David Robinson is the executive director of the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT), a group that advocates for more than 70,000 teachers, librarians, researchers and other academic staff at 125 universities and colleges across Canada, including academic workers at Halifax’s six universities. The CAUT is a defender of academic freedom and investigates instances of said freedom being threatened on campus.

In February, Robinson spoke with the magazine University Affairs about what defines academic freedom and how tensions over Israel-Hamas playing out on university campuses have led to threats or perceived threats to this guiding principle of academia.

On Wednesday, Robinson joined The Coast for a conversation about the intersection of academic freedom, free speech and violations of university codes of conduct, in light of the recently released report from Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) into whether students’ violated their code in October 2023 when they signed a student letter that was labelled as antisemitism by the school. Read the full report here.

The Coast has covered the Halifax student movement for Palestine, that asks for institutional disclosure and divestment, since May.

The following Q&A with Robinson, which has been edited for length and clarity, includes topics such as understanding how accusations of hate speech and code of conduct violations come up against the principles that public universities are meant to uphold. Robinson told University Affairs that for faculty, academic freedom includes the freedom to teach, engage in classroom discussion, choose how and what they teach, how they grade, how and what they research…and importantly includes the freedom to engage, whether in service of the institution or in “extramural” academic freedom, which can happen in public commentary spaces. He has called this last point “the weak link” of academic freedom. The CAUT has made recent statements in April and May on academic freedom for faculty in times of conflict, and students’ right to peacefully protest and their charter right to free expression.

The Coast: Where does academic freedom for faculty, and the right to free expression that all students have, come into conflict with school codes of conduct or workplace policies?

David Robinson: I think the TMU report is a good place to start. There, I thought the university acted improperly and rushed to judgment early on and kicked it to an external investigation to legitimize what they were doing.

I was wrong, thankfully, and I think the report is pretty good. It makes the case that when you talk about, say, accusations of antisemitism, you have to look at the context in which speech is being made. [TMU’s external investigator] J. Michael MacDonald went through a lot of analysis to land on a definition of antisemitism that I think most people would agree with, although I know it’s still contested.

What we’ve seen in many cases are very clumsy uses of words like hate speech, antisemitism and anti-Palestinian racism without people defining what that is.

What is hateful speech?

Well, there’s a legal definition of it and the bar is set pretty high.

Is hateful speech different from harmful speech?

There’s a lack of clarity around this distinction. Our [teacher] associations are often struggling in response to what administrations are doing when they’re using university policies, I would argue, in loose ways.

At TMU for example, MacDonald found that the application of the Student Code of Conduct was inappropriate and that students hadn’t violated it. But there was not even any attempt by the university to talk to students before accusing them of being antisemitic or of signing an antisemitic letter. And that accusation, when it’s out there, did cause real harm to students who, the report details, were mostly minority students, mostly women, whose careers may be irrevocably and irretrievably lost because of this accusation.

And his report didn’t settle matters because once it was released, it was condemned by those saying he ignored antisemitism.

Which parts of the code were students being accused of violating?

That’s part of the problem we’re seeing. When you start off with very loose definitions or thresholds of what constitutes, say, hateful speech, then what happens is administrators start looking through various school policies and saying, “Where does this fit?” and you start running into situations where you apply codes that aren’t relevant.

This is not just with students. I've had cases of faculty members who've been accused of violating their respectful workplace policy for retweeting something that somebody found offensive about the Israel-Gaza conflict. But, who makes that judgment?

People on various sides of this issue are going to look at various content and feel hurt, or feel upset about something. But does that rise to the level of hateful speech? And is that subjective feeling how we're going to interrogate any possible infractions of respectful workplace policies or harassment codes, or safe learning environment policies?

I think it's no surprise given the power imbalance that almost all the incidents that we're dealing with [at CAUT], deal with people who are engaging in speech that's supportive of Palestinian rights.

Tell us about experiences you've had speaking with faculty and staff within the Halifax university community.

You know, it's been fairly quiet here until recently.

The Dalhousie Faculty Association held a meeting recently and passed three motions that were highly contentious amongst their membership.

These motions were not just calling for a ceasefire, but also calling for divestment, for supporting some of the student protesters–even dancing with the issue of a possible academic boycott–which are all very highly contentious within members, I have no doubt.

But oddly enough, I haven't heard of any cases. Not that there aren’t any, but none have been brought to my attention by any faculty member on whatever side of the issue.

What triggers either an internal or external investigation into accusations of hate speech or code and policy violations at a university?

It's almost entirely at the discretion of the administration, following a complaint.

If someone complains that a colleague retweeted a harmful or hurtful cartoon about the situation in the Middle East, the university can decide whether there’s merit to it, or whether they want to immediately start an investigation.

I think what we're seeing right now is that, because this is such a hot potato issue, a lot of universities are immediately starting an investigation because it takes the heat off.

And who initiates an internal investigation?

It depends on the nature of the complaint. It would start with administration, through the vice-president provost, and oftentimes the Human Rights and Equity Office would be involved in accusations of discriminatory speech or harassment. If it's a violation of a respectful workplace policy, it might go to human resources or the dean…There's a whole administrative machinery that's in place.”

And how do working definitions of discriminatory speech or harassment relate to individual school codes of conduct and workplace policies?

That's where it gets complicated.

Remember, an allegation is an allegation. But, the outcome is what helps us better define what might or might not constitute antisemitic speech.

There are some people who feel very strongly, for instance, that the call for a free Palestine is antisemitic, because in some ways, the speaker, so it's alleged, is calling for the destruction of the state of Israel and Jewish people.

I understand where that comes from, but I think the context in which the speech is made and the intent, as the MacDonald report pointed out, also matters.

Terms can be ambiguous, and you have to be careful about rushing to judgment. I think the problem is universities not having clear definitions.

I think most universities in Halifax defer to Nova Scotia’s Equity and Anti-Racism Strategy for definitions of discrimination, including antisemitism.

Yes, and human rights codes, essentially, say it’s illegal to discriminate on the basis of “blank.” Antisemitism is often captured in terms of ethnic origin or religion. So, if you refuse to admit Jewish students into a university, that’s clearly antisemitic and clearly contrary to the code. Where it becomes trickier is the way that gets grafted on to other university policies, like respectful workplace, civility policies, or safe learning spaces.

In principle, I think that sounds fine because these policies are an exhortation for us to be nice to each other. However, in practice, those policies are a bit cumbersome in terms of how they're employed. Because they are relatively vague and ambiguous, it gives administrations enormous amounts of discretionary authority to decide when or when not to employ them.

What we often find is that the use of civility or respectful workplace policies are essentially ways of targeting people who are the gadflies, the outsiders, or those that other people find annoying. But I don't think it rises to the level, necessarily, of harassment or discrimination under the law.

What happens when a student makes a complaint about a faculty member?

If a student comes to an administrator and says, “something a professor said in the classroom has really hurt me and I don't feel safe in that classroom anymore,” that administration—largely because of the growth of this client-service model—is very happy to try and resolve the issue by having an investigation or looking at what policy that they can employ.

We have a lot of these kinds of investigations now which don’t rise to the level of a violation of policy, but in the interim, you put a cloud of suspicion over a faculty member. It really puts everything on hold.

I’m not trying to minimize legitimate complaints—there are legitimate complaints where some of our members do behave badly and they have to be held to account—but I think there’s been a slide into a subjective notion of harm coupled with a drive to keep the student-customers happy that’s led to, from what I’ve heard from members, a proliferation of complaints and investigations.

In talking about students as consumers and clients, you’re referencing changes to the funding of public universities which are now largely funded privately through tuition money, yes?

Yes, and that's a really important point because, particularly in light of the student encampments, institutions now see themselves as privately run organizations who then are asserting private property rights as a justification for why they don't have to live up to principles of free expression or peaceful assembly.

In these cases the universities would argue that they’re not a public space.

This isn't new, but it takes on increased resonance with the increasing, as you said, privatization of these institutions where now I think every province, with the exception of Newfoundland and maybe Quebec, see the majority of revenues for universities and colleges not coming from public sources but from private sources in the form of tuition fees. So, we have a largely privately financed system now.

What we're seeing as a corollary of that is this reliance on private property rights, in the injunctions that various institutions like McGill, UofT and UWaterloo have sought, where they assert that the university is not a public space, it's a private space, and therefore they have authority to regulate their own private property as best they see fit.

And those principles of free expression and peaceful assembly, as articulated in the Charter of Canadian Rights and Freedoms, don't apply because they’re private spaces—they’re not government and they’re not public.

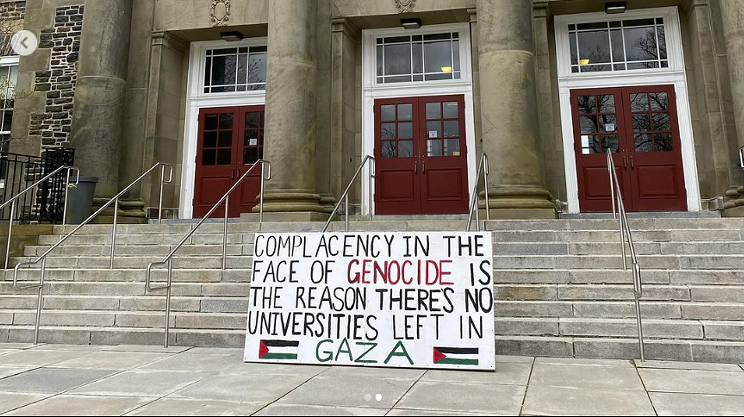

While thinking about the student encampment at Dal—which involves students from five Halifax universities—what should we expect from these institutions which are still considered public?

First, framing this as private space is a profound dereliction of responsibility and duty and an understanding of what universities and colleges really are. I'm shocked to see senior administrators assert this. Almost all institutions are created by provincial government acts—they’re creatures of legislature.

They're given land space for a specific purpose, and what is that purpose? To engage in intellectual debate and discussion.

The actual purpose of the property on which the university sits is to encourage freedom of expression and academic freedom, which includes peaceful assembly. There’s been a long history of students engaging in demonstrations at universities. This is only the latest iteration of it.

And finally, what supports are there for faculty and/or students who might feel their rights to academic freedom or freedom of expression are being threatened on campus?

Unfortunately for students, it's much easier for faculty to find reassurance of their rights within their own faculty associations. They’re unionized members with a collective agreement which provides guarantees of academic freedom in teaching and research and an extramural expression, which means expression on the public affairs of the day.

For students, I think it became clear particularly in the TMU just how vulnerable they are. There is no equivalent body for them to go to to assert their rights. Fortunately, a number of faculty members in the law school came forward and gave them advice and helped guide them through the process. But they couldn't hire their own lawyers. They couldn't get their own independent legal advice without these other resources for advice. So, students are particularly vulnerable.

And this is the contradiction: we have institutions talk about how they care about students, how they want to create a safe space for students, but then they treat some students absolutely miserably as we saw in the TMU case.

That was the biggest disappointment in the report that followed. MacDonald eviscerated the administration and called them out for engaging in the same kind of behaviour that they were accusing the students of which made me think he would have recommended that there be an apology to the students…and there wasn't. The administration could have said ‘We rushed to judgment, we made a mistake. We're sorry,’ and have that on the record. But the administration has been silent. I guess the sad news is that for students, even when you're exonerated, you don't get an apology.