In case you missed it yesterday, part 1 of this special three-part feature answered the question “Who cares about a speed hump?” Read on for part 2, and be sure to come back tomorrow for part 3, “Unsafe by design.”

According to city staff, the speed hump on Otago Drive was built in service of two of Halifax’s strategic priorities. One of these, says an email, “is a SAFE & ACCESSIBLE INTEGRATED MOBILITY NETWORK” per this definition: “A well-maintained network supports all ages and abilities by providing safe, flexible and barrier-free journeys throughout the region.”

There is no evidence you have found that demonstrates how a speed hump helps with any of these goals. You have found evidence that supports narrower streets achieving these goals, or streets with bike lanes achieving these goals, but you can’t find proof that streets with speed humps help achieve the city’s strategic goals.

Two weeks after receiving this email from city staff, you’ll watch a transportation advisory committee meeting that demonstrates just how much of this email is a lie about the reality on the streets of the HRM, but you don’t know this yet. Instead, you let your frustration guide you. You send an unprofessional email asking for the evidence to support that statement, as you can’t find any. “Staff aren’t available for an interview and they have provided the info they have available to answer the questions you’ve outlined in your emails,” writes a comms staff supervisor.

The second strategic priority the Otago Drive speed hump addresses, as city staff writes, is “TRANSPORTATION CAPITAL ASSET RENEWAL which includes defining levels of service for transportation related assets (e.g. streets, sidewalks, walkways, etc.) and identifies funding requirements to maintain assets at an acceptable level.” And according to the city’s Pavement Quality Index, this priority will eventually bankrupt the city.

You tend to cultivate friendships with lawyers and mathematicians. You are fascinated by their access to worlds of information locked behind a language you don’t understand. You try not to pester them with minor flights of fancy, just the major ones.

One of your mathematician friends is your favourite to talk to. He doesn’t seem to mind the emotions that often bleed into your debates, ignoring the torrent for the argument beneath. You like the way he challenges your ideas. You’ve known him for almost 10 years and you consider him to be one of your closest friends. Even though you now know his real name, you still don't use it. Just his username. You’ve never seen his face. For a moment you’re distracted from municipal budget documents as you ponder the absurdity of human existence in the modern world.

In the year 2000, the transportation department’s primary concern was the “orderly flow of traffic on an ongoing basis.” By 2003 that had evolved into developing “fiscally sustainable strategies to improve the capacity of the existing transportation system.” Twenty years removed from 2003, the failure to meet this goal is laid bare as every year transportation director Brad Anguish begs council for money to stave off the demise of the deteriorating automotive infrastructure under his purview. Every year since about 2012, city budget documents tout some version of the line that the city is “making considerable progress in the area of infrastructure planning.”

Yet every year, as the city completes its prophetic budget rituals, Brad Anguish is dragged in front of council to be tormented by the city’s subservience to the automobile. The slow and plodding collapse of his municipal department is visible on the horizon, revealed in the complex hieroglyphics of the “actual spending” columns on the “net expenditures by business unit” spreadsheets. You know they can be understood through the Rosetta Stone of Pavement Quality Index, if only you understood the language of probability. You’ll need to ask your friend for help translating. But first you need some data.

In budget documents, the Halifax Regional Municipality lists its roadways as an asset class. An asset, in fiscal terms, is usually defined as anything that produces something of economic value. An asset class is a group of things that all produce economic value in similar ways. There is no evidence to suggest that automotive infrastructure is an asset.

A liability, in fiscal terms, is usually defined as a financial obligation not yet completed or paid for. Your mother was an accountant who kept the books of a company that ran auto auctions. She taught you to recognize how the automotive industry makes its money. They capitalize on people who invest in liabilities as if they were assets. You think you start to understand why car companies spend so much money on marketing.

You’re bored as you compile this data. You imagine your mother scolding chief financial officer Jerry Blackwood for allowing Brad Anguish to get away with this. It makes you uncomfortable to realize you are following these people’s careers like they kick a ball for a privately owned sports team in Bristol City. Why is it weird to care more about the careers of public servants than professional athletes? What would the action shot look like on the front of a CFO trading card anyway? Data entry remains painfully boring. Your finger starts cramping as you scroll badly scanned budget documents reincarnated into unholy, unindexed PDFs. You wonder why it's weird to follow the career of a man who controls your city's purse strings, but far more acceptable to know every detail of a man who kicks a ball. You notice old city documents sometimes use Comic Sans.

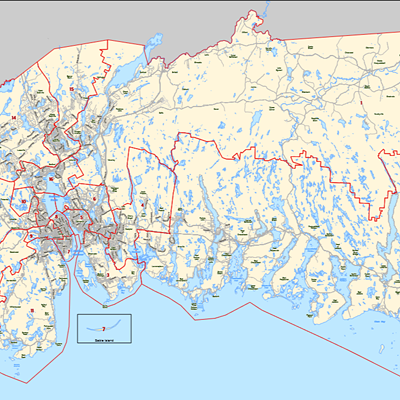

Compiling 20 years of road spending data, you realize that the ability to move people around is an asset. The land under roads is an asset. What turns roads into a liability is the strategic priority of TRANSPORTATION CAPITAL ASSET RENEWAL. Over the past 20 years the city has spent more than half a billion on its roads. The cost goes up by about a million dollars each year, while the quality goes down. Converting municipal pavement data to letter grades, in 20 years our road network has gone from a B+ to a D for a nice cool $537,260,384 of wasteful public spending.

You have identified one of two bureaucratic processes that are responsible for structurally undermining council’s long-term goals of road safety and adapting to the ongoing climate emergency. You find it funny (not ha ha funny) that you’ve made this realization after sitting in congestion for 20 minutes in a two-lane Tim Hortons drive-through making yourself late to a five-year-old’s hockey practice. You find it funny (not ha ha) that drive-throughs still exist five years after the council declared a climate emergency. You shouldn’t be surprised now that you have 20 years of data outlining the scope of political failure. You are anyways.

Even though we are taxed for road safety, and taxed so we can have freedom of movement throughout the city, the city is not careful with those tax dollars. They are happy to take that money and waste it on automotive infrastructure, in spite of a mountain of evidence that suggests that spending is working to undermine Halifax’s stated long-term strategic goals.

You have been watching council for almost five years now. Cathie O’Toole's comments are the first time you remember hearing someone in power talk about being responsible with tax money. It should be a moment of optimism, instead it fills you with dread. She is saying this to warn against evidence-based spending. Not because she thinks the money would be wasted on a sobering center, but instead because in spite of evidence and best intentions, money earmarked too early will end up being squandered by wasteful, inflexible, bureaucratic processes.

No such careful consideration is given to the money dumped onto our roads. The city demonstrates no fiscal restraint when squandering public money on liabilities that kill and disfigure us while destroying your spaceship’s life support systems.

You start to feel betrayed by your municipal government. The slow, cold rage of living through the systemic betrayal of good governance starts to take root.

You think it might be best to do your job virtually for a while.

With files from Martin Bauman

In part 3 of “The saga of Otago Drive,” we cool off with a nighttime ride through the city of Dartmouth and its neglected neighbour, the grouping of houses, parking lots and drive-throughs that we call Cole Harbour. It also has a solution to our woes, but you’ll have to slow the blazes down and wait for tomorrow.

Editor's note: Want more stories like this? Paying Coast Insider members help us produce great journalism. Support The Coast for as low at $1.90 per week, and you'll also receive Matt Stickland's weekly City Hall newsletter, an exclusive bonus to Insiders. Join us, make a difference and become a Coast Insider member today.