On Thursday evening, Mar. 21, three University of King’s College students stayed outside the largest lecture hall on campus discussing what they’d just heard. It was dark and tempestuous outside. At that hour, very few people were moving around the school.

In a corner by a window and an exit door, they stood together in a circle. “I'm very happy I went,” says one. “It was a lot of stuff that I already knew, but it's a good thing to see on campus.”

“People want to talk about it,” says a second. “People don't know how to talk about it. Everyone's scared. Everyone's scared of alienating and being alienated. There's just so much fear.”

All three students have chosen to remain anonymous. All three say they’re informed on the historical context of the conflict in the Middle East, but came to Thursday’s lecture looking for advice on having pro-Palestinian conversations within the Jewish community as well as looking for ways to turn their solidarity into action.

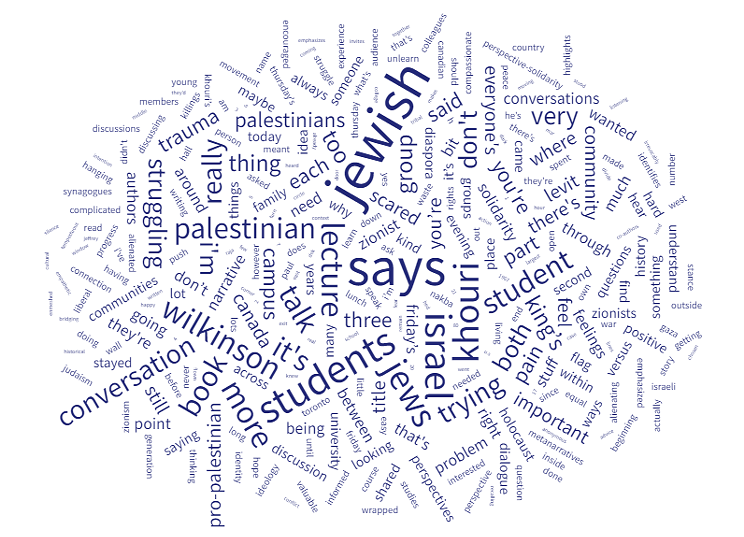

The lecture they’re coming from is a discussion of the book, The Wall Between: What Jews and Palestinians Don’t Want to Know About Each Other, with the authors Jeffrey Wilkinson and Raja Khouri who have flown in from Toronto. Says its authors, the book was written for the Jewish and Palestinian diaspora living in Canada and the U.S., with the intention of bridging the divide between both groups through empathetic listening and compassionate conversation. What’s more, their book emphasizes why this is important for progress to be made, writing “Today, Jews and Palestinians are irrevocably enmeshed in the two metanarratives of the Holocaust and the Nakba. As long as the recalling of one is used to silence the other, no real progress can be made.”

Their book makes the case for how dialogue and connection across cultural tribal lines is needed today more than ever. Khouri is a Palestinian-Lebanese Canadian and the co-founder of the Canadian Arab-Jewish Leadership Dialogue Group. Wilkinson is a Jewish American living in Canada who works as an educator and facilitator within the Jewish community on issues relating to trauma, memory and the Israeli-Palestinian struggle.

In a November op-ed for The Walrus, the two write that trauma “acts like a force field that repels narratives that appear threatening to our own perspectives. The respective traumas…have kept us each in our camps, resistant to viewing the other and the other’s pain.”

The three King’s students are choosing their words carefully, as they reflect on Khouri and Wilkinson’s hour-long lecture, whose thrust came through questions and conversations at the end.

“I was curious to hear them talk and I wanted to know, what does King’s think we want right now,” says one–a Jewish student trying to find ways to speak within their Jewish community about Palestinian rights and freedoms.

Says the student, “I came because their messaging is important to me. I am really interested in the ‘perspective-solidarity movement,’ which is where I find I'm comfortable trying to push myself to not only be interested in solidarity, but also really pro-Palestinian solidarity, because I'm still really trying to unlearn the Zionist stuff that I grew up on.”

Wilkinson and Khouri’s book had been published a week before Hamas’ deadly attack on Israel on Oct. 7.

Since then, they have been travelling to university campuses across North America to encourage students to talk through complicated feelings about identity, ideology, pain, sympathy and horror. Today, it can seem like there’s only one right thing to say. But, people are struggling over feelings of powerlessness and polarization, and don’t know how to talk about that. The narrative around Israel-Palestine has become, “You’re either in or you’re out,” for acknowledging the unequal killings and forced starvation of Palestinians in Gaza by the state of Israel. But, overcorrecting that polarizing narrative can go too far, says one King’s student.

“I think this ‘two-sides’ thing has been really debunked on the internet, or that there’s two equal perspectives that deserve equal time,” says a student in reference to how Wilkinson and Khouri lend credence to both Jewish and Palestinian metanarratives of intergenerational trauma that build the wall between them. “People obviously are really scared of doing the wrong thing. If you're not super informed, or don't have connections to people that are in it, you’re thinking ‘What's the right thing to do?’ And like [both authors] said, there's this ‘pick-a-side’ thing, which is just so dumb, but I think there really is that pressure and this was definitely a ‘don't-pick-a-side’ thing…maybe a little bit too much, though.”

"The feeling of loss, the feeling of things done, seemingly in my tribes name that I can't abide by. Yet I still have great compassion for my community and the trauma they experience. So I live in a lot of strife internally. I get support from that from my buddy Raja.

"But I really want to be clear with you that we have some big dreams about what we can do together. But that doesn't mean we aren't deeply aware of the asymmetry in power between the groups. And we talked about it every day. And we are led to believe that you got to pick: you can either be empathetic to the Jewish experience or the Palestinian one. And we say, "no."

We say that you can be justice-centred and fight for Palestinian rights and still care about the trauma that makes it hard for Jews to accept the Palestinian story. And that's a difficult thing for many people. And we don't expect everyone to take that path, but that's our path."

Despite critiques of the lecture's framing from the audience, one student who identifies as Jewish and pro-Palestinian says “I don’t think it was a waste of time–I think it’s a starting point.

“I'm really critical of these things because I've spent many years trying to unlearn the Zionism that I was taught as a kid. But I don't think it was a waste of time. It's a perspective that people need to hear even though I think it was a bit too focused on the Jewish victim experience.

“That's what bothered me was their [focus on] 'Jews are victims too.' I just think they didn't speak enough about Palestinian pain and trauma and I think they spoke about the Nakba as only a displacement, which I think is a bit inaccurate–I don't think they emphasized the Palestinian pain in the way that they emphasized the Jewish pain.

“But I still think it's valuable, and if someone bought me the book, I would read it.”

Says Khouri during the lecture, "Our book is in four parts: The first part talks about identity, trauma and victimhood, and memory and how these things work; The second part, we take some three major subject areas that are relevant to us. Some topic, one is anti semitism. The other one is Zionism and the Nakba. And the third one is Palestinian resistance. And then we look at how each one of these subjects, these are big subjects right, are perceived by each community. And why did they get there? How is it impacted by trauma, by groupthink, by propaganda. [For example], how does anti-Semitism, the idea, come across to both of these communities?" And finally, what is the way forward?

Following the lecture, a second student who identifies as Jewish and struggling to hold pro-Palestinian conversations with their more conservative family members says, “I wish they had spent more time on the nitty gritty stuff and less on the crash course history of the region.”

As the lecture rolled into questions, Daphna Levit’s hand rose. Levit sat close to the front with a long braid of white hair tracing down her back. Levit is a Religious Studies instructor at Saint Mary’s University and has substituted at King’s for Daniel Brandes’ course on Hannah Arendt. She is the author of two books on Israel/Palestine, one of which shares a publisher with The Wall Between, entitled Wrestling With Zionism.

“The title of your book is Jews and Palestinians,” says Levit. “And I think Jews are not the problem.

“I think that you are suggesting in the title of your book that all Jews are Zionists, and that the Jewish story is exclusively [beginning] since the Nakba–you even said at some point that the Jewish story is the Holocaust which happened 80 or some years ago.

“There's an incredible wealth of Judaism and depth of Jewish studies that precedes Israel. So I find it a little bit difficult as an ex-Israeli who served in the 1967 war as a lieutenant. I feel the trauma of that war enormously and have been a peace activist all my life.

“The title upset me because the dichotomy is incorrect. The problem is Israel, and your title suggests that it's Jews.” Levit acknowledges that they were writing for the diaspora and in the West but still wonders whether they consider their title to be reinforcing the stereotype that all Jews are Zionists. “I wonder why you didn't use Israeli versus Palestinian?”

Wilkinson is first to respond. “It's certainly something we've been asked before, and I'm not going to try to defend it.

“Our point was that the mainstream of our Jewish communities that are still in Canada, even in reform, liberal synagogues, is a pro-Israel stance. Lots and lots of Jews are not, but that is the general stance.

“What we were trying to get at was, can these communities actually do exactly what you said, see each other not as a political ideology, but as people who have had a shared history of pain and suffering, and can learn from each other. So, in that sense we’re actually trying to erode this idea of the Zionist versus other forms of Judaism.

“I want to be clear, I get your point. And you're not the first person to ask it.”

Khouri answers Levit next, saying her question has been asked from both sides.

“There are many Palestinians or Arabs who say, ‘We don’t have a problem with Jews, we have a problem with Israel.’ So, yes, we are talking about the dominant ways that people think and act in each [the Jewish and Palestinian] communities.

“I can tell you that after 17 years of dialogue with Zionists, I am now maybe getting to understand the Jewish connection with Israel.” Stress on the maybe, meaning he’s beginning to empathize with the positive feelings between the Jewish diaspora and the idea of Israel–a place that some have never seen.

Khouri recalls how this hasn’t been an easy road to understanding. He describes going to synagogues for talks with his Jewish colleagues and seeing the Israeli flag hanging inside and thinking, “What is that flag doing hanging inside a place of worship in Canada?”

“To me, Israel is a repressor of my people. It’s a country with strong armies that is oppressing my people. Why is there a flag of that country in a synagogue in Toronto? I couldn’t wrap my head around it.” Khouri says he’s come to hear, and feel from those he's spoken with, that, “to the overwhelming number of Jews in Canada, Israel is very important. Israel is a safety blanket. Israel can protect Jews should there be another attempt at a Holocaust.” For that, he practices compassion when he speaks with Jewish colleagues and students about their complicated relationship with Israel–the place and the idea.

Back to the three students in the lobby late Thursday evening.

Says the first student of the situation at King’s, “I think there's maybe one or two Palestinian students here and way more Jewish students–but I don't want to further push this Jews versus Palestinians thing because I was also irritated by that in the lecture, the 'you're in or you're out' [narrative]."

There is a King’s-Palestine group on campus. The students say having that group is amazing and important, and that the group does allow a space for multiple perspectives, if imperfectly.

“But I think in these groups there should always be room to ask questions, and I do think this [talk] encouraged that–but I think people needed more time for both. People can look up the history if they want to, and like that's really easy, but to have a conversation with someone that you think knows something is way more valuable than being lectured by them. It's this conversation piece that's missing.”

The following day, Wilkinson and Khouri hosted a lunch and conversation for just students for over two hours down the hall and up the stairs. Says one student who stayed late after the lecture, "I can't make it tomorrow, which is sad,” but if they could they would want to say, “Overall, I'm just confused about what to do.

“I want to be able to talk more about it and I feel very isolated from other Jewish people and with my fellow students, because you never really know where anybody stands and you don't know how anybody's gonna react to what you're going to say. I think I would like for a lot more humanizing to happen on campus.”

As for Friday’s conversation, one student who was at both their lecture and lunch, Paul H., says around 20 students showed up Friday and stayed well until the end. Paul H. says the conversation was positive and interesting, and that “both authors were great at facilitating discussions.”

Says Wilkinson on Friday’s conversation, “it was an extremely positive, open environment where students shared their honest feelings, reactions to each other and listened deeply and intently to anything that we had to say.” He says there was a “very big mixture of viewpoints, experiences and backgrounds” across the students there.

Says Khouri of Friday’s group, “at least two thirds were Jewish.”

“Not all Zionist,” says Wilkinson.

“No,” says Khouri. “Most of them are struggling. One of them as she was leaving, she told me, ‘When you said to us that our struggling gives you hope, that meant a lot to me.

It meant that I'm on the right track.’

Khouri had wrapped Thursday’s lecture saying that younger generations of Jewish people in the West are the biggest defenders of Palestinian rights, citing groups like Jewish Voices for Peace and Independent Jewish Voices. Khouri says “they are the young folks without that influence of trauma, looking at what’s happening in Palestine and saying, ‘Not in our name. Not in our name.’ And that’s where the hope is.”

Says Khouri on Friday, “This is new, that you have a generation of Jews that is struggling and trying to understand Zionism and what it means to them–trying to make a judgement about it, if it's something they want to have as part of their identity or not. [That struggle] among a large number of them—that's very new.”

Neither author shared specifics about what students said because privacy is an important part of this work and is an integral part of touring their book.

Of Friday’s conversation, Wilkinson can say, “we were impressed, encouraged by the level of discourse that they entered into,” and that discussions of how to talk to family or other Jewish community members who disagree with them was “very much in the air.”

However, Wilkinson says, “ I don't want you to be misled: there are still a good portion of young people who feel very attached to Israel, but they're struggling. They recognize the immorality, the death, and they are uncomfortable with it. So, they're struggling in a different way. The older generation just kind of puts aside all the other harms and just kind of focuses on, 'I need Israel,' whereas these guys need Israel, but they're going, 'Is this okay that I need Israel? They're struggling.”

Khouri says he loved being on campus, which is “always a special experience,” and says the “hunger of students for this kind of discussion was obvious–They wanted to learn, they wanted to know more, and they wanted to talk to people who can help them.”

And finally, a return to the three students on Thursday evening, discussing Wilkinson and Khouri’s choice to not use the term “genocide,” to describe the current round of killings in Gaza by Israel.

Says the first student, these choices are hard. “How do you bring people in but also get things done? I think that's the question: when do you compromise and when do not?”

Says the second, “Isn’t bringing people in a part of getting things done, though?”

“Yes, and conversation. But at the same time it's hard to have these constant conversations with people that are so stuck in their narrative. It's exhausting. What I've been experiencing is trying to not let the Jewish community that I'm a part of fall apart because everyone's fighting. It’s part of the [compassionate] work, like what they said, but I also think sometimes it's hard to always be trying to unravel what someone else's entire existence is wrapped up in.”

“I feel like as a Jewish person with a more liberal view than the rest of my family, you're also working through your own stuff. And you want to do both, but there's only so much you can do and give.”

“Until one side [tells you], ‘You're too pro-Palestinian for this group and you're too Zionist for this group,’ and that’s where these ‘perspective-solidarity’ people live, in the ‘too-much-not-enough’ debate.

"But then you’re an apologist. Then you’re a traitor.”