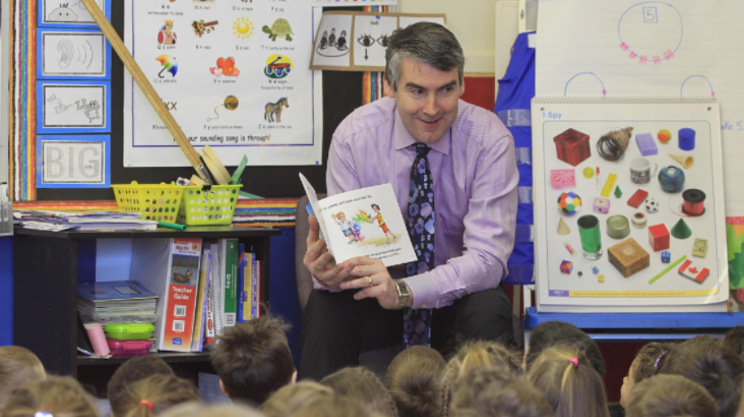

On Monday morning a recalled Nova Scotia legislature will begin the first steps to forcing a new collective agreement on teachers and taking away their right to strike. At the same time, outside Province House, angry crowds will join in a protest against the Liberal government’s battle with the Nova Scotia Teachers Union (NSTU).

Sheena Johnson won’t be there. She’ll be driving back from Cape Breton, where the mother-of-five dropped off her kids with their grandmother on Sunday night. It was the only childcare she could think of—and afford—on short notice after Saturday’s surprise announcement that Nova Scotia’s public schools will be closed until further notice.

“I’ve never been that far away from them for that long,” says Johnson. “[The province] could have at least gave a warning, like a legit warning, and accommodate with childcare. Childcare costs a lot.”

The province says it needed to close Nova Scotia’s schools because the NSTU’s planned work-to-rule actions would create an unsafe environment for children. But making that call with only 36 hours notice (and no certainty when schools will reopen) has left parents to pick up the pieces and separated Johnson from her kids just in time for the holidays.

Johnson moved to Dartmouth from the Mi’kmaq community of Eskasoni back in September. She’s a student in the Nova Scotia Community College’s metal fabrication program—one of 20 First Nations tradespeople selected for a pilot project to increase diversity at the Irving Shipyards. The classes take up most of her day. Student assistance and family benefits cover her monthly expenses, but just barely.

“I don’t really know anyone around here, so I can’t really just say, ‘Hey, watch my kids,’” she says. “I have to be in class. If I miss a day it’s $60 off my student assistance. As small as it is, I need every bit, as much as I can.”

Every weekday Johnson says she gets up and drops her four oldest kids off at school before driving over the bridge to drop her three-year-old at daycare on Gottingen Street. Then she goes back over the bridge to get to class at NSCC’s Akerley campus. She pays for a sitter after school—at $30 a day—until she’s done her classes, then does two more trips across the bridge to pick up all her kids, go home and make supper.

“It comes to about $1,000 even, getting my kids where they have to go, so I can go to school,” she says about her monthly childcare costs.

When she heard the schools were closing, Johnson says she posted in babysitter groups looking for professionals to look after her kids but they were all either booked or charged more than she could afford. Like other parents on social assistance who are without any ability to take time off, that left her with few options.

“The government’s actions in locking out students is an attack on the poorest resourced families and communities,” writes El Jones on Facebook. The activist and Halifax Examiner contributor spent her Sunday with other leaders in the African Nova Scotian community organizing tentative plans for a community-run school to replace shut-down public classrooms.

“They know poor people can't afford last-minute childcare. Jobs that already underpay and exploit workers won't give time off to parents,” writes Jones. “It's right before Christmas and families are now expected to find resources for childcare at a time when finances are already tight...Make no mistake, this isn't just an attack on teachers, it's an attack on the most vulnerable families and children in our society.”

The proposed work-to-rule action by NSTU members would have limited teachers to the explicit duties spelled out in their contract, including arriving 20 minutes before classes and leaving 20 minutes after. That lack of supervision—particularly during lunch—would have created an “unsafe” environment for children, according to the province's school boards.

“I am receiving many inquiries from parents,“ writes a member of the Halifax Regional School Board to the department of Education and Early Childhood Development. “Most relate to the safety of their child(ren) and are looking for assurance of a continued safe and positive school environment. At present, under current conditions as described by the NSTU, I do not believe that to be possible.”

Education minister Karen Casey said the school closure is a short-term and necessary inconvenience. Nova Scotia’s Education Act guarantees a safe and productive learning environment, and the minister says ensuring that supersedes any labour negotiations.

“More than 43,000 students are supervised at lunch and at other times by teachers,” Casey said Saturday. “These students could be left unsupervised in classrooms or on playgrounds and that is unacceptable.”

The NSTU disputes those claims.

“If Minister Casey was concerned about the safety of students, she would have let them go to school next week,” writes NSTU president Liette Doucet in a press release. “With this step our government is showing that it will do anything except negotiate with teachers.”

Johnson wasn’t worried about work-to-rule, “as long as the kids are learning and doing their tests and studies.” The province going nuclear to prevent kids from unsupervised play is another story. That has a severe effects on families, especially for those already just scraping by.

Some community centres like the Dartmouth Sportsplex are offering day camps for kids, but without knowing when classes will resume, Johnson chose to bring her kids back to Cape Breton. She says they’ll attend the non-unionized Eskasoni Elementary and Middle School until classes in HRM re-open, or until her holiday break at NSCC starts on December 15 and she can join them. Her three-year-old will remain with her in Halifax.

Schools in Nova Scotia could open as early as Friday, depending on how much opposition the proposed Teachers’ Professional Agreement Act faces. For many parents, that’s not soon enough.

“Let the kids go back to school,” Johnson says, “or at least accommodate the childcare situation.”