Two years ago Thursday, “some asshole broke into the Halifax Public Gardens and vandalized trees,” as captured by a headline that ran July 26, 2022 in the Halifax Examiner. The mystery of who did this is an unsolved whodunit.

Two years later, some of the trees that were girdled in the gardens—or intentionally had their bark stripped and deep cuts made into their trunks in a way that could kill them—have been removed from the gardens. Others, wearing life-saving strips of their own branches as grafted skin under burlap bandages, may still survive, though forever marked by this act.

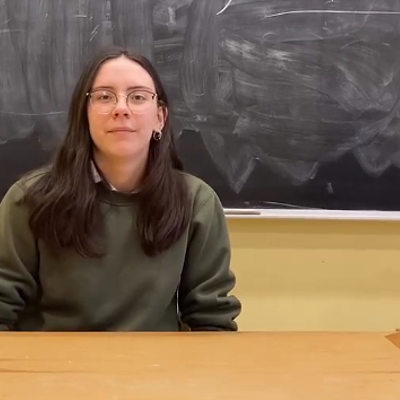

Artists Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux were in the gardens in the immediate aftermath of the vandalism. With the help of city staff, they took photographs of the injured trees without their bandages on.

These are now part of their show, Collective, at the Mount Saint Vincent University (MSVU) Art Gallery, on view until Aug. 17. The show documents various marks made on trees in different countries and locations—mostly through human intervention—that Bellamy and Fauteux have encountered.

The “process of accumulation” of hundreds of photographs of trees leading up to Collective, “was always in the background of whatever else we were doing for the last five years,” says Bellamy. They’ve distilled these into the exhibition at MSVU—the show's second location since first opening at the Art Gallery of Grande Prairie in Treaty 8 territory, in Alberta, on Oct. 5, 2023.

Bellamy and Fauteux are partners and artistic collaborators, currently splitting their time between Ōtepoti Dunedin in Aotearoa (New Zealand) and Sackville, New Brunswick, which is in Mi’kma’ki. Bellamy describes showing Collective in Kjipuktuk - Halifax as “really significant for us, because spending time at the [Halifax Public Gardens] is the moment where this exhibition coalesced.”

Before 2022, the artists had a large library of photographs to draw upon for what would become Collective, but until they were able to visit the girdled trees in the Halifax Public Gardens, these photos “were quite disparate,” says Bellamy. “We didn't, perhaps, fully understand the cohesion across that body of work.”

Bellamy describes their time spent in the gardens as “very poignant,” saying that “to be in the presence of the grieving community…reminded us about the importance of human relationships with trees.”

Now, Bellany says it brings them “a lot of pleasure” to be able to share their works with the community they formed those experiences with.

Within the exhibition at MSVU, maples and oaks from the Halifax Public Gardens share space with bamboo from Kawau Island, pine from Tuatapere, and eucalyptus from Te Whanganui-a-Tara/Wellington—all in Aotearoa (New Zealand)— as well as ash from Ndakinna/Vermont and aspen from Sturgeon Lake in Treaty 8 territory in Alberta.

The earliest photograph taken, says Fauteux, is called White Birch and is a tree in the Sackville Waterfowl Park in New Brunswick, which is within Mi'kma’ki. “As you enter the MSVU Art gallery, it's one of the first works you see,” says Fauteux, “and it has some light, nondescript scratches on the bark.” The work is a close-up photograph of marks on a birch tree trunk, framed in birch wood. All of the portraits are framed in the species of wood captured within.

The birch tree they photographed in their work is one of many that flank the boardwalk in Sackville that people have scratched their initials, “or little gestures of love to their partners,” says Bellamy, with various small tools.

The birch tree, in particular, caught their eye because the marks are more ambiguous, in comparison with another tree in their show where initials and a heart carved into the bark are more defined. With the birch, says Fauteux, “it’s kind of a scribble, and we just wonder what—”

“—what motivation or the rationale for the mark is when it’s a lot less clear immediately,” finishes Bellamy. “Those are the marks that really appealed to us, I suppose, are the ones that don't have an immediate answer.”

The gallery includes a printed-accompaniment to show, which is an essay written in 2023 by Amiskwaciwâskahikan Edmonton-based artist and writer Emily Jan, published online by Contemporary Hum.

Jan, who visited the show’s first iteration in Grand Prairie, describes site-specific “moments of intersection” between humans and trees within the works under five categories, including “I. Garden,” “III. Cemetery” and “V. Abbatoir,” as places where “we confront two forms of sentience, and two (or more) timescales, [while] each also represents a moment in which ideas collide—between what is considered natural and unnatural, between the bounded individual and the boundless system, between hieroglyphics and a world without language.”

Specifically, some of the trees photographed and shown at MSVU are from public park areas, says Fauteux, like the pine trees from Tuatapere, Aotearoa (New Zealand) with holes drilled in them.

“That's in a public park area beside a community orchard,” says Fauteux, “so, we went to see those on our own.”

Some of the trees that are featured in the show, however, are in places that weren’t easy for the artists to access on their own. “For us, that looks like building a relationship with someone who has a relationship to those trees, and then, through communication, trust and opportunity, they take us to see them,” says Fauteux.

That relationship building is an important part of their work and their practice more broadly, Bellamy says, “that allows us to realize and enable things that we wouldn't be able to do on our own and it’s something that we really enjoy.”

The MSVU gallery space is physically different from the space at Grand Prairie, and works are shown here in a new arrangement.

“We tried to randomize the order of this exhibition,” says Bellamy, “and that's not that easy because you find patterns and everything looks really deliberate and sometimes contrite.”

Bellamy says the process involves both artists “spending quiet time together in the galleries” while shuffling portraits around, “because we want there to be a sort of evenness in how people can approach each portrait—we don't want it to be a sort of grouping that becomes differently weighted.”

Rather, they want an ease for their audience in encountering the works individually and as a part of a whole, which requires “intuitive looking,” and allowing themselves time to walk away and come back with fresh eyes.

Another reason for randomizing the order “is to recognize that trees exist in a way where they're not discrete from each other,” says Bellamy. “They exist in forests with biodiversity and community and mycorrhizal underground networks—trees are in community.”

“And humans are also a part of those communities,” says Fauteux. “That’s kind of what the show is.”

There are 24 individual trees captured within Collective at MSVU, including “Maple” and “Oak” taken within the Halifax Public Gardens, shown in a video outside the main gallery doors. The other 22 appear as photographic portraits within the hall of marked trees.

The choice to capture the trunk segment of trees, and not roots, branches or treetops, “is, in part, informed by photographic traditions of portraiture,” says Bellamy. “We wanted there to be a subtle reference to a hall of ancestors, where the trees are captured, as if with the same respect that you might photograph a person.” What that looks like is portrait orientation and an “eye to eye” level between the works and their audience.

The tallest work is a four-photo piece called Gird, taken of a maple tree in the Halifax Public Gardens and spanning the two-storey wall in the MSVU gallery. This work is unique in its overall size from the other works.

Yet, “even with Gird, which does photograph up into the upper branches of a tree, we never capture a full portrait,” says Fauteux. “There's also everything that's going on under the earth with a tree, so there's a limitation to trying to take a portrait of it—so the framing is very much on this mark making.”

Bellamy says the size of the majority of works is also about showing the portraits “at a scale that has a bodily relationship to our audience.” The trees are photographed and hung in a way to represent their actual size and height, says Bellamy, because the ways that human bodies relate to these trees-as-subjects is part of what informs their artistic process.

One thing that Bellamy says has “surprised and humbled” both artists is the “pointed emotional reaction that some folks have had to the show,” which has manifested in people sharing tears at the exhibition openings at both Grand Prairie and at MSVU. “We knew that the work had some gravity—and we hope that it always does—but for folks to be that vulnerable that they would shed a tear, affects us, too, and speaks to the importance of our relationship to our environments,” says Bellamy.

When people see their show, says Fauteux, they “then tell us about their tree or a tree that’s very important to them, that they have a connection to, and those stories are always coming forward.”

One visitor in Grand Prairie told the artists that “he saw one of the works, in particular, as a mirror to himself and his journey of healing from severe PTSD, and the way that he noticed the new growth on the tree made him reflect on his journey,” says Bellamy.

This tree is the work Eucalyptus taken in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Wellington, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and appears as the second portrait to the left of the doors upon entering the MSVU gallery.

“That's one of the really nice things for us, and hopefully for our audience too,” says Bellamy, “is that it starts new conversations.

“It's not the end of something, it's the beginning of something.”

Sharing in the relationships between viewers and their favourite trees has been an enjoyable part of showing their works for both artists.

“And it continues to be,” says Bellamy. “It doesn't stop when the exhibition is realized and presented.”

Bellamy says they’re always looking for stories of marks on trees and, if they hear about one they’ll investigate further which “sometimes that leads to a dead end, or the tree isn't quite right for photographing for various reasons, but we're always open to the possibilities.” Bellamy says that when you do tune your ear to those stories, it’s “remarkable” how many of them there are.

As for the title Collective, Fauteux says “it's important that people can think about that in their own way.” You can think about it as the collective of trees that are in the exhibition, “so that together, they form a collective,” says Fauteux, “but also in the way [of] portraiture and relationship to the viewer in the gallery space that means you are also part of it.”

Fauteux says you can take the title “two ways or more—probably more because we like to think that there's also that relationship with other people that are experiencing the show, as well.”

Like all humans, says Bellamy, their own relationships with trees and other plant species is complex. As a potential continuum of the shows that the artists prepare, research and present, “we notice things in a different way and observe and interact with our environment in a different way.”

“We're always learning,” says Fauteux. Touching on a conversation within their work Collective and their artistic practice as a whole—that of historical and contemporary debates surrounding “invasive,” “exotic,” “native” and “non-native” plant species in different colonized countries—Fauteux says these points of contention and learning “introduce new complexities within more things we take for granted and things that we think we know, showing that there's always more to know.

“It's an ever-going process of learning, unlearning, noticing, seeing more.”

The artists don’t consider themselves photographers, having never worked with this medium before and saying they don’t plan to for their next show. However, they say documenting their works within Collective through photography came about because it was accessible and “the right process to realize this show,” says Bellamy.

Part of what motivates them to take on the role of photographer or documentarian of these trees, says Fauteux, “is to bring forward and unpack, complicate, implicate and share.”

There are two printed works accompanying the show at MSVU. One is the essay written by Jan and the other is a floor plan of the show within the gallery space and accompanying titles and land acknowledgements of each work.

The exhibition includes the following accessible features: ASL interpretation available on video in the gallery and on the exhibition webpage and audio recordings of exhibition text and artist statements which are also available on the website. There is ample seating, including chairs with and without arms and benches. Gallery attendants are available to answer questions and provide assistance.

The gallery at MSVU is open Tuesday through Saturday from 11am to 3pm, and Thursday from 11am until 5pm. Bellamy and Fauteux will be giving an artist talk within their show this Saturday, July 27 beginning at 1pm. Directions for getting to the gallery are here.

gd2md-html: xyzzy Tue Jul 23 2024