In the beginning

Two weeks. Remember when the pandemic was supposed to last two weeks? Now, it’s been almost two years since we “buckled down,” stocked up on toilet paper and cloth masks, and first locked down due to COVID-19.

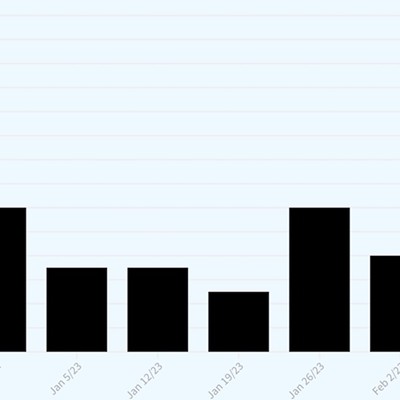

Now, 22 months after the virus first reared its ugly head in Nova Scotia, we’re instead planning for a “new normal,” wouldn’t be caught dead in a cloth mask unless there’s an N95 underneath, and we’re in the fourth wave of COVID and its many variants.

Like most Nova Scotians, I’ve followed the rules to the best of my ability all along. I’ve tuned into numerous press conferences and had the privilege of asking questions to Doctor Strang and three different premiers.

But two years in, and like most Nova Scotians, I’m exhausted.

“I think we were getting tired of it in April of 2020,” says Roy Ellis, a Halifax-based therapist specializing in grief counselling. He is the bereavement coordinator for the integrated palliative care unit of Nova Scotia Health.

“I became sort of an expert in traumatic loss,” he says of his day-to-day life speaking to those who’ve lost someone. “And the ways in which grief sort of intermingles with our life, and living.”

Before his current position, which he’s been in for 12 years, Ellis was a hospital chaplain, and he also has experience helping people who work in what he calls “high loss” environments like shelters and Alzheimer's units.

Ellis says COVID has affected us all in ways similar to the people he helps. We’re mourning the loss of two years of “normal” life, as well as the personal, career and education opportunities lost within those two years.

“Grief is any loss of something meaningful, important, beautiful, loved or significant. Something that has entered our world that we want around, that we become attached to or at the very least becomes meaningful,” Ellis says. “And whether that’s just a coffee shop down the street, or involvement in intramural sports, or the ability for your kids to go to school, or your loved one who died alone in a hospital because of the restrictions during COVID—all of those small and large losses constitute grief.”

Slow-motion disaster

For some, that also involves the loss of a close loved one due to the disease or otherwise, where grieving—which is usually a period that family and community can wrap around you—was severely impeded by public health restrictions.

While for others, COVID has been a large-scale, cultural shift. Ellis calls it a “slow-motion disaster” we’ve watched from afar.

“Those are going to be very different experiences, but each of them is a loss,” says Ellis. “A loss doesn’t necessarily have one specific, formulaic way of feeling or thinking.”

And the enormous weight of the pandemic hasn’t been the only thing pressing down on us in Nova Scotia. The last time The Coast spoke with Ellis was in April 2020, just days after the Portapique shooting.

At the time, it was a period of mourning for the entire province. “This happened almost two years ago, this has been hovering with us, this huge cultural, province-wide grief that I’m not sure we ever fully embraced or moved into,” says Ellis.

In the months directly following that, even more tragedies struck Nova Scotia: the Northwood COVID outbreak, the tragic disappearance of Dylan Ehler, the death of Snowbird Jen Casey, and the helicopter crash in the Mediterranean. Then the William Saulis fishing vessel sunk, the housing market hit a crisis point and the Mi’kmaq lobster dispute finished off 2020.

Not to mention the multitude of ongoing global crises. “This global shift to the right is happening, this move towards anti-democratic politics,” Ellis says. “These environmental shifts that have gone into overdrive with heatwaves and flooding, wildfires. A health care collapse that we’re constantly being told we’re on the verge of, our education system is in crisis ‘cause of COVID. Those are huge things.”

Dealing with ambiguous loss

So how do we come to terms with all these tragedies, as well as the ongoing pandemic and the losses that come with it? There’s no simple answer.

“I think it’s very difficult to acknowledge an ambiguous disaster,” says Ellis. “This whole experience of COVID, it’s an ambiguous loss.”

That ambiguity comes from the fact COVID is causing complex losses and is still ongoing, and means most people haven’t even recognized it as a loss.

“We know something bad is happening, we know our lives have changed. We know on some level that we don't want to admit that things aren’t going back to pre-March 2020, whatever world we have is going to be a new world,” Ellis explains. “But we can't always put our finger on what the losses are.”

For me, sometimes the world seems almost normal. Sometimes, in a small group of friends, I forget why it’s a small group. Sometimes while walking outside on a cold day, I forget the face mask is protecting me from a potentially deadly virus, and imagine it as a soft scarf keeping my face warm.

“Sometimes we get the things that we want, sometimes life almost appears normal, and then it fluxes out and it's really abnormal,” says Ellis. “So start to grieve and then wait, are we supposed to grieve now that we got it back? There's a lack of clarity in whether we can actually plant our flag in the mountain of grief because it seems to evaporate on us all of a sudden.”

So the first step is acknowledging that grief. The fact that grieving COVID losses might be different than other losses. “I think we're called to really approach ourselves and our grief and our losses in very different ways than you would with a straight-up, ‘my grandfather died,’” says Ellis.

But it’s hard to do that while COVID is still ongoing, a now-chronic condition of our world. “We're chronically disconnected from the people, and the events, and the places and the experiences that make us feel secure, safe, seen and soothed,” he says.

Those four S-words ring in my head as Ellis continues, “if we're always in the process of grieving, there's never really any sense of closure. We don't have a chance to heal one thing before the next loss appears, so it becomes this great stew of losses that we find ourselves marinating in.”

Living with grief

It doesn’t sound easy. But if we’re finally ready to begin grieving the pandemic almost two years in, how do we do it, then?

“I think all of this ambiguous loss creates a really fierce and important call into the present. We're not a society, a culture, that has really emphasized being present as human beings to our body, to our minds, to our souls and to our spirits. We're very much into entertainment, we're very much into success, status, activity.”

So, Ellis says, for people who have put value into their jobs, their education, their social life or going to the gym, their immediate disappearance has left a hole. “The nature of these losses cut off our access to those distractions and our typical avenues for self-esteem,” he says.

Now we’re being forced to find value in new things. A lot of people have done this throughout the pandemic, whether they’ve quit their jobs or moved across the country. But can you do it without taking such drastic steps?

“Some people I think have heard too much of this, we talked a lot about this, and I think people go, please give me something else something other than that,” Ellis says. “But, you know, walking in nature has proved to be super, super helpful for people.” On top of the benefit of exercise releasing oxytocin and dopamine in our brains, Ellis says “the size and the scope of nature can hold all of our pain.”

“It's always larger than us, and there's a sense of being nested in nature,” he says. Getting into nature lets humans slow down and regulate their breathing and emotions.

“We can't be present to ourselves if we don't slow down and bring the blurring, speeding, dizziness, of our distress and our loss into focus by slowing down,” he adds. “And that might mean walking slow, but it also means thinking slow, and shutting things off, like our phones and our computers, and sitting in a chair by a fire, looking at a window and actually taking a moment to see what happens inside if we don't propel forward in our distress and anxiety.”

What happens might vary, but it’s probably going to be a realization of what our basic needs are. Observe yourself, see what you’re anxious or stressed about, Ellis says.

“Asking ourselves not just what we want, but rather what we need as humans is a question that few of us take the time to ask,” Ellis says. “And it's almost always I need somebody to see me, somebody to hear me, someone to touch me, to care for me.”

Then it’s a matter of gathering those people around you—physically or, if restrictions require, virtually. For some, it’s making a change to your “close contacts” list, while for others it’s growing closer to the people you already spend time with. Ellis disagrees with the idea that “if we're stuck with five people, that we're just going to annoy each other more and more and more.” For him, it’s the opposite: building relationships and learning more about each other.

While rapid test kits and close contacts are limited, what isn’t in short supply are nature and love. Ellis says it comes down to being grateful for what you can still experience, like snuggling with a pet, child or loved one, and taking a walk through the woods on a brisk day and inhaling deeply. And don’t just imagine it, live it.

“Take concrete action to not just make all of this in our heads, but ask: What can I concretely do? What action can I take? Writing a letter, extending a call, baking a pie for my next-door neighbour. We still have our world, and even though our world has shrunk during COVID, we have way more ability to impact the world than we know.”