Tonight, activists, politicians and community members from across Nova Scotia will meet at the Halifax Central Library for Connecting the Dots: Confronting Environmental Racism in Nova Scotia. The free event, organized by ENRICH (Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequalities & Community Health Project), the Nova Scotia Public Interest Research Group and the Ecology Action Centre, aims to create more awareness of environmental racism happening in Nova Scotia. Ingrid Waldron, an assistant professor at Dalhousie University and organizer of ENRICH, will be on hand to discuss her research in the disproportionate polluting of low-income minority communities. Waldron took some time to chat with The Coast about tonight’s event.

What’s going to happen at the panel discussion tonight?

I think I’m not going to focus too much on the specific findings, but what I'm going to begin with is an overview of my project that I started in 2012 on environmental racism. So, I'm just going to provide the stages, and the activities that we've engaged in to mobilize communities on the particular issues.

Then the central aspect of the event would be the panel—which is being moderated by Lynn Jones—will include community members from the Mi'kmaq and African-Nova Scotian communities. They're community activists, so they're going to talk about some of the challenges, successes they've had mobilizing community members in their regions around environmental racism. We're going to have Lenore Zann (NDP MLA for Truro-Bible Hill-Salmon River-Millbrook) on the panel. I collaborated with her earlier this year on the first ever environmental racism bill in Canada (Bill 111). She's going to talk about that bill and what she thinks government needs to do to address the issue. And we have Carolann Wright-Parks, who's from the Greater Halifax Partnership. So it's really a panel to discuss what they've been doing and how environmental racism manifests in the province.

Can you talk a bit about your research?

I started a project in 2012, I started building a team of community members from the M’ikmaq and African-Nova Scotian communities, government and activist professionals to discuss how we could address environmental racism across the province. Since 2012, I've held workshops in those communities, met with residents and discussed some of the issues around environmental racism. Particularly the health effects—people talked about higher rates of cancer in their community, in their family, they talked about asthma, they talked about learning disabilities. These are some of the illnesses that they believe are outcomes in living close to polluting industries and other environmental hazards.

What are some of the worst examples you’ve seen here?

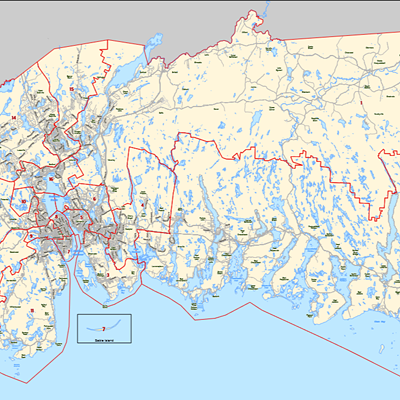

I think Boat Harbour's pretty bad. That's been an issue since the late 1960s. They've been trying to mobilize communities around that issue for quite a while. Certainly the Minister of Environment took some steps last year to deal with that and that got a lot of news. The landfill in Lincolnville is also a pretty serious example. There was a first-generation landfill throughout the 1970s and beyond. It was closed in around 2009, but then they opened the second-generation. So the community's concerned about water contamination, of course. They talked about higher cancer in their community as well. Those are the two most visible examples.

Halifax has a notable former example of this phenomenon, in Africville. But this isn’t a problem limited to Nova Scotia. Have we addressed any of these problems effectively in the past? Is Nova Scotia better or worse than other places in handling environmental racism?

That's a difficult question. I think, because in Canada there's a hesitance to even talk about race and racism, it's asking people to take a leap then to kind of talk about environmental racism. This is a term that people in the United States have been familiar with for some time. Communities generally in the United States have taken steps to address it, but not with a lot of success. I think this is a new term in Canada, and I would say in general government has not addressed it successfully.

Communities have been kind of mobilizing on this issue for a while, if you think of the Idle No More movement, of indigenous people, that's a prime example of communities that have been trying to address the issue. So, no, as long as government doesn't understand the link between the environmental justice issues communities are facing and racism—how it manifests in the province and the fact that environmental racism is one manifestation of structural racism in Canada, just like unemployment, under-education, just like segregated schools in Nova Scotia—I think if they don't have that critical understanding of it, the move to address it will be slow.

”That's how racism and race manifests in very subtle ways. It's not about saying people are necessarily, purposefully thinking about harming people. I think it's much more subtle than that. It's about which communities you value and which communities you don't.”

Environmental racism, as a term, brings “race” really to the forefront. You’ve pointed out social class is also a big motivating factor. Why can’t we overlook the race issue?

That's an argument that has been brought up. Environmental racism is about disproportionate location of polluting industries in communities of colour and the working poor. But it's also about the lack of voice, the lack of power these communities have in decision making. When I argue it's an intersection between race and class, some people might argue, “No, I just see the class. I don't see the race.”

There's often one example I give, which is Sackville, which is a low-income white community, and which had their issue [the Sackville Landfill] to some extent addressed in 2009, the same time as Lincolnville. Sackville was able to get their issue addressed and receive compensation. Lincolnville is still waiting for that, and happens to be a black, lower-income community. That's one example I often give about the issue of class. You have two low-income communities, one white and one black, however the white community was able to get their issue addressed—perhaps not quickly but certainly significantly faster than African-Nova Scotians in Lincolnville.

I think it's important to understand the intersecting of these two things, when you have low-income individuals and individuals who are racialized or of colour, you've got a double whammy. Two factors that actually serve to marginalize that community and serve to disempower that community even further. In terms of who gets heard, and who is actually running the show at government, if you look at the faces of government officials, they're white. Not all of them have a critical understanding of racism. Not all of them have an understanding of these communities. It's also about who's running the show and the kinds of policies and decisions they're making; that they're making through their eyes that often don't take into account the experiences of other community members whose experiences they don't share. That's how racism and race manifests in very subtle ways. It's not about saying people are necessarily, purposefully thinking about harming people. I think it's much more subtle than that. It's about which communities you value and which communities you don't. If we're going to be honest, many people don't value people who are lower-income, who are poor in our country, and furthermore those who are raced in a particular way. It's much easier to place an industry there because nobody is thinking about them.

Recently we’ve seen a proposed waste-processing facility in Lake Echo and a planned asphalt plant in St. Margaret’s Bay face opposition from those community and receive swift political action.

It's a perfect example. Environmental racism isn't about specific instances of polluting industries and communities, it's about a pattern. When you look overall, there's a tendency to place them in certain communities. When you look overall, those communities of colour don't seem to have a voice. Their concerns don't get attention. I might get somebody from a white, low-income community, say “I'm dealing with this issue as well.” Environmental racism is very specific. It's about a pattern, a trend. That's the way people really need to view the problem.

Is an overall political policy more effective than piecemeal solutions of organizing against individual cases?

That's what the Bill was actually doing. It wasn't looking at specific communities, it actually requires a committee of government officials to come together, consult with communities—Acadian communities as well, which are white communities—M’ikmaq, African-Nova Scotian communities; there's a generalized approach to this bill, which is just the first step. I do think, yes, a policy that addresses environmental racism in Nova Scotia and in Canada, is the best way to go instead of looking specifically at different issues. However, I still think, when you have serious issues like Boat Harbour, and Lincolnville, there needs to be a move on those at the outset. You can still develop a policy in general and still address those issues. I think you can do both at the same time.

Aside from attending tonight, how can people get involved in fighting against environmental racism?

I have a website, called ENRICH. There's also a Facebook page. They can contact me through my Dalhousie email, which is on the Facebook page. Those are the three main ways. They can also leave their name, if they wanted to. There's going to be a sign-up sheet at the event for projects if they want to get involved later.

Connection the Dots: Confronting Environmental Racism in Nova Scotia

Tuesday, July 28, 6-8:45pm

Halifax Central Library, Paul O’Regan Hall