David Clark remembers where he was the day the trouble started. He was walking through the woods on his property in Melrose, a small community on the St. Mary’s River, a two-and-a-half-hour drive east of Halifax. Sun shone through the trees. Beams of light landed on the small brook. The rolling water sparkled. It added a spritz of freshness to the air. As he walked, leaves crunched. He noticed a figure down by the brook. The man wore blue jeans and workboots. Clean-shaven, tall and lean, he looked to David like he was used to physical work. David asked him what he was doing. “I’m a prospector,” the man told him. He pointed to a dip in the brook. It was a spot gold miners had altered decades ago, he said, to help process gold. A conversation followed.

David quickly learned that in Nova Scotia anybody could stake land for mining, claiming the “mineral rights” to whatever might be in the ground, even if somebody else owned the property and lived on top of it. If a mineral like gypsum or gold was found, the stakeholder would have the right to mine it. If a landowner stood in the way, the matter would go to court.

After the encounter, David was unsettled. He knew there had been historic gold mining in the area. This guy was a modern-day prospector looking for gold.

Straightaway, David staked a claim on his land. He went home feeling secure. He wouldn’t be losing his property anytime soon to some unknown miner.

That was 2010. In 2011, David was unable to renew his claim. He figured it was more trouble than it was worth, and forgot about it.

The next time David and his wife Patricia Clark heard the words “gold mine,” it was an announcement in 2018. A company had plans for a big open-pit mine nearby. Atlantic Gold had already opened a mine in Moose River, halfway to Halifax. Now they were coming to Melrose.

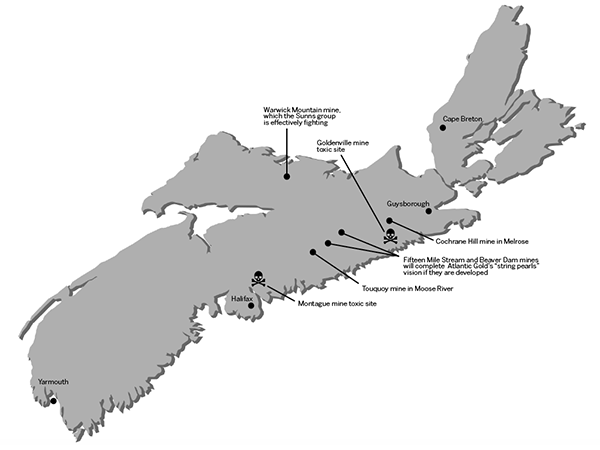

Atlantic Gold is one of several companies digging in for Nova Scotia’s present-day gold rush. It opened the Moose River Complex, with our province’s first-ever open-pit gold mine, called Tuoquoy, almost two years ago. Atlantic Gold boasts “best in sector margin and cash flow generation” due to its “lowest cost” gold production. The Melrose mine is the second of four mines the company wants to open between Halifax and Cape Breton, a project it calls the “string of pearls.”

After Patricia Clark found out about the Melrose mine, she started researching gold mining on the internet and discovered that several gold companies are active in the area—staking land, exploring and proposing projects. She found a map showing gold deposits in the province. It also shows areas staked for mineral exploration. The Clarks’ property is now staked by an exploration company called Meguma Gold.

Meguma is “focused solely on creating exceptional value for our shareholders” according to its website. The company owns claims that cover more than 179,000 hectares of Nova Scotia, equal to a third of PEI’s area. The company staked the land surrounding Atlantic Gold’s claims in Melrose, including the Clarks’. Meguma Gold is named after the Meguma Group, a type of Nova Scotia rock unique in North America. Millions of years ago, when Pangaea split, a small part of Africa fractured away and was dragged west. Nova Scotia’s southern half, a 300-kilometre-long stretch of gold-bearing rock from Yarmouth to Guysborough, is actually a “chip of Africa,” according to the journal Atlantic Geology. It’s the only piece of African landmass in North America. Our gold history thus began in the Triassic Age.

Roughly 175 million years later, in 1860, a farmer from Musquodoboit named John Pulsiver was led by Mi’kmaw guides Joe, James and Francis Paul to a quartz boulder shot through with gold. The Mi’kmaw people knew about gold. They called it “wisosooleawa,” or “brown silver.” There are many stories of settlers being led to gold deposits by Mi’kmaw guides.

Pulsiver registered the find, which kicked off the first Nova Scotia gold rush. Gold was so easily found it could be picked from under rocks in a river; gold panning was probably the first extraction method prospectors used. Then came other tools.

Miners would swing picks all day in the Nova Scotia woods, dripping sweat, covered in biting black flies and mosquitos, cracking rocks. Pieces of rock were crushed and rinsed with mercury to separate the gold. Bigger apparatus soon appeared, like the stamp mill, a giant machine that looks like a pipe organ, designed to crush huge rocks that held tiny specks of gold. These mills did not make the same music as a pipe organ. Large iron rods standing on end would rise a foot and then drop, smashing ore to a fine sand that got sluiced through the mill with water. Anybody working near a stamp mill would hear the constant sound of 2,200 kilograms of iron hitting bedrock, each rod landing once per second. It sounds like the Iron Giant doing Riverdance.

A five-stamp mill could pulverize five tonnes of ore in 24 hours. Nova Scotia had at least one 30-stamp mill. After pounding, the heaps of wet paste would be drenched with mercury or, in later gold rushes, a mixture of cyanide and lime, to separate out the gold. Everything left over, the tailings, was poured into the nearest river or lake. The first gold rush was hasty and ran from 1860 to around 1874. More organized rushes, involving dynamite, bigger machinery and larger companies, occurred from 1896-1903 and 1932-42.

In those early days, nature was endless and threatening. There was little worry about damaging the environment, especially when a life-changing score might be hiding somewhere in the ground. The perpetual flow of sparkling water would carry away the worthless paste, and hopefully a miner would make a few hundred dollars before losing their mind to mercury poisoning, dying of heat stroke or being trapped in a mine collapse. Many of the hopeful miners of the first gold rush had abandoned life on a farm to find riches. All labour was hard in the 1860s; gold mining was gambling with a pickaxe.“If gold was going to make Nova Scotia rich, we would already be a really rich province.”

tweet this

Production ramped up quickly. Soon, people were coming from all over the world to mine. Three years before Pulsiver’s discovery, the government of Nova Scotia had gained full ownership and regulatory authority over all mineral deposits and mining activity in the province.

To organize the gold rush, the government established districts and regulated claims. Sixty-four gold districts were created. Whole communities sprang up around gold-rich areas. Tangier, Waverley and Goldboro were all built around gold mines.

Especially after machinery came into use, gold mining was a wasteful enterprise. Through the first three gold rushes, Nova Scotia produced over 37 tonnes of gold and over 3,000,000 tonnes of tailings. If you put the tailings on a scale, you would need 30,000 blue whales to balance it. As for the gold, one third of one whale would balance.

Goldenville, a 15-minute drive from David and Patricia Clark’s property in Melrose, became by far the most productive gold district in the history of Nova Scotia. More than 200,000 ounces of gold were taken from the land before it shut down toward the end of the third gold rush in 1941. It was closed to the public by the province last fall because the tailings are still too toxic for humans to set foot on.

Linda Campbell’s rubber boot sinks into gray muck. She is stepping through a historic tailings site leftover from the Montague mines, just outside Dartmouth. The site was abandoned about 80 years ago. Along with Goldenville, it was officially closed last fall by the government. Campbell worries that there is no fence to keep people out, and only a few signs to identify the area as a toxic waste dump. She is allowed in as a researcher.

The muck is so thick it threatens to suck the boot off her foot. There is a glossy film on the puddles. “It looks like it’s oil, but it’s not,” says Campbell, “it’s a very specific type of bacteria that is processing this. It lives on the tailings.”

Campbell is a professor and senior research fellow at Saint Mary’s University. She began studying tailings sites in 2013. In the frenzy of the early gold rushes, it was difficult to keep track of everything. Surviving documentation of mining activities, such as the amount of mercury used, is sparse. It concerns Campbell. We don’t know where all the piles of tailings or the abandoned mine shafts are. People may be living on or near piles of old waste. A hiker could stumble down a forgotten mine shaft.

Sites like this have about 340 times the normal level of arsenic, and 140 times the normal level of mercury. Arsenic is a known carcinogen, and mercury is a known neurologic poison.

Some insects breed in lakes. Campbell’s students have found that at tailings sites, insects have 50 times more mercury in their bodies than normal. Those bugs fly around. Some are eaten by fish like salmon. “The toxins tend to bioaccumulate” up through the food chain, says Campbell. That means we might be eating animals with high levels of dangerous elements. One modern method of tailings containment is to build an artificial pond where the tailings are submerged in water, which is held back from spilling onto surrounding lands by a tailings dam. But even if the tailings dam is successful at keeping poison out of wells, insects may be carrying it into the animal population.

The most thorough report on historical tailings published to date was a Natural Resources Canada study of 14 mine sites (out of over 360 in the province) published in 2012. It found that the harmful elements of tailings seem permanent and can easily spread. The report states that “in some areas the tailings have been transported significant distances (>2km) offsite by local streams and rivers.”

The historical tailings site at Montague is a field of gray sand that turns into a cement-like mire when it rains. On a hot day, the tailings become as fine and light as ash. It smells like sand. The ground is drab. Colourless. Motionless. Campbell’s footprints from today might be found months later, almost unchanged. She is hoping research will find a safe way to count and contain these piles of toxic waste.

The provincial government announced July 25 that Nova Scotian citizens will spend $48 million on cleanup of the Montague and Goldenville mine sites. Lands and forestry minister Iain Rankin called them “the two most egregious” sites in the province. There is no plan yet for the other 63 historic mining districts and 360-odd mines.

Though modern practices are much more sophisticated and efficient, what becomes of tailings is perhaps the biggest concern among opponents of the Melrose mine, and in the gold mining industry in general. There is no standardized way to deal with the toxic byproducts of cyanide gold leaching. Tailings dams have to be monitored forever to make sure they don’t leak into the water table. All residents of Melrose live on well water.

Industry website mining.com published a story March 2019 saying, “there are no set of universal rules defining exactly what a tailings dam is, how to build one and how to care for it after it is decommissioned. There are about 3,500 tailings dams around the world…. They are mostly constructed from the waste material left over from mining operations, which—depending on the type of mine—can be toxic. Only three countries in the world ban upstream dams.” Canada is not one of them.

The UN Environmental Programme said in 2017, “although the number of dam failures has declined over many years, the number of serious failures has increased, despite advances in the engineering knowledge that can prevent them.”

In August 2014, a tailings dam breached at the Mount Polley mine in BC and a torrent of toxic water plunged down upon lakes, creeks and rivers. The grey waterfall released by the dam contained 24 million cubic metres of waste and mine water, enough to fill 2,000 Olympic swimming pools. The cleanup is costing citizens $40 million. The provincial government had three years to lay charges but did not. Five years later, an expert panel recommended charges against the company under the federal Fisheries Act. The panel called it a preventable accident. The federal government had until August 4 to lay charges, but did not. The possibility of other charges remains. The tailings released into Quesnel Lake are still sitting at the bottom.“You want to sum it up? Dump trucks, dust, devastation. That’s basically what our life is now.”

tweet this

In January, a leak at the Moose River Complex spilled 380,000 litres of waste. It was safely contained by an artificial pond designed to catch such a spill. The proposed mine in Melrose will be dug on Cochrane Hill. The plan is to create a tailings pond with a 70-metre-high tailings dam on the hill.

It is obvious that Scott Beaver loves the St. Mary’s River. He lives beside it. His house is full of windows that look out over the flowing water. “From the age of five, I lived here,” he says. He spent his youth as a river guide. As an adult he travelled abroad before coming back and settling next to the river that he always felt was his home. He started a family. To teach his children to swim, he put them in lifejackets and tossed them in the river. He knew they would be safe. “It’s just so captivating. I can’t get away from it,” he says. He is still a tour guide, and tends different sites along the 250-kilometre-long river. “I feel responsible for it. I feel I need to help the river here,” he says.

Beaver became president of the St. Mary’s River Association four years ago. Members are deeply concerned that the great umbilical cord for Atlantic Salmon will be turned into a barren strait. The Atlantic Salmon is generally considered an endangered species, and the St. Mary’s River is a critical area for its spawning. Scientists use a spot right beneath the site of the proposed mine to count numbers of juvenile salmon to monitor the population. The association recently received a $1.2 million federal government grant to reduce the acidity of the river and help the salmon survive. Nearby, in Goldenville, Osprey Gold received a “generous provincial grant” to explore for more gold-mining potential.

Beaver, for his part, is bothered by what he perceives is a governmental disregard for nature. The environmental assessment of the proposed mine is “an approval process, it’s not a disapproval process. That bugs me. There’s nothing in place to say, ‘this might not be an appropriate place, let’s not do it.’”

Beaver and the river association started a NOPE—No Open-Pit Excavation— campaign to battle an enterprise they believe will be fatal to the river.

Other community members have been outspoken against the mine.

Paul Sobey, former CEO of the company that owns Sobeys grocery stores, donated 93 hectares of land along the St. Mary’s River to the Nova Scotia Nature Trust in 2018. Atlantic Gold wants to lay down a paved road through that protected land. Sobey has called the proposed gold mine “mind-boggling.” About two dozen seasonal homeowners in the area penned an open letter against the mine, saying the combined value of seasonal homes—$40 million—and the combined annual spending of seasonal homeowners—$3 million—will disappear if the pristine quality of nature in the area is lost.

Below Cochrane Hill lays Cumminger Lake. It is about a kilometer long, surrounded by emerald-green forest. The water is clear enough to see pale pebbles on the bottom. It is home to loons, fish and snapping turtles. Ralph Jack and Gwyneth Boutilier live on its shore. Now retired, they moved to Melrose 10 years ago. “You can’t replace this property,” says Jack.

Melrose is teeming with life. Deer are glimpsed diving into the woods. Squirrels frantically chase each other through the treetops. Young eagles float through the sky. Snapping turtles sit in the shallows of the pond with a prehistoric scowl.

At night, the sky is a deep velvet blue, with stars sprayed across like a sparkling mist. Dozens of frogs croak into the darkness. Sometimes in the woods the sound of a footstep on leaves identifies a black bear.

About six months ago, all-hours drilling began on Cochrane Hill. Giant drills bore into the land. It’s one modern way to explore for gold. Since the drilling began you might not see the stars so well, because there are strange lights in the sky coming from Cochrane Hill. It sounds like a giant construction project is underway. Boutilier and Jack are sometimes kept awake by the noise and lights.

Boutilier and Jack joined the St. Mary’s River Association about seven years ago. The group is focussed intensely on battling the mine. “NOPE is the St. Mary’s River Association right now,” says Jack.

These days, Boutlier and Jack look up at Cochrane Hill and worry what it will look like with the pit. The plan is to blast a hole 950 metres long, 450 metres wide and 170 metres deep out of the hill. It will be as long as Cumminger Lake, half as wide, and almost 20 times deeper; 27 of Halifax’s Convention Centres could fit in the proposed mine site.

“I wish they would just go away,” says Boutilier.

Tensions in the area reached a boiling point at an Atlantic Gold open house on May 23. After some initial community meetings, Atlantic Gold arranged a day with two events: a question-and-answer session and an information session about tailings management.

The first session was where the trouble started. Audience members were shouting out questions; panel members had trouble answering them thoroughly. The questions were “good and penetrating,” says Joan Baxter, a journalist who attended, but the meeting didn’t flow very well. By all accounts, that meeting was ground to a halt by a woman who walked in holding some loose papers. She interrupted and held forth about historic mine tailings. Scott Beaver invited her out of the room. After a short talk they returned. She attended the rest of the meeting respectfully. Soon after that interruption, says Beaver, Atlantic Gold’s president Maryse Belanger “interrupted and took over and said, ‘there will not be any more questions about the finances of this company.’”

In between the sessions, Beaver noticed a “strange guy that was standing in different places…not talking to anybody,” and decided to introduce himself. He says the man wouldn’t shake his hand. “He kinda grunted at me and walked away. That was it.” Nobody knew who he was.

The second session was supposed to be a presentation, with questions afterward. “Minutes before” the meeting started, Beaver says, the stranger approached him, Baxter, sustainability advocate John Perkins and a woman named Madeline Conacher. He pointed at each of the four and said, “you, you, you and you, out. You’re no longer welcome at this meeting. This is a private meeting. You’re not allowed in here now.”

Beaver thought, “Who are you? What do you mean, we’re not welcome at this meeting? It’s not a private meeting. The invitation’s in the frickin’ newspaper.” The four people told the stranger they wouldn’t leave. He said, “well, I’m calling the RCMP,” and walked away. The four waited in their seats at the back of the room.

The meeting started. After five minutes, Beaver noticed flashing blue and red lights outside the window. He moved to the front of the room and started shooting a video.

In the video, an RCMP officer is seen approaching Perkins, who seems baffled by the attention. Perkins declines to leave the room, asking, “this is a public meeting?” The plainclothed stranger is heard saying, “no, this is a private meeting.”

Perkins is soon wrestled out of the room with considerable force, despite protests from himself and other attendees. The video has been viewed over 11,000 times. “The gold mine company is using their muscle, and they’re using our own RCMP to do it.” says Beaver. “It’s not right.”

Perkins is 68 years old. Two months after the incident, “my physical injuries are pretty much healed. My emotional, cognitive injuries are still an issue,” he says by phone from his home in Tatamagouche. He says he can’t bring himself to watch the video.

Perkins is the founder of Sustainable Northern Nova Scotia, a group promoting “reasonable economic development” in the province. SuNNS has made progress blocking a proposed Warwick Mountain gold mine with community actions like signs and petitions. The mine would be dug directly on top of the French River watershed and would almost certainly foul the drinking water of Tatamagouche. Perkins was contacted by the St. Mary’s River Association for help fighting the Cochrane Hill mine.

“One of the voices that’s missing from this whole thing are the Indigenous voices,” he adds. A required step in the approval of projects is consultation with First Nations communities. In 2014 the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq Chiefs signed a memorandum of understanding with Atlantic Gold, officially recognizing the perspectives of the parties involved. This made way for the Tuoquoy mine. According to the Cochrane Hill plan, the nearest Mi’kmaw community is Paqntkek, 39 km away. Consultations have begun and, the plan says, “interactions between the Mi’kmaw and the project are anticipated to be low.”

At the end of the video, half the attendees at Atlantic Gold’s community meeting stands up to leave. “Way to make headlines!” says someone in the crowd.

Joan Baxter wakes up and shuffles into her kitchen. Wiping the sleep from her eyes, she fixes a pot of coffee. She turns on the radio and sits down with a steaming cup. She listens for the price of gold: $1,468 per ounce. Still a six-year high. She feels a familiar pang of stress.

“If the price of gold starts to drop, all of this will stop,” Baxter says by phone. She is a journalist and author who has been following the new gold rush in Nova Scotia for about two years.

More than a decade ago, she wrote about gold mining in Africa for BBC and other outlets. In Mali, she was flown to see the most profitable open-pit gold mine in the world. She looked out the window of the plane and saw something unforgettable. “We were circling around to come in to land and I just looked at this giant gash in the surface of the Earth,” she says. Huge trucks looked like “dinky toys” in the enormous pit. It looked like a disaster. It was “a pale, pale brown sandy colour, and it just went on forever and ever and ever.”

That was 2002. The mine is still operating today, alongside several others in the country. Baxter does not believe such operations bring prosperity to surrounding areas. “I’d like to point out that Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world,” she says. “If gold was going to make Nova Scotia rich, we would already be a really rich province.”

Last fall, Baxter published a four-part series jointly in the Halifax Examiner and the Cape Breton Spectator about the modern gold rush in our province. “I didn’t expect to be writing about it in Nova Scotia,” she says. She wrote about a government that added loopholes to the Mineral Resources Act and invited gold companies to explore. She estimates there are now at least half a dozen gold companies doing some sort of exploration or mining in the province. Much of the business is done in private. “The people of this province don’t have a right to see what kind of deals are being made, and what kind of protection they have, if any,” she says, “because the privacy is all on the side of the mining companies.”

She also explored the realities of the open-pit gold mine, from heavy-duty chemicals like cyanide and explosives being trucked on our roads, to the communities opposing the mines, to the mining lobby’s activities in the province. Her work has been shortlisted for an Atlantic Journalism Award.

Perhaps most concerning is the difficulty Baxter has in finding information and getting comments from the people involved. "The only way I'm ever able to get Atlantic Gold to speak to me is if I go to one of their open houses,” she says. She faces similar barriers with government. “I think I had better access to information in Mali than I do here. When I wanted to interview the minister, I called the minister up and had an interview with him. I didn’t have to go through layers and layers of media relations people,” she says. “This secrecy is new.”

Guysborough MLA and former natural resources minister Lloyd Hines told The Coast he had “no comment on the matter” of the Cochrane Hill gold mine in his riding. Atlantic Gold’s communications director declined to answer any questions and would provide no comment. The office of the department of energy and mines sent a statement that says, “Nova Scotia’s mining and environmental legislation holds companies to a high level of responsibility.” Rather than comment, Mining Association of Nova Scotia president Sean Kirby referred The Coast to a recent press release which states, “protecting the environment and ensuring ethical sourcing of essential materials like gold means doing more mining here, not less.”

Joan Baxter fears the mine will probably go ahead, because these decisions are out of the hands of the people on the ground. “Nova Scotia is my backyard,” she says. “I live here. I’m from here. I really don’t want my kids and grandkids and future generations to look back and say, ‘What were you thinking?’”

The price of gold tends to rise at times of geopolitical uncertainty. Governments can print currency; nobody can create gold. There’s only so much. Its value comes from its stability. It doesn’t rust. It lasts forever. It is flexible. It can be pounded, shaped or coiled into many different forms. Your smartphone has a tiny bit of gold inside, a wire that conducts and never corrodes. Gold can be flattened into a see-through sheet. Astronauts have a thin film of gold in their visors, filtering harsh rays from the sun. It is hypoallergenic. Dentists have been sticking gold in our mouths for over 4,000 years. A radioactive isotope of gold can be used to treat cancer.

With its warm yellow tones and eye-catching shine, gold has mesmerized us through the ages. The most common use of gold is to make jewellery. Diamonds may be forever, but gold is forever too, plus it’s money.

“Do I think it’s the best thing for the area? No. But I mean, what are we gonna do? Plant flowers and sell them for five bucks apiece? We gotta live in the real world.”

tweet this

According to the World Gold Council, all the gold ever mined amounts to 190,000 tonnes, as much as the CN Tower with three statues of liberty on top. In contrast, 1.7 billion tonnes of silver has been unearthed. Since most of the easy-to-find gold has been mined, it is now “wrung from the Earth at enormous environmental cost,” according to Jane Perlez and Kirk Johnson in The New Yorker. Nonprofit mining reform group Earthworks estimates that for every gold ring, 20 tonnes of waste (equal to 250 beer kegs, 1 loaded garbage truck or 7,000 bricks) is created by mining. The Smithsonian has called gold mining “an environmental disaster.”

Today, Canada is the fifth-largest gold producer worldwide, behind China, Australia, Russia and the United States. We produced 176.2 tonnes of gold in 2017. A 2016 investor’s handbook published by the Canadian government says, “Canada is truly one of the world’s mining nations.”

Valda Kelly is chopping broccoli for stir-fry. She and her husband Harry are at their camp (you might say cottage) near Melrose. They’ve come to escape their home in Moose River. Ever since the gold mine moved in next door, life has “reached the unbearable point.”

The Kellys moved to Moose River around 1982. Being nature lovers, they sought out a spot that wouldn’t have much traffic. They bought their house “because we love peace and quiet,” says Valda. She’s a retired nurse with shoulder-length blonde hair. Smile lines appear at the corners of her eyes when she talks. Harry is dressed to go fishing at a moment’s notice, with a camouflage hat pushed back on his tanned face. Seven years ago, the Kellys heard about a proposal for a gold mine nearby. “People kinda thought we’ll believe it when we see it, you know?” says Harry.

Five years later, he heard the diesel roar of a huge vehicle rumbling past his house. Heavy equipment and big trucks were driving to the new mine. “All of a sudden, it was happening, and the scale of it was unbelievable,” says Harry, a retired schoolteacher. Valda can’t remember hearing about any public meetings beforehand. “There was no public meeting,” she insists. The gold would be mined, and they would have to live with it. “We get it that people need jobs. Some of the people were very happy to get some employment,” says Valda.

There is a knock at the door. Not expecting visitors, Harry raises his eyebrows. He goes to the door. Valda follows, a confused look on her face. “Oh, hi!” she exclaims. In a coincidence after just talking about them, it is Kim and Liz Leslie.

The group sits down in the small living room of the Kellys’ camp. A discussion about the mine erupts. “It’s no use trying to clean” the dust stuck to everything, says Kim. “It’s the same thing, day and night.”

Liz says it’s affected her health, “my breathing especially. It gets too bad and then I end up in the hospital.” Kim has to pay a couple hundred dollars every few months to have his heat pump cleaned. “It should only be done every two years,” says Kim, “It’s ridiculous. That’s how bad the dust is.” The last time the heat pump was cleaned, “the bucket was just coal black.”

Kim’s jaw moves like he’s chewing something small as he talks. He is a slim older man with a white moustache. You can barely see his mouth move. His voice rises with frustration the more he talks.

“Who wants to live out there?” asks Harry.

“Nobody wants to,” answers Kim.

“You want to sum it up?” says Harry. “Dump trucks, dust, devastation. That’s basically what our life is now.”

“Yep,” Kim agrees.

“Mm-hmm,” murmurs Valda. The others in the room nod solemnly.

“No one ever thought it would happen,” Kim says of the mine, “not as big as it is, anyway.”

“This is huge,” says Harry.

“Oh my goodness, yes,” chimes in Liz.

“Probably about 10, 15 kilometres from our place you can see the lights, it looks like a friggin’ airport,” says Kim, “and the piles of gravel are up past the trees.”

“We drove out by that way yesterday,” says Liz. “I couldn’t believe it. My uncle had a place out there. That’s history now.”

“Your goldfish died, didn’t they, Liz?” asks Valda.

“Yeah, they did. I had them for eight years.”

Small talk continues for some time.

“Why don’t you stay for supper?” Valda asks the visitors.

The two couples eat a stir-fry supper. Then they go to a nearby beach. Kim and Liz set up a tent; they prefer not to go home. The two couples talk about their neighbours who sold property to the mine.

“They should have bought us out, too,” says Harry.

Kim shrugs. “I like my place. I don’t wanna leave.”

The shadows grow long. It is dusk. The tide washes up against the rocks. Harry and Valda leave to head back to their camp. Liz and Kim sit on the beach beside their tent, looking out over the water.

Not everyone who lives in the Melrose area is so against the Cochrane Hill mine. Some think an infusion of jobs would be a much-needed lifeline in a community parched for work. Some local businesses are dying for more customers. It’s a story familiar in many rural Nova Scotian towns. Young people have been leaving for employment, leaving behind a shrinking community.

Robie Maclennan is a mechanic who lives within five kilometres of the proposed mine site. He drives half an hour to his job at a garage in Antigonish. He couldn’t find work closer to home. He wanted his kids to grow up in Aspen (near Melrose), like he did. He believes that without jobs, the community will soon be a shell of what it once was. Since there’s no better option on the table, he supports the mine. “Do I think it’s the best thing for the area? No,” he says by phone. “But I mean, what are we gonna do? Plant flowers and sell them for five bucks apiece? We gotta live in the real world.” The Cochrane Hill mine is projected to create over 200 jobs.

Maclennan says those against the mine are jumping to the conclusion that it would cause destruction. When jobs are so important, he thinks people need to be open to anything that can help the economy. The mine might not be the best thing, but if the company follows the rules, it should be a safe operation. The Moose River waste leak is an example of things working the way they’re supposed to.

“There’s hotheads on both sides, I guess,” he says. “Nobody wants to see it ruin the river or the drinking water.”

Maclennan believes there are more pro-mine people than it seems, but most of them are too busy working and caring for their families to demonstrate their support. Others are intimidated by the passion of the NOPE campaigners. To encourage supporters to speak their minds, he posted green stickers that say “YEP.” “It doesn’t really stand for anything, it’s just the other side,” he says. Maclennan’s property has both NOPE and YEP signs, because his kids are against the mine. “I want them to know you can be on opposite sides of something and still get along,” he says.

“I get the feeling that somebody signed off on this long before it became public knowledge.”

tweet this

He conducted a Facebook poll to measure feelings about the mine. After 822 people voted, 58 percent were for the mine, 42 percent against. Not all voters were locals.

Maclennan thinks it’s unfortunate that there are now “very heated conversations between neighbours.” Lifelong relationships are disrupted by different opinions of the mine. Either way, Maclennan assumes the mine will appear soon. “I get the feeling that somebody signed off on this long before it became public knowledge,” he says.

Another person interviewed, who wishes to remain anonymous, echoes Maclennan’s concerns. He became a liaison between the community and the company to foster civil back-and-forth discussion. He got involved, he says, “because I believe in this community.” He also believes the mine is going to happen, no matter what anyone does. “We think we own our land, but we really don’t,” he says. He thinks the company will be more likely to donate to the community if there is a good relationship.

“There’s people who don’t want to see the mine happen, and there’s quite a few people that actually want to see the mine happen that are not very vocal about it,” he says, “so I have to try to stay in the middle.”

Neither expect to ever work in the mine.

Natural Resources Canada’s website says, “Canada's minerals sector is a mainstay of the national economy that supports jobs and economic activity in every region.” In 2017, there were 426,000 people employed in the Canadian mining industry.

David and Patricia Clark can see Cochrane Hill from the end of their driveway. Last year, Patricia googled “open pit gold mine” and became horrified at the idea of having one so close. “It’s the dirtiest type of mine, worldwide,” she says. “It’s more toxic than coal mining.” Accidents involving mine waste seem common, and disastrous, around the world. Giving the benefit of the doubt, she thought maybe Canada would have high-enough standards that it could be done safely. Then she found the Mount Polley disaster. Worried the same thing could happen in Melrose, Patricia now believes the proposed mine is simply not safe. It can’t be done without consequences. “There is no such thing as clean open-pit mining,” she says.

The Clarks don’t know what will happen to their property. If the mine opens, and the project expands, their land could be expropriated. It happened in Moose River. As long as the price of gold is high, this business will grow and change. “It’s like David and Goliath, only we don’t have any illusions we’re gonna win,” says Patricia. Atlantic Gold was sold for $722 million in July to a bigger Australian company, St. Barbara Limited.

David and Patricia sit in their living room as the sun sets, thinking about the future. They have lived here for 23 years. They say they will move if the mine goes ahead. “I never carried anger before,” says David. “Now I do.”

Outside, under the star-splashed sky, frogs croak a chorus near the murmuring stream. A black bear wanders through the trees, completely silent except for crushing leaves underfoot. In the distance, the whine of a high-powered drill echoes through the woods.

Andrew Bethune is a writer from Halifax.