Evan Walker and his wife, Krista, thought they had found the perfect home to raise their five-year-old son, Tristan: Three bedrooms, good neighbours, on a quiet cul-de-sac in Bedford’s Southgate neighbourhood. All for $2,200 a month. They can walk their son to his pre-primary classes at Bedford South Elementary. Other kids live on the street. Parks and trails abound, from the forested Old Coach Road Trail to the nearby Paper Mill Lake. In the 18 months the Walkers have lived there, Evan has taken to gardening. He’s even re-seeded the lawn.

“It’s a pretty nice place to raise a family,” he says, speaking by phone with The Coast.

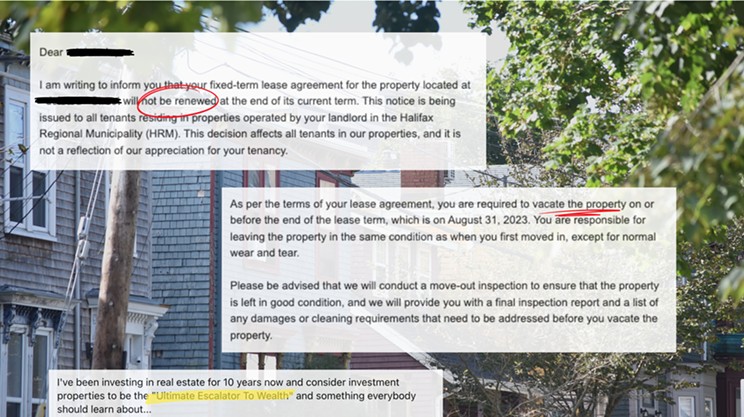

That changes soon. On Saturday, July 1, the Walkers will be forced to leave the townhouse they’ve called home for the last year and a half. Their fixed-term lease is ending. The landlord, Evan says, is raising the rent to $3,195 per month—a “total blindside,” he tells The Coast, and a bridge too expensive for what they can afford. (We’ve changed Evan’s name, along with his family members’ names, to protect their privacy as they search for new housing.)

“[These] guys tell us how wonderful we are for 18 months,” he says. “We’ve never missed a rent payment… now I don’t think we’re going to find [a place] anywhere.”

The Walkers have been searching for housing for the better part of three months, but find themselves in a bind: They can’t afford a down payment on a house or condo, and the rental options are scarce—and mostly geared towards singles and couples.

“I’m usually a pretty hopeful guy, but at some point, there has to be some sort of intervention,” Evan tells The Coast.

The Walkers aren’t the only Haligonians feeling the pinch. Amid a tight Halifax rental market, some are calling on the province to protect tenants caught in fixed-term leases—and to clamp down on landlords taking advantage of the legislation’s loopholes to skirt around Nova Scotia’s 2% rent cap.

Rental housing rates inch higher in June, report finds

According to the latest Rentals.ca report, which compares asking prices of vacant units across Canada, the average rent for one-, two- and three-bedroom Halifax apartments are up 9%, 2.3% and a staggering 38%, respectively, compared to the same period last year.

If you were looking at a vacant three-bedroom apartment in June, per the latest report, chances are that it would set you back $2,768 per month. Evan says most of the two-bedroom apartments he and his wife have looked at range from $2,300 to $2,700—a far cry from the 2,800-square-foot home they were able to rent for $1,800/month two years ago, before they moved into their Southgate townhouse.

If you were to follow the Canada Mortgage & Housing Corporation’s guidelines, which posit that for housing to be considered “affordable,” it must not exceed 30% of your monthly income, then a family would need to pull in just over $9,200 per month—or $110,000 per year—to afford a newly-vacant three-bedroom Halifax apartment. Most Nova Scotian households were grossing somewhere closer to $71,500 a year in 2020, per the province’s Finance and Treasury Board. And single-person households are earning closer to $36,400.

The math doesn’t add up.

“Nova Scotians are still getting paid like Nova Scotians,” Evan tells The Coast. “And none of them can afford to live here.”

“Nova Scotians are still getting paid like Nova Scotians. And none of them can afford to live here.”

tweet this

He and his wife are actually faring well, by the province’s standards. Evan works in construction management. Krista works in human resources. The two combine to earn around $150,000 a year—but because of his credit score, which he describes as “not horrible, but not good,” he worries property management companies won’t give them a chance. The family has been turned down for three vacant units already, he says—despite glowing references, co-signers and money to cover three months’ rent up front.

“You see stuff in the news all the time of people that are getting stuck in a situation who have a lot less means than my wife and I do. And it’s freaking me out,” he says.

The Walkers would like to keep their son in the same school catchment area for the fall, if possible. He’s made friends. But they know that might be an uphill battle.

“We want to give him some sort of stability—he’s five, you know? And then of course, what happens if we get a place and then we have to move in the middle of next year?”

Fixed-term loophole needs closing, advocates say

Nova Scotia’s governments have tried to wrest control of a housing affordability crisis “never seen before in our province” by introducing a rent cap in November 2020, and extending it on an interim basis every year since then. Premier Tim Houston made it one of his earliest actions upon his 2021 election to extend Stephen MacNeil’s rent cap until the end of 2023. The province called it an effort to “protect tenants” while it focused on housing supply.

“The housing crisis is real and Nova Scotians expect us to act,” Houston said in October 2021. “We’ll do what needs to be done to make sure Nova Scotians can afford a place to call home. We will not wait.”

By law, landlords in Nova Scotia with ongoing tenants are barred from raising rents by more than 2% in any 12-month span. (That changes to 5% on January 1, 2024.) There’s one major caveat: The rent cap doesn’t apply to vacated units. And landlords are taking notice.

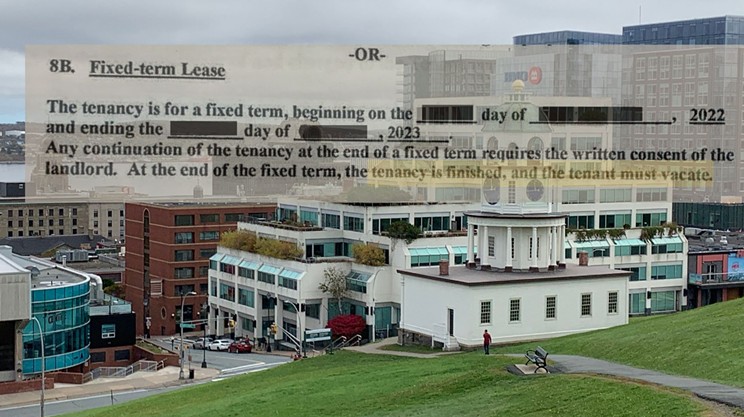

One common thread links the Walkers with other renters who’ve found themselves about to lose their rental housing: Nearly all of the tenants The Coast has spoken to in recent months have been on fixed-term leases—defined in Nova Scotia’s Residential Tenancies Act as a rental agreement with a predetermined end date, as opposed to periodic leases which roll over on a monthly or annual basis.

“Due to changes in the Tenancy Act, the industry has moved away from month-to-month leases and moved to fixed term so that both tenants and owners are on equal footing in regards to the terms and options of the lease,” one property manager told The Coast by email last fall.

Fixed-term leases have been written into the Tenancies Act for decades and exist in various forms across Canada. And there are indeed benefits to both tenants and landlords, if both parties agree on when they want the lease to end. But the balance of power is far from equal, tenancy advocates argue—and the widespread use of fixed-term leases is pushing tenants into precarious positions.

Katie Brousseau has a frontline view of how tenancies have changed in Halifax. A community legal worker at Dalhousie Legal Aid, she says she hears “almost exclusively” from clients with tenancy worries—and increasingly, those worries involve fixed-term leases.

As tenancy options go, fixed-term leases offer “far [fewer] protections” for tenants than month-to-month or year-to-year leases, she told The Coast in October. Unlike periodic leases, which roll over when they reach their term end (say, at the end of a month or year), fixed-term leases don’t—which means tenants are left without any security of tenure. If a landlord wants a tenant to leave at the end of a fixed-term lease, “they’re not obligated to have a reason,” Brousseau says. “So it makes it very difficult for folks on a fixed-term lease to know whether or not they'll have a continued tenancy.”

One of the greater dangers is that tenants can be unaware of their own housing precarity. Evan says he didn’t think twice about signing a fixed-term lease until it was too late.

“We never even thought of it,” he tells The Coast. “We didn’t really see the stories of these things [when we signed the lease]... we ended up getting burned by a damn loophole.”

Could Nova Scotia follow PEI’s example?

Some affordable housing advocates have called for Nova Scotia to tie its rent cap to units, rather than tenancies—which would take away the incentive for landlords to get rid of tenants in order to circumvent the 2% (and soon to be 5%) cap. Prince Edward Island has followed that model for years—though there, too, there are limitations: Rents aren’t registered with the province, meaning without a record of a prior tenant’s lease, landlords could, in theory, raise the rent for new tenants without limits.

Thus far, any changes to the cap structure have been met with indifference in Nova Scotia’s legislature. In an emailed statement provided to The Coast, a provincial spokesperson replied that Nova Scotia’s government is “not considering” the idea at the moment.

“We are always working to balance the rights and needs of tenants and landlords,” the spokesperson said, adding that the government is “reviewing” how landlords are using fixed-term leases.