Robin Stewart doesn’t want to raise rents on his north-end properties, but he says city hall is leaving him little choice if it takes away street parking.

The “Haliflats” landlord has been one of the loudest critics of HRM’s proposal to create a new north-end bikeway, which will have the potential side effect of reducing on-street parking along residential streets like Creighton or Maynard.

Stewart, also a member of the Investment Property Owners Association of Nova Scotia, has fought the proposed parking loss with an online petition and multiple emails to media outlets, neighbours, businesses and his tenants.

“The north end is fractured because of HRMs agenda,” he tells The Coast.

But Halifax’s bikeway proposal is far from set in stone, and at least two years away from actually being installed. Maybe longer, depending on the city’s budget priorities. Along with the bus lane on Gottingen, though, the bike network has become part of a wider battle between a contingent of Halifax residents upset about the loss of parking and the municipality’s complete streets strategy.

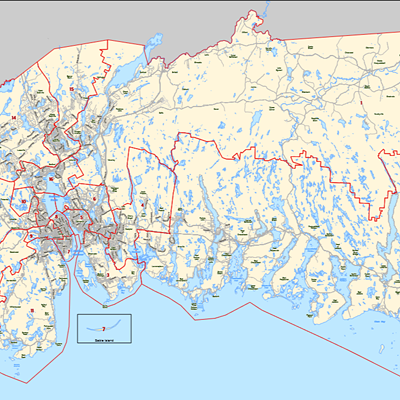

A big part of that plan is a bikeway network in the north end, running north to south between Bloomfield and Cogswell Street. City hall recently completed public feedback on the project’s three potential designs. The first converts Creighton and Northwood to two-way streets, with a 25

David MacIsaac, HRM’s active transportation supervisor, says all three of the designs are in early planning stages. Staff are now reviewing the public’s feedback and will report to

What then, for Stewart's tenants? His buildings have no driveways or dedicated parking spaces, says the landlord.

“Always the parking question,” says Sarah Manchon, chair of the Halifax Cycling Coalition. She’s used to hearing this sort of pushback. It’s hard for the public to understand every impact that a change in street design will have on their

“It's the first tangible thing people will notice, so it's the first thing people will react to,” she says of the parking question. “I don't mind it too much because it does engage people in the conversation and people who actually are interested in the design will become part of the conversation after the first reaction...People don't feel that street design affects their life very much, but it really does.”

“It happens on most projects that we're planning,” agrees MacIsaac. “We understand that it's a factor and at this stage of the game, we're just trying to be as transparent as possible and letting folks know what the parking impacts could be and hearing what they have to say.”

Increasingly, though, the city has been on the defensive about the removal of parking spaces in the north end—ever since a new dedicated bus lane was installed on Gottingen back in October. A video released last month by HRM and Planifax quaintly positions the change as a much-needed facelift for making corridor better for buses, cars and pedestrians.

“Overall a lot of misconceptions have been going around about the project,” says the video's narrator. “Things like there’ll be no parking ever on the street, loading won’t be permitted and even that buses will just be zooming down Gottingen. But this isn’t the case.”

The bus lane did take away some parking by creating a no-stopping zone during peak hours, and Global News has been documenting the near-daily towing of parked cars ever since.

Once the city’s Moving Forward Together Plan is fully implemented, 90 buses will travel down Gottingen in that lane every hour during peak times in the morning and afternoon. Six of those 90 buses will be routes that don’t stop on Gottingen.

The North End Business Association has protested the increased bus presence and asked city hall to change course, diverting many of those routes to Barrington Street instead. But a report last week from transit staff concluded buses wouldn’t be safely able to turn from Barrington onto the Macdonald Bridge without either aggressively tying up traffic or costing HRM hundreds of thousands of dollars in roadway redesigns.

Despite the setback, the

“The speed and volume of traffic

Manchon hopes residents in the north end can see past their weariness of losing parking spaces, to the positive impact these new, living street designs can create.

“It is about choosing some priorities, but it's not about eliminating an entire use of the space,” she says. “It's about making different choices.”