August 18, 2021, was a defining moment for Halifax. That was the day city hall decided to evict houseless people from public lands, sending municipal workers and police out at dawn to tear down shelters and tents. And it was that Wednesday afternoon hundreds of citizens amassed at the former Halifax Memorial Library, hoping to protect the Haligonians sheltering there from their city. The ensuing shelter siege, with its pepper spray and violent arrests, left city council contrite and eager to do better by its most vulnerable.

At the first meeting of Halifax Regional Council after the siege, councillors voted to let chief administrative officer Jaques Dubé spend $500,000 on something, anything related to emergency housing. Soon enough, a solution was found. The powers that be in Halifax have maintained the narrative that people don’t have a right to set up crisis shelters on public property. But it would be okay for the city to provide temporary housing, complete with plumbing and electricity, in the form of “modular units.”

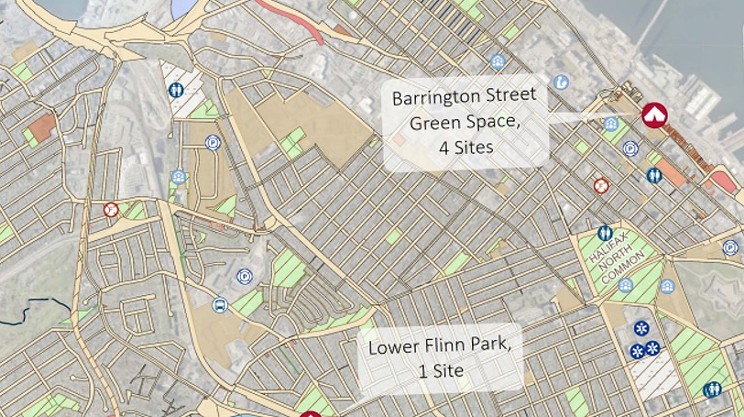

Early last fall, not two months after the shelter siege, the city was promising to have people living in modular units “before the snow flies.” However, a long list of roadblocks including mould and supply chain issues managed to delay those units. It was just last week, nearly 10 months after the siege, that people started moving into the last set of modulars, located at the Centennial Pool parking lot in Halifax’s north end.

Oh, and the bill for the modular units is almost $3.2 million, nowhere near the $500,000 budgeted for housing help.

To find out more about council’s thinking, The Coast made a request for correspondence—enabled by Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy legislation—that included any emails between city staff and council with the phrases “modular units” or “temporary housing.” We made the FOIPOP request in November 2021, for council communications from January 1, 2021 through our November filing. In April 2022, we received an electronic package of 755 pages of documents, and got to work reading them. Now that all the modular housing units have been installed and the city has issued its “final update on these emergency accommodations,” the full story of their genesis can be told.

“Our. Web. Site. Strategy. Sucks.”

Let’s start at the beginning. It was late December 2020 when an anonymous group of people created Halifax Mutual Aid and began building crisis shelters for Halifax’s growing unhoused community, which at the time was fewer than 400 people. (Now, it’s more than 600.)

Halifax Regional Council caught wind of the unauthorized project and decided to put a stop to it. The HMA had no building permits, and while its Tyvek-clad plywood shelters could be erected cheaply and quickly, they lacked running water, electricity and fire safety systems, giving the city lots of room to say they violated various standards.

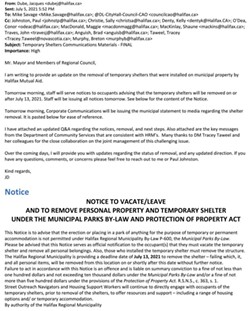

On January 24, HMA got word that the city was planning to remove one of two crisis shelters recently erected just off the Dartmouth Common on Geary Street. When public backlash ensued, HRM eventually backed off. Around 9pm that night, councillor Sam Austin took to social media to defend the city’s actions. “HRM isn't forcibly evicting anyone,” Austin tweeted, echoing language the city used on its own website.

Further driving home the city’s position, a little before midnight on the 24th, Sally Christie, a senior advisor to CAO Jaques Dubé, emailed the mayor and councillors a list of nine talking points. (This sort of email from city staff to the politicians would become common as the housing crisis developed.) “The points below can be used in response to residents and media,” Christie wrote. “As yet, there have been no media inquiries.”

The notes included the promise that the city “will not force the eviction of residents from homeless encampments unless and until their need for adequate housing is met.” Also, the Halifax Regional Municipality “has adopted an empathy-based human rights approach to homeless encampments that recognizes the human dignity of people experiencing homelessness.”

Early the next morning, councillor Pam Lovelace was on message to the public. “HRM takes an empathy-based human rights approach to homelessness,” Lovelace said in a January 25 tweet, “HRM recognizes the human dignity of people experiencing homelessness.” On January 26, councillor Waye Mason tweeted that “we don’t want to create permanent installations of substandard shelter. Ideally, the province rents a hotel and all the folks get housed.”

But behind the scenes, out of public view, councillors attempted to provide solutions to what became the city’s biggest problem during the homelessness crisis: its messaging.

“Our. Web. Site. Strategy. Sucks.” said councillor Paul Russell in an email to other councillors and the CAO on January 25. “I did a search for homeless, and encampments,” he explained, “but couldn't find anything there.” What he did find—the screenshot Russell sent to his colleagues—was the city’s COVID-19 landing page. “We need to do better with communications. I know we're working on it. This is an example of something that needs to be fixed.”

Responding to Russell, councillor Tim Outhit said he and his colleagues “need training on how to use social media and how to address a sudden crisis (alleged or real) when they arise.”

“Show me the units”

On February 11, CAO Dubé sent an email to representatives of the province, saying the city was prepared to cost-share hotels if they could “simultaneously remove the sheds,” which he also called “unsafe shanties.” Despite K’jipuktuk being unceded Mi’kmaq territory, which practically every HRM staffer and councillor acknowledges in their email signatures, Dubé called parks “our lands” in a March 5 email.

In that same email, which is labelled “Private and confidential—not for forwarding or dissemination in any form,” Dubé tells council about a potential housing option that fell through. “Last week, Housing NS advised they had a short-term solution through the immediate acquisition by a not-for-profit group of a 18-room boarding house property on Pepperell Street in Halifax. It turns out however that the property is encumbered by leases until this Fall thus not a short-term solution at all.”

With that house unavailable to offer as shelter to people sleeping outside, Dubé outlined his plan, “that I approved this morning,” to provide “hotels or other short-term accommodations, with supportive services provided by community partners.” As part of the plan, “The Municipality will communicate that any shelters still in place on municipal land on April 30, 2021 will be removed and/or moved.” Dubé signed off the email “Kind regards, amities, wela'lioq.”

By late April, the official HRM count was nine HMA crisis shelters on public property. Dubé told HRM council that two-week eviction notices would be issued “immediately following the current lockdown due to COVID restrictions.” In that same email he cautioned: “Once the plan is operationalized, the specific day of removal for each shelter will not be communicated in advance.”

A few weeks later, Dubé wrote an email to the province. “In confidence, we will serve notice in late June on the residents in the shelters and tents in HRM parks and lands that they need to vacate within two weeks.”

The original plan was to issue notices on June 23. But HRM delayed that after a rally in support of the shelters on June 21. As public interest in the housing crisis grew, the city was forced to construct a new strategy.

By early summer, HRM had settled on its messaging. The city’s position was that “housing as a human right does not mean that this right can encroach upon the rights of others,” a phrase that appears 15 times in the package of documents The Coast received.

HRM planned to remove all 11 HMA shelters by July 13, as Dubé informed council on July 5. That email from Dubé included a copy of a statement the city would release publicy the next day.

The statement opened with the stick of eviction: “A deadline date of July 13, 2021 has been given to remove the shelters—failing which, the shelters, and any personal items contained within the shelters, will be removed by the municipality on or shortly after this date without further notice.” But it also contained a carrot.

“From the outset, the approach has been to allow occupants of homeless encampments to remain until adequate housing has been identified and offered,” the statement said. “The province has been working to ensure all current occupants of the temporary shelters will be offered a temporary accommodation option that can bridge to permanent housing.” There weren’t any details on what those temporary accommodations would be.

In public, councillors were in support of the plan. But behind closed doors, they had questions.

“Will we be making someone available to speak to the media?” asked Austin in a reply to the July 5 email. “If not, it will automatically fall entirely on Council and the Mayor to do so as the press will actually want something more than a statement.”

“We need to issue educational comms like a PlaniFax style video showcasing what we've done—which is a lot!” said Lovelace. “To paraphrase the famous movie scene—‘show me the units,’” said Mason, asking for proof that something would be offered to those evicted from crisis shelters.

“Remember, we are providing options far better than to have human beings living in sheds like animals.”

On July 9, four days before the July 13 given removal date, there was an attempt “to remove a number of vacated shelters.” By going ahead with its plan ahead of the July 13 deadline, the city triggered another wave of backlash from the public. Compounding matters, HMA also claimed that city workers had removed structures that people were currently living in. The situation gave rise to another wave of emails among councillors that day.

Austin asked whether the city was “100% certain that the shelters removed today were both unoccupied?” Acting CAO Kelly Denty confirmed that she’d checked with staff, who said the structures were locked with no possessions inside. “My only suggested update to the ops plan going forward is that staff should take pictures with a time stamp on them of ‘empty structure,’” said Mason.

“I do not want to turn this into a finger pointing session, but this issue is not going to go away,” said Outhit. “We are losing the communication and education battle to the folks that put up the shelters. We should use this as an opportunity to address an issue that is obviously very important to many. I have never received this amount of email previously on any topic. I feel we owe this to our residents.”

The mayor’s chief of staff, Shaune MacKinlay, pointed out that Haligonians were ready to respond if HRM continued removing crisis shelters. “Mutual Aid's Instagram is saying they have a ‘rapid response strategy’ and will announce a call out to community to protect the sheds,” she told the group.

Councillor Patty Cuttell said she was “really hoping we can discuss this more, as moving forward we need better solutions—not just for the people affected, but for our PR as well.”

But not all councillors were levelheaded. Lovelace got into the debate with one resident who emailed in support of shelters. “Is this where we're going as a city? Permitting (enabling) illegal drug and alcohol activity in our parks and not providing addictions support to those with substance use illness?” she replied. “HRM is not in the business of health care.”

Around 6:30 that night, Russell sent a note. “I've been quiet on this one because I've been too busy responding to e-mails about us being the worst people in the world,” he wrote to a variety of councillors and city staff. “We told people that we were removing the shelters on the 13th. Fine. We'll be given grief about that, and when it happens they might amass an army of protestors, but at least we will do what we said.

“Then we start removing shelters on the 9th ... four days early. It doesn't matter whether or not they were empty. No wonder people are pissed. How was the decision made for the shelters to be torn down, four days before we said that we were going to do that?”

Five minutes later according to the timestamp on the message, mayor Mike Savage replied to Russell alone, nobody else CC’ed on the email. “Just between us. We set a deadline of the 13th. It was never the intent that we wait til then and take them all down. It was clearly said yesterday that we would give notices and take them down as we could. If we wait til the 13 and then do it, we would provoke a confrontation that would potentially have dire consequences.

“Remember,” the mayor said, “we are providing options far better than to have human beings living in sheds like animals. Nobody should have to live in a shed.”

One minute before 10pm, Russell wrote back to Savage. “Agreed, and I see that side of it,” Russell said, although he still wasn’t happy about the dates changing. “This screams of bad planning, and we're on the crappy end of that stick. [redacted] When was the decision made for them to be done today? Why weren’t we told, yesterday?”

If Savage replied, it’s not included in the package of documents. But the package does have an email from acting CAO Denty sent the day before—at 9:14pm on July 8—addressed to the mayor and councillors. “In advance of efforts to remove a number of vacated shelters tomorrow,” Denty wrote, “I am attaching an updated Key Messaging and Q&A document for your reference.”

The first question is: “Why is the municipality removing some shelters before the deadline date of July 13?” The answer is that if any “current shelter occupants accept a housing option or temporary accommodation before July 13, the municipality will take steps to remove the vacant shelter.”

“HRM doesn't have a lot in common with LA, but we do have unhoused people and containers”

Things were calm for a few weeks, until August 18. The city was abuzz with the Halifax Pride Festival, and the Spring Garden Road concrete radiated heat into the humid air. After early-morning evictions at other parks, a crowd began to gather mid-morning at the old Memorial Library grounds. By dinner time, two wooden structures had been taken apart with chainsaws, 24 people had been arrested, a child pepper-sprayed and several people were rendered homeless.

As The Coast reported in November 2021, councillors were told about the event as early as August 3. The city’s response to the shelter siege was measured and exact. Nobody on city staff stepped out of line.

Potential solutions soon began to swirl about. The city was at the centre of controversy and needed a solution, quick.

Modular units were actually first suggested by councillor Kathryn Morse a week before August 18. “I see in Los Angeles they recently built homes for the unhoused out of shipping containers,” she wrote in an email. “I know HRM doesn't have a lot in common with LA, but we do have unhoused people and containers.”

CAO Dubé replied that the city was considering this but was “many months away from a recommendation as to whether HRM should build these.”

“A significant challenge is where such units might be located,” Dubé said. “We currently have no suitable sites we own on the Halifax peninsula and in the Dartmouth area where demand is greatest.”

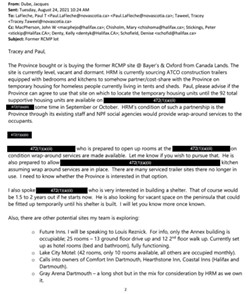

In the wake of August 18, other options were presented, too. On August 24, Dubé said he was looking into several things. He suggested using the former RCMP location on Bayers Road. “The site is currently level, vacant and dormant,” he pointed out, asking the province if it would be interested in a partnership. “HRM's condition of such a partnership is the Province through its existing staff and NPF social agencies would provide wrap-around services to the occupants.”

The CAO was also looking at Future Inns, the Lake City Motel, the Comfort Inn, the Hearthstone Inn and the Coastal Inn. Other organizations or people that reached out have their names redacted in the FOI. “[Redacted] is prepared to open up rooms at the [redacted],” Dubé said. “I also spoke [redacted] who is very interested in building a shelter. That of course would be 1.5 to 2 years out if he starts now. He is also looking for vacant space on the peninsula that could be fitted up temporarily until his shelter is built.”

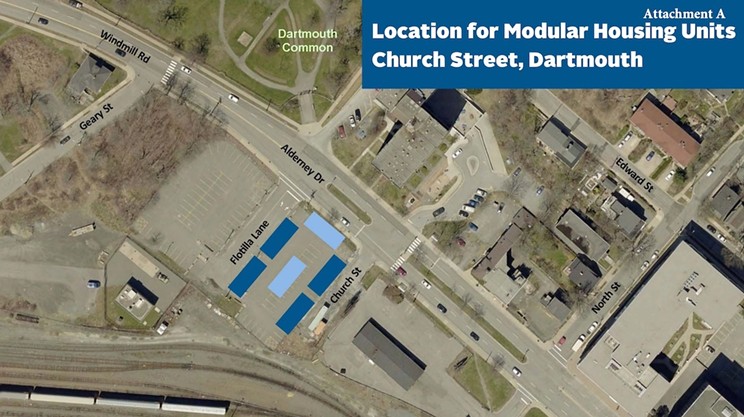

The CAO also mentioned the Alderney Road parking lot and Centennial Pool parking lot as potential modular unit lots in late August, as well as using the Gray Arena for housing, although at that point he called the Gray “a long shot but in the mix for consideration by HRM as we own it.”

Even landlords were considered. “I have spoken with many leading multi-residential property owners who are interested in exploring the amassing of up to 20-30 rental units dispersed across the City,” Dubé told councillors. “As long as the Province or HRM hold the head lease and the tenants can be removed immediately if they do something egregious.”

“The modulars are being purchased as I write this”

On August 26, mayoral chief of staff Shaune McKinlay created a draft motion that would authorize the CAO to spend up to $500,000 on housing. It would make its way through Dubé, to council, to be passed the following week.

Dubé told council this was “in anticipation of 90+ supportive housing units becoming available sometime this Fall.”

Enter the modular units.

In a September 23 email to the mayor, Dubé said he’d forwarded a partnership proposal to the provincial deputy minister of community services, Tracey Taweel, about sharing the cost on a set of modular housing units that were available for purchase. Savage replied, “these modular things are interesting” and Dubé called it “a quick win for HRM and the province.”

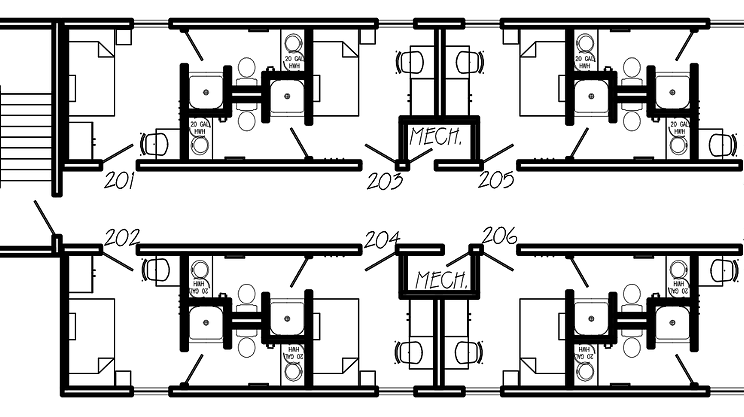

A few days later, on September 27, Dubé shared it with the rest of council. “We are in the process of acquiring a "work camp" comprised of 24 modules for $10,000 / module.”

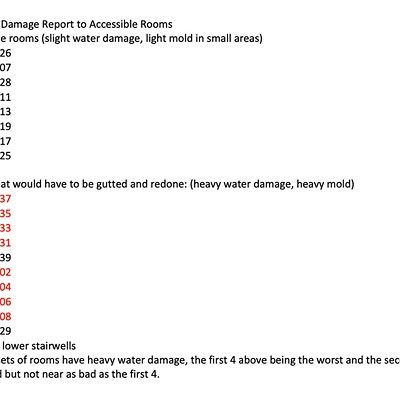

Dubé said there were “not a lot of changes needed to the good quality units” and that they had all been assessed “with about 1/2 of them in good shape.”

At the time, the CAO said the timing for getting the units ready could be “as little as one week, depending on finding the right company to partner with for setting them up and taking on needed renovations and site hookups to water and sewer.”

Dubé estimated renovations would cost less than $50,000, and the units were already in Nova Scotia.

“Replacement cost for a camp like this would be at least $2 million, and currently there is a waiting line of up to 2 years for new units,” he said. “So, these represent a great value to be able to turn them over into a quick, and warm place to live.”

The 73 units were only $240,000. The city acted quickly, and councillors were excited.

“Amazing work to secure the 24 modules and advance this project so quickly!” said Morse. Cuttell said, “this all sounds like it is moving in a positive direction. Amazing.”

“Just wanted to let you know how thoroughly impressed I am with your efforts and the amazing work done by staff and partners on this!” said Cleary.

Dubé told councillor Tony Mancini that people should be moved out of temporary housing at the Gray Arena “by the end of October assuming we have the modular units ready for occupancy. May be sooner but too many moving parts to deal with to commit to anything earlier.”

In late September, councillor Mason emailed the CAO about an apparent eviction planned for People’s Park—the unofficial name given to Meagher Park on Chebucto Road when people moved there after August 18. Mason was concerned that the eviction was maybe going to happen the next day.

“In order to regain trust, we need to first, before anything else, show we have solutions in place. Not announced. Not a future date. Done,” Mason said. “An eviction notice and removal of illegal and unsafe sheds will come in time, but forced removal of campers and infrastructure in Meagher and other sites cannot be our first move. Not only will this result in another violent confrontation, it will drive a wedge between us and the service providers.”

Dubé seemingly delayed the park eviction and assured Mason “the modulars are being purchased as I write this.”

On September 29, city staffer Erica Fleck announced the modular units publicly. For the next few weeks, councillors like Mason reassured residents that the modulars were on their way. “We also have modular housing purchased which should be set up in 2-3 weeks to move the remainder into,” Mason told one constituent in mid-October.

On October 21, the modulars purchase agreement came through from the province. Dubé said “good news” when he forwarded it to mayor Savage the next day.

But soon, someone on staff realized the units weren’t what they’d expected. The units had been through a flood, and the resulting damage and mould meant a full overhaul was needed. Councillors were informed of this on November 1 in an email labelled “PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL: not for sharing or dissemination in any form without the expressed consent of the CAO.” (Bolding, italics *and* underline in original.)

“I am writing to inform you that the modular units that we had committed to purchasing as alternative homeless accommodations were not as advertised by the vendor and require significant repairs not worth attempting,” wrote Dubé.

After a large redacted section, the note continued. “I was hopeful that we would have some modular units in place at Alderney by mid-November but now with this news, we are immediately trying to find other solutions,” said Dubé. “I apologize for this unfortunate situation but assure you that we are doing all we can to address it as we move forward with our plans to assist in providing crisis housing options.”

“This really bad news. Leaving aside the question of how we got this far before realizing the situation, we have made commitments to community,” replied mayor Savage. “Very disappointing.”

Councillor Mancini asked how soon he could share the information with residents, and was told by city hall staffer Sally Christie “you can share that you understand that there will be an update on Tuesday at Council but you have no details.”

Mason told Dubé that despite the error, “I know we can dig ourselves out of this hole we find ourselves in.”

The city tried to push the narrative the units were delayed for some mysterious reason, until a Coast investigation found them at a construction yard in Goodwood a week later. It was made public the following week at council.

“That is a crazy pile of money JD”

In need of a new strategy once again, city staff began searching for modular units that were a little less dilapidated. But that also meant more money would have to be spent.

“If any member of Council has contacts with potential suppliers, please send same to John MacPherson,” Dubé said on November 2. “Our procurement team continues to scour the region and country as well. What we need are units ready for occupancy similar to that shown in the drawings. They can be new or used and if the latter, they must not require substantial renovations. We have been and are looking at refitted shipping containers too.”

Offers also came in from the public, including one from Miawpukek Horizon Maritime Services Ltd.

“We have the Polar Prince in Mulgrave, with a skeleton crew on until it's drydocking in February, it has accommodations for 62 (likely 50 could be made available). I could make it available until first week of January if it helped,” said Richard McLellan in an email to the mayor in November 10. “The cost would be about $75,000 to move it to Halifax (and back in January), and a couple thousand a day (I'd have to confirm services costs alongside in Halifax).”

But in the end, everything came down to Jacques Dubé. In his original November 1 email, he mentioned four new buildings in Quebec that could accommodate 24 units and be delivered at a cost of $710,000.

“We are striving to have these installed by the end of November, assuming we are successful in finalizing the procurement of these units and preparing the site/utilities at Alderney,” he said. “In order to cause these new units to be shipped as soon as possible, it is my intent to proceed with this purchase today or tomorrow.”

As the original budget from council was only $500,000 (and $102,000 had already been spent, not including the $240,000 disputed price of the modular units), the CAO was officially over budget, and said he’d ask for an increase at the next meeting.

Councillors agreed it wasn’t in the cards to say no. “Given the urgency and importance of this issue, I can't imagine any of us objecting to purchasing alternative units and spending a little extra,” said councillor Cleary.

“How unfortunate the stress and pressure you must all feel. I have no objection to the overage on this occasion,” said Deagle-Gammon.

Those eventually became the 24 Dartmouth units. But once the Halifax units were added, and construction factored in, the total cost was nearly $3.2 million.

“That is a crazy pile of money JD. Is this something you are bringing to Council tomorrow? Man. That's very expensive,” the mayor replied. He was so shocked he sent a second message. “I had no idea we were looking at this kind of expenditure. Wish I was at the meeting to discuss. Will support what Council decides of course. Just a big price tag.”

After another debate at council, the spend was approved. The new units would reportedly be complete before the new year. They wouldn’t.

The modulars open at last

Finally, in mid-January, the Dartmouth modular units opened, run by Out of the Cold Shelter, and 24 people moved in. And last week people started moving into the nine units—able to accommodate 38 people—in Halifax. It was a long 10 months, from councillor Morse first suggesting modular housing in August 2021 until the Halifax site was finished, to help a fraction of the city’s houseless population.

Many unhoused residents are still living in crisis shelters or tents in public parks. And HRM still doesn’t want them there.

People’s Park has drawn particular attention. “We’ll clean up the park and we would allow everybody to have access to it again,” mayor Savage told The Coast in March 2022. People’s Park is not one of the four park sites that councillors unanimously approved for tenting at this week’s council meeting.

And after all that hard work, a few weeks ago Halifax CAO Jacques Dubé announced his resignation. He’ll stay at a city hall until the end of 2022, and then? Halifax might change its messaging around homelessness again next year.