Just two months after being granted approval to commence deepwater exploratory drilling, the BP Canada oil platform sitting 300 kilometres offshore sprung a leak last Friday.

Quickly, 136,000 litres of toxic “drilling mud” spewed into the ocean from a pipe 30 metres below sea level. For the time being, both the leak and the drilling have stopped. BP won’t be able to resume until the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board finishes its investigation into what went wrong.

The mechanical failure is exactly what environmental advocates and local fishers feared would happen when the CNSOPB granted BP Canada approval to start drilling back in April—after the company had already begun moving its West Aquarius platform to Nova Scotia’s waters.

Critics of the board—most vocally environmentalists and fishermen—say the regulatory body is too closely connected with the oil and gas industry. That it has a conflicting mandate to both promote and monitor the

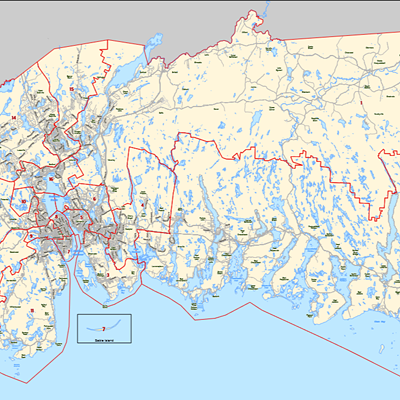

The Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board oversees an “

In 1984 the Supreme Court of Canada decided Newfoundland had no jurisdiction over the continental shelf. This ruling remains significant to Nova Scotia today. In 1990 it spawned the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board: A handful of people appointed by the federal and provincial governments to regulate petroleum activities in the Nova Scotia offshore area.

They’re the ones—currently Keith MacLeod, Paul Taylor, Roger Percy, Harold Giddens, Corrina Bryson and Barbara Pike—who issue licenses to companies like BP for offshore exploration and development.

The industry connections among those members are clear enough. Every member of the Board has had a storied career in the field of oil and gas exploration, in one capacity or another.

“Barbara Pike is the former head of the Maritimes Energy Association, where she promoted offshore oil and gas as well as fracking,” says Gretchen Fitzgerald, national program director with the Sierra Club.

This criticism was echoed in a 2016 report from a federal Expert Panel—comprised of a scientist, an environmental consultant, an Indigenous lawyer and an environmental lawyer—that reviewed environmental assessment processes across Canada. It noted public concerns that petroleum boards’ close relationships with those they regulate

Critics have noted that board members’ backgrounds and ongoing close connections with the oil and gas industry point to a more fundamental problem and a too-familiar story: A high-impact industry that essentially regulates itself.

Sadie Toulany, a spokesperson for the CNSOPB, sees no conflict. “It is the role of governments to promote industrial activity in the Canada-Nova Scotia offshore area,” she says. “Our job is to ensure regulatory compliance.”

But others, including the federal government’s expert panel, have noted that petroleum boards have two conflicting mandates: To protect the marine environment and to promote resource extraction. That conflict of interest, real or perceived, is

“They are basically promoting these resources at the same time they are supposed to be regulating,” says John Davis of the Clean Ocean Action Committee, a consortium of fishermen’s organizations and fish-plant workers.

Davis says the CNSOPB has largely ignored his 9,000 members, all of whom rely on the offshore area for their jobs.

Toulany insists the board works to include stakeholders in the decision-making process when developing industry guidelines, conducting environmental assessments or making regulatory decisions. She says a Fisheries Advisory Committee meets quarterly and includes people from fishing groups, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Natural Resources Canada and Nova Scotia’s Departments of Agriculture and Fisheries and Aquaculture as well as Energy.

“Members provide advice and suggestions,” she says, “in work authorization applications, regulations and guidelines. Our team of environmental professionals draw on the knowledge and experience of experts from other government agencies, such as DFO, to ensure that risks to the environment are properly assessed and that they will be appropriately mitigated.”

John Davis counters that his members have not been given a chance to give input into the approval of exploration and drilling licenses, neither by the board nor by government authorities such as the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency.

“In the BP issue,” he says, “the environmental assessment process was carried out without public hearings. Fishermen would have to write a brief to the CEAA, which is completely out of touch with the promises the federal government made about

As inscrutable as the CNSOPB may seem now, under the Trudeau government’s proposed Impact Assessment Act (part of omnibus Bill C-69), next year it will gain much more power and direct involvement in the environmental assessment process, which is currently managed by CEAA, with final decisions made by the minister of Environment. The new legislation would require an opportunity for direct input from and cooperation with the petroleum boards.

The problem with that, again according to the federal expert panel review, is that petroleum boards lack expertise in planning for environmental impact assessment. They are oil managers, with backgrounds in the oil industry, not biologists or oceanographers.

Also, as Gretchen Fitzgerald puts it, “They have a tendency to ignore the bigger environmental picture while promoting

Once again, this proposed change runs counter to the findings of the federal expert panel, which recommended a separate, independent body making decisions on environmental assessments. It isn’t hard to see the danger of having the same group of people, with oil and gas backgrounds, assess, decide on and regulate drilling projects offshore.

Fitzgerald questions the need to have offshore Boards at all. “Why do we give so much control to these Boards with small staff and membership when we have governments with those responsibilities?”

She would like to see the formation of an arms-length, tripartite (federal, provincial and Indigenous) decision-making body.

“The new Impact Assessment Act could be a mechanism of that. If you want to have a legitimate process it needs to be done right, with climate and environmental goals incorporated from the beginning.”

Lisa Mitchell of East Coast Environmental Law worries we’re sacrificing credibility for the sake of the board members’ technical expertise.

“I like the idea of an independent review panel,” she says. “It’s a positive step, but you shouldn’t have the regulator sitting on the panel. The technical expertise is imperative to the process but they shouldn’t have that much influence. They are promoters of the oil and gas industry.”

John Davis points to Norway’s offshore system as a better example of both environmental protection and economic management.

“All areas of Norway’s offshore are closed to oil and gas until they can prove they can work safely and protect the rights of other stakeholders,” he says. “In Nova