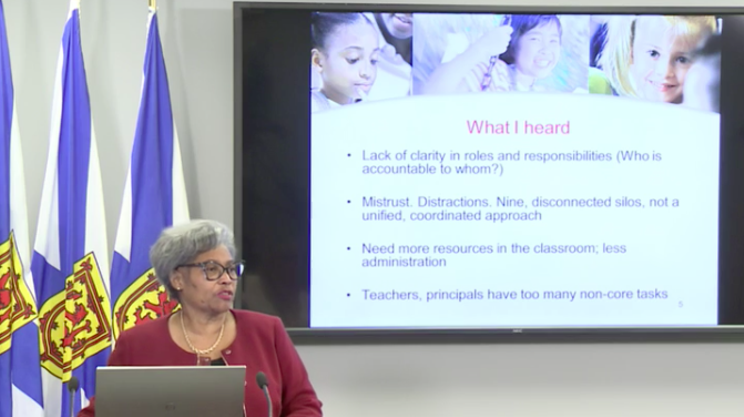

Hudson says one of the concerns that African Nova Scotian parents have voiced to the BEA is wanting teachers to get more training in recognizing their African Nova Scotian history, in order to create better teacher-student relationships.

Educators “have to take the time to get to know the students and to know what issues they face, their values and their cultural background,” explains Hudson.

Schools that cater to certain cultures and religions already exist in Halifax, such as the Maritime Islamic Academy, Shaar Shalom and the Francophone schools run by the Conseil Scolaire Acadien Provincial. That’s not too different than having an Afrocentric school.

Still, Hudson isn’t sure if “people are open to having an Afrocentric school” or if “there is a difference” these days from when Smith advocated for the idea a decade ago. People like Beals are instead working within the current system to develop initiatives addressing the challenges African Nova Scotian students face—such as achievement gaps, self-worth and the impact Individual Program Plans can have on students.

Reports in the past few years from the Halifax Regional School Board have shown African Nova Scotian students are disproportionately affected by suspensions and IPP programs.

“It has negative consequences if you’re looking to pursue further education,” says Beals.

Striving for more Afrocentricity within the current public school system has made some improvements, but according to Hudson, African Nova Scotian students are not progressing at the same level as the wider student population.

“If they are not succeeding at the same level, then we have to change some of the practices that we do and shift the paradigm,” he says. “You can't keep having the same results.”

Implementing an Afrocentric school, like the kind found in Toronto, is “past due” according to Beals, but that decision can’t be made without listening to the community and its wishes.

“We have a foundation, but we have to put up the walls to the house, and that house being an Afrocentric education.”

Wade Smith’s Afrocentric legacy

A decade after the beloved educator advocated for the idea, is Nova Scotia past-due for an Afrocentric school?

[

{

"name": "Air - Inline Content - Upper",

"component": "26908817",

"insertPoint": "1/4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - Inline Content - Middle",

"component": "26908818",

"insertPoint": "1/2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - Inline Content - Lower",

"component": "26908819",

"insertPoint": "100",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]