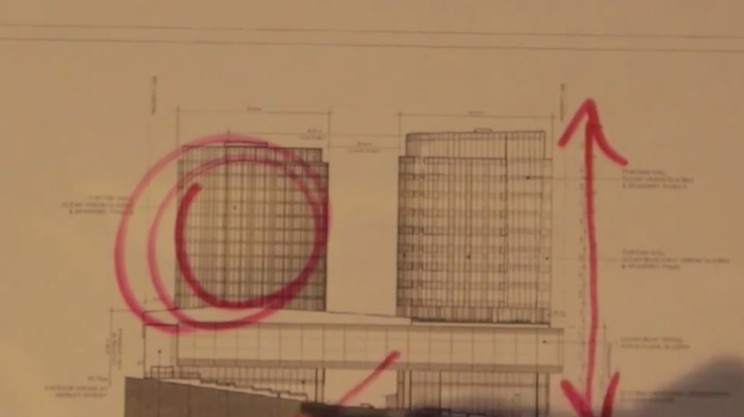

The Nova Centre now under construction downtown is by far the largest development project in Halifax history. Revised plans for the project submitted by developer Joe Ramia's company, Rank, Inc., show two towers for the site–a 17-storey hotel facing Market and Prince Streets, and an office tower along Argyle Street, consisting of two connected bulbs, one 15 storeys, the other 14 storeys.

Three floors of the towers will be devoted to the new publicly financed convention centre, and will stretch over Grafton Street, which will become a private driveway into the complex from Prince Street. The convention centre will also extend away from the towers, to the corner of Sackville and Market Streets, allowing the creation of a large, column-free ballroom space. The ground floors of the structures will be occupied by restaurants and other retail uses. All told, Nova Centre will consist of over a million square feet of usable space. In comparison, Halifax's next largest development project was the three-building Purdy's Wharf complex, which totals about 700,000 square feet.

Construction costs for the entire project were reportedly $500 million a few years ago; undoubtedly that figure has increased. The three levels of government are paying $163.4 million for construction of the convention centre portion of the project, but most of those costs will be amortized; added to operating and maintenance costs paid to Rank, they will amount to $332.5 million over the next 25 years. Throw in a few 10s of millions for associated costs like the rehab of the existing convention centre into something useful, and we're talking real money.

However we price it, there's no question that Nova Centre is an ambitious project. But what does it say about us as a city?

"Giant buildings are tied to the character of their creators...the demonstration on a grand scale of an organization's essence," writes Edward Tenner in his 2001 essay "The Xanadu Effect." "Xanadu, you may recall, was the palatial centerpiece of Orson Welles' Citizen Kane, the brilliantly unfair film biography of William Randolph Hearst," says Tenner. Xanadu was the cinematic counterpart to the real-life Hearst Castle, a 24,000-acre "ranch" near San Simeon, California. Hearst had spared no expense on the castle, which consisted of four buildings with 165 rooms, the 354,000-gallon Neptune Pool, built in the style of a Roman temple, a movie theatre, the world's largest private zoo, an airstrip and every comfort imaginable. The expense of the castle eventually bankrupted Hearst.

Tenner, a historian of technology, notes that many giant buildings are the physical manifestation of financial overreach and "overweening egos." He lists a baker's dozen: The expense of St. Peter's Basilica and Versailles presaged the Reformation and French revolution, respectively; Nazi architect Albert Speer's plans for an 180,000-seat Great Assembly Hall and Ceaucescu's 2,000-room "House of the People" in Romania tell obvious morality tales.

In the US, the Singer and Metropolitan Life buildings arose just before the depression of 1907-1910; 40 Wall Street, the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building as the Great Depression was unfolding. The World Trade Centre and Chicago's Sears Tower coincided with the energy crisis of the 1970s. The Houston skyline was constructed mostly just before the 1980s collapse of OPEC, and many of the buildings remained empty through the 1990s. Marketsite Tower, the $37 million Nasdaq tower studded with 18 million light-emitting diodes overlooking Times Square, opened mere weeks before the tech bubble popped in 2000.

There are counter-examples. "The construction of the Mormon Temple in Washington actually mobilized the community, and the act of fundraising helped create the community," says Tenner over the phone from New Jersey. "And it's been theorized that the pyramids of ancient Egypt are not the product of the society of the pharaohs; the act of building them created that society." In his essay, Tenner says the US Capitol matched the soon-to-be realized aspirations of a wanna-be great power, and the Eiffel Tower became the symbol of renewed cultural and scientific vigour of France after the humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.

Which brings us back to the Nova Centre. Is it a classic case of financial overreach on the developer's part, like the litany of giant buildings Tenner enumerates? Is it emblematic of an overweening civic ego—a city so driven by desire to be a world player that it has thrown caution to the wind on a hopeless endeavour that will remain a monument to foolishness for decades to come?

Or, on the other hand, is Nova Centre transformative, the Nova Scotia version of the Mormon Temple? Is the very act of executing the planning and financing marking a fundamental change in how we go about business?

Ross Cantwell and Greg Brewster are among the most knowledgeable people in Halifax in terms of understanding the real estate market for office space. Cantwell has his own firm, Cantwell & company, and studies the "macro" side of the industry—overall global trends. Brewster is VP for office leasing at Colliers International and studies the "micro" side—how those global trends play out in Halifax. Both men consult for companies large and small, including for Ramia's Rank, Inc. So we asked them: Is Ramia over-reaching? What are his prospects of finding tenants for the new building?

"Not very good," answers Brewster.

Cantwell explains that there are structural changes in the market for office space, and especially for the top-rated office space of Nova Centre. Most of that "Class A" space goes to the so-called FIRE industries–financial, insurance and real estate companies– with additional demand in downtown Halifax for legal offices, due to the proximity to the courts.

But for those industries, the office space needed per-employee has plummeted. "In the '70s and '80s, it was 300 square feet per employee," says Cantwell. "That number has been dropping slowly. It went to 225, and now to 175 and some firms are dropping it down 125 square feet per employee.

"Look at KPMG, moving out of Purdy's Wharf into RBC Waterside," continues Cantwell. "They're reducing their footprint by 40 percent. They're going from 10,000 square feet in Purdy's to 6,000 square feet in Waterside, with the same number of employees."

At the same time, however, Halifax has recently seen an explosion in new office construction, because the bulk of the old office stock downtown is inefficient and too big for most companies' needs. The result is a big increase in vacancy rates, and decreasing rents.

Both Cantwell and Brewster praise the Ramia family, which owns Rank, for their business acumen. And Joe Ramia seems to sincerely want to do something large and spectacular that's good for the city. But good intentions do not make a successful project.

Cantwell thinks Ramia is trying to entice BMO to move its offices up the hill from George Street to Nova Centre, but Brewster says even if Ramia is successful, it's not enough–the bank's decreasing need for office space isn't enough by itself to make Nova Centre viable.

That leaves the possibility of a firm from outside the province moving into Nova Centre. "The Ramias keep talking about being tapped into the international high finance world, but world financial markets are not that strong," says Brewster. "I have heard nothing about any real, solid prospects."

So, is Joe Ramia building a monument to his own unrealizable ambition? Is the Nova Centre his Xanadu?

Probably not, says Brewster. "He's had some pretty good flexibility in the past. How many other developers would be able to build the basement and not the building? Honestly, leave it right there." Brewster is referring to city council's recent vote to allow Ramia to build the underground portions of Nova Centre without any development permits in place for the above-ground parts—a procedural loophole never given to any other developer.

"It's very easy to leave it unfinished," continues Brewster. You say, 'Sorry guys, we tried, and didn't quite make it, but look what we've done already.'"

Brewster isn't exactly predicting it, but he's suggesting we may very well end up with a Nova Centre that has no office tower.

Ramia is a private businessperson, free to speculate and succeed or fail as his skills and fate may have it. That normally wouldn't be any of the public's concern. But Nova Centre is so intertwined with government tax expenditures–and tax collection–that it becomes impossible to separate the two.

For example, when Halifax council considered the deal with Ramia, it was presented with a report listing the potential for $3.8 million annually in new tax revenue that would be generated by Nova Centre, with about a third of it, $1.2 million, coming from the office tower.

"The funding strategy for the Municipality's share of the [convention centre] costs," reads another report to council (page 4), "is to direct taxes from the entire convention centre site to a reserve, and to pay for HRM's share of the lease and operating costs from this reserve."

The city's share of lease and operating costs is $2.9 million annually, with an additional $5.2 million annually in amortized construction costs, for a total of $8.1 million a year. On the revenue side, the Nova Centre site is expected to bring in just $3.8 million annually, for a loss of $4.3 million every year. Take away the expected $1.2 million in new taxes because the office building isn't built, and the deal starts looking even more dicey.

The original Xanadu was the summer palace of Kublai Khan, the emperor of China, in the hills of Inner Mongolia. Marco Polo wrote about Xanadu in the 13th century, describing a well-maintained garden in which the emperor had erected a portable residence built out of bamboo, and so fragile that it it was held together by silk cord, lest the wind blow it down.

Four centuries later, the English clergyman Samuel Purchas wrote about the place, but described the portable residence as a "sumptuous house of pleasure." Nearly 200 years later, in 1797, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was reading Purchas' book and, while tripping on opium, wrote his poem "Kublai Khan," transforming the residence into a "stately pleasure dome."

At each retelling, Xanadu becomes grander, more beautiful, more fabulous. Similarly, the benefits of the convention centre become more fabulous at each retelling, and now we've reached the point where backers, like Coleridge before them, appear to be in a drug-induced euphoria. The convention centre will be a success, they tell us, because more people will visit here on business trips, discover the joys of Nova Scotia, bring their families back to vacation and spend, spend, spend. They'll like the place so much, they'll move their companies here, and we'll all be happily employed forever after.

When Peter MacKay announced federal funding for the convention centre, he assured us the project was the transformative sort of Xanadu—it would, he said, "take the 'no' out of Nova Scotia," alluding to an alleged culture of defeat that keeps us from reaching our full potential, which amazingly exactly coincides with the desires of the business classes.

But in the sober world of reality, there's good reason to think the convention centre will be that other sort of Xanadu–a monument to unrestrained ego and untempered ambition.

Convention centres across Canada are failing to meet the projected delegate counts forecasted for them. The most famed Canadian convention centre is Vancouver's, which was rebuilt and expanded for a grand reopening timed to coincide with the 2010 winter Olympics.

"It was a colossally expensive project," says Charlie Smith, the editor of the Georgia Straight, who has followed the project from its inception. "It's Vancouver's Palace of Versailles," he says, unknowingly comparing the VCC to one of Tenner's examples for the Xanadu Effect.

PAVCO, the provincial crown corporation that runs the VCC, had hired consultants to make projections for the number of out-of town delegates who would attend conventions. The projections, says Smith, "didn't bear any similarity to reality as it unfolded."

The most recent Tourism BC report on the VCC lists 208,790 "non-resident delegate days" for the first three quarters of 2013. This represents a 43 percent drop from the 364,726 non-resident delegate days for the same period in 2012.

And in Ontario, the city of Kingston has been thinking about building a convention centre, and so recently hired HLT Advisory. In 2009, HLT was one of the consultants that recommended Halifax move forward with its new convention centre, but five years later, the company is notably less bullish.

"Some new centres," reads HLT's report to the Kingston city council, "are struggling (ie, Scotiabank Convention Centre in Niagara Falls opened in 2011 and is experiencing low demand and is using it for different uses than initially intended) while the control of some older centres (eg, Hamilton Convention Centre) has been ceded to private operators (who have contributed very limited capital). The oversupply situation is not unique to Ontario."

But "Halifax is different," say convention centre advocates, and seemingly nothing will dissuade them. People who are skeptical about the alleged benefits of the convention centre are vilified as "naysayers," as enemies of progress.

"In the 1920s' United States, there was this booster mentality that was satirized by novelists," says Tenner, mentioning Sinclair Lewis' Babbitt. "I think that although people have become in some ways more sophisticated, and rhetorically different, the psychology of boosterism hasn't changed that much. The idea is that somebody who is expressing doubt is bringing in a negative energy, and so there is a very powerful social bias against any kind of skepticism as something that breaks the spell of confidence that is essential to the enterprise.

"You don't find that in all environments," he continues. "In military planning, there's always a faction of generals or other officers who question whatever plan you have, and you have to persuade them. The difference is that in the booster mentality, any kind of skepticism is thought to be disloyalty to the team."

There is yet another Xanadu–the Olivia Newton-John film, a spectacular flop that inspired the creation of the Golden Raspberry Awards.

The film is bad in all the wrong ways. It's not purposefully bad like Sharknado or Troll 2, and it doesn't rise to the level of camp, like Barbarella or Showgirls. Xanadu is just plain bad.Xanadu is an absurd tale of about a mythical being, a Muse, becoming real through the power of true love, and disco. "And now, open your eyes and see," sings Newton- John. "What we have made is real. We are in Xanadu. A dream of it, we offer you."

She could just as easily have been singing about our new convention centre, a dream made real. And here it rises before us, our very own Xanadu.

The incredible shrinking convention centre

When it looked like the political stars were aligning to pay for a new convention centre, Trade Centre Limited had to get serious about justifying the expense. TCL hired Criterion Communication, a Vancouver firm, to produce a Phase 1 Report of the potential demand for a convention centre.

"A preliminary estimate based on the apparent business opportunity and comparisons with other Canadian centres suggests that a [Halifax] facility designed to accommodate 1,800 to 2,000 delegates and configured to be able to efficiently manage multiple, simultaneous events would be justified," reads the Criterion report. "In general terms this would roughly equate to a facility of between 150,000 and 170,000 square feet of rentable function space comprising a combination of exhibition/multi-purpose space and meeting, ballroom and pre-function spaces."

The Criterion study was held up as proof that a new convention centre was worth the cost. But a funny thing happened as the convention centre proposal was honed down to specifics: the 150,000- to 170,000-square foot convention centre envisioned by Criterion got whittled down to a mere 120,000 square feet. The smaller size was apparently arrived at because of the space restrictions for the site proposed by developer Joe Ramia on the blocks once occupied by the Chronicle-Herald and Midtown Tavern buildings.

Criterion's idea was for a convention centre 25 to 42 percent bigger than the one we'd get. But when TCL paid for five more consultant reports to estimate potential delegate counts and economic impact from the proposed convention centre, the consultants all built from Criterion's original proposal for a 150,000 to 170,000 square foot centre, and not from the reality of a 120,000 square foot one.

Halifax firm Gardner Pinfold was hired in 2009 to discover the economic impact of the new convention centre, it noted that "actual impacts associated with the facility will correspond to what is actually built. [...] The net usage space would be about 150,000 square feet." At that size convention centre, said Gardner Pinford, direct and spinoff economic impact from visiting delegates would be $15.6 million annually (page 21).

Even then, TCL rejected the consultants' reports and did its own in-house calculation of predicted delegates, wildly inflating the numbers from consultants' predictions, and sent the new numbers back for a second round of economic impact forecasting. It's no surprise that with higher numbers of delegates, the supposed economic impact increased–a second, "supplementary" report prepared by Gardner Pinford in 2010 put the "revised" economic impact from visiting delegates at $22 million annually, a 41 percent increase from Gardner Pinford's first report. Those new, higher numbers have been the numbers used in all subsequent discussion of the convention centre.

While the consultants were calculating economic impact based on a 150,000 square foot convention centre, on October 1, 2009 the province issued tender offer No. 60138662 for a convention centre with 120,000 square feet of usable space (not including hallways, kitchens, washrooms, loading docks, etc). That was to consist of a column-free ballroom of 35,000 square feet, 50,000 square feet for exhibition space and 35,000 square feet for meeting rooms. On July 19, 2010, the tender was awarded to Rank, Inc., the only eligible bidder.

But TCL is advertising an even smaller convention centre on its halifax2016.ca website. "Nova Scotia's new Halifax Convention Centre offers over 120,000 square feet of flexible space in the heart of downtown, including a spectacular 30,000-plus square-foot ballroom overlooking the city and 40,000 feet of exhibit space," states the site. And while the floor plans on the site don't detail dimensions, it appears the "120,000 square feet of flexible space" includes hallways and the like–comparing the plans to Rank's revised submission to the city for Nova Centre reveals usuable space in the convention centre at about 105,000 square feet total.

How is it possible that TCL's advertisements and floor plans both show convention centre spaces considerably smaller than those required by the tender awarded to Rank?

We asked the Department of Infrastructure that question, and a spokesperson referred us to TCL. We then called TCL, and spokesperson Suzanne Fougere told us that "the floor plans on our site aren't to scale." But, we asked, how can you advertise a convention centre that has a ballroom and exhibit space smaller than that specifically required by the tender? Fougere referred us back to the Department of Infrastructure. —TB