There’s a fascinating way in which movies shape our view of the world. And it’s not in the more common toxic ways most people are familiar with, like romantic comedies teaching generations of men that stalking is the most romantic thing they can do to woo a woman. Nor is it the subtle racism taught by movies, like using yellow filters in non-white countries to make the white actors stand out more compared to their non-white counterparts. Or the not subtle racism of movies like Independence Day, which portrayed individual Western countries taking out alien spaceships, and the continent of Africa was represented like this:

Even though, in the year that movie is set, the South African Air Force was flying these:

No, in the Halifax Regional Municipality, the most dangerous Hollywood trope is the expectation of a happy ending. Our collective desperation for the fires in Nova Scotia to end happily makes the lives of emergency responders a little bit harder. Because in our heart of hearts—when we heard that the fire in Tantallon was 50% contained, when we heard that the Dairy Lane fire was 80% contained, when we saw rain in the forecast—optimism settled in. But optimism leads us to take risks that we don’t see as risks—like taking a bike ride on the Shearwater Flyer Trail, which is nowhere close to Tantallon.

Emergency management officials don’t buy into Hollywood tropes and expectations in the same way normal people do. They plan as though the worst that can happen will happen, and make rules accordingly. It’s hard for people who don’t live in the world of risk assessment to understand what professional emergency responders are factoring into their decision-making. From profit motives to disaster preparedness to municipal planning, there are a lot of variables affecting and exacerbating the climate emergency, which explains some of the seemingly arbitrary rules emergency responders are asking us to follow. To help contextualize why emergency responders are making the decisions they are, we’re going to try and explain some of the wildcards that exacerbated the climate emergency that firefighters were considering when responding to the fire in Tantallon.

Wildcard number 1: The profit motivation of capitalism (AKA the invisible hand of the market)

One of the ways capitalism is making fires worse in Canada is that Boreal forests are now more prone to fire. John Vaillant, author of Fire Weather: the making of a Beast, writes that climate-change-induced fires will become more common. As the world heats up, we get less rain and less snow, meaning fuel in forests dries out faster in the hot spring and summer months. For Nova Scotia, there’s an additional risk of climate-change-induced forest fires due to the closure of the Northern Pulp mill.

In Nova Scotia, Boreal forests have historically been limited to Cape Breton, with coastal areas being a mix of Acadian and Boreal forest types. Healthy Boreal forests are supposed to burn every 60 to 150 years, and until European colonists showed up, Indigenous peoples had Boreal fire management down to a science. We don’t do that anymore. Instead, in 2018 the provincial government got the Lahey report. The issue with Lahey’s study, as reported by The Coast in 2018, is that a lot of the recommendations were to increase private forest management and limit public forest management. The Ecology Action Centre also pointed out that the Lahey Report suffered from a form of regulatory capture, with the EAC characterizing Lahey’s proposed triad model as coming “straight out of the industry’s mouth.”

And that focus on industry and profitability ahead of the environment has led to a capitalism-weakened forest. “Nova Scotia’s old-growth forests have, over the past several decades, been largely transformed into pulp plantations for international corporations. Sixty years ago, before the pulp mills in Pictou and Port Hawkesbury went into operation, 80-year-old trees covered a quarter of the forest canopy,” wrote Jacob Boon in The Coast in 2018.

What has been happening is the Nova Scotia wood industry has been working hard to convert the Acadian forest into a more flammable Boreal forest because it’s more profitable. And the Borealization of Acadian forests is not equal. Since it’s being done for profit, it has created patches of softwood forest and patches of hardwood forest, decreasing the biodiversity and resilience overall. Or as the president of Nature Nova Scotia, Bob Bancroft, wrote in 2020 describing industry practices: “The resulting treatments leave too little forest for wildlife to survive. They often fail to promote the regeneration of valuable tree species. But they perpetuate all the major deleterious clearcut effects, which include sun-exposed soils, dryness, increased temperatures with tree shade removed, hit-and-run rains in brooks, causing wildly fluctuating water levels in streams, and major nutrient losses in soils.”

(Funny story about the word “Borealization.” In 2018, Dr. Tom Beckley, the not-yet-author of the Borealization study, did an interview on CBC Radio in New Brunswick and had the temerity to say the word “Borealization” on the air. The power-mad J.D. Irving group of companies called Beckley’s boss at the University of New Brunswick. They said Beckley had made up a word that made them look bad and that Borealization wasn’t a real thing. The Halifax Examiner asked JDI about why they tried to narc Beckley out to his boss. Jason Limongelli, vice-president of woodlands for JDI, wrote to the Examiner, saying in part: “Dr. Beckley used the term ‘Borealization’ during the CBC interview in March 2018. This is not a term that we are familiar with as trained foresters and as of this writing we are not aware of any peer reviewed science that demonstrates ‘Borealization” of Acadian forests.” Then, in one of the most legendary academic “stickin’ it to The Man” moves in recorded history, Beckley wrote a study proving the Acadian forest has been Borealized.)

In 2016, when the provincial government decided to go ahead with cleaning up Boat Harbour, the forestry industry knew it would need new markets for low-quality wood. There are a lot of uses for low-grade wood, like making compressed wood products for home construction or burning it for energy. And since there are other uses for low-grade wood, the provincial Liberal government got to work and, in 2019, identified over 100 buildings that could be converted to biomass heat. If that had happened, there would be a larger market for low-grade wood.

Converting to biomass heating is controversial. On one side, there’s Stephen Moore, the executive director at Forest Nova Scotia, saying it would get Nova Scotia 20% of the way to its climate goals. On the other hand, professor John Sterman of MIT argues that burning biomass will actually increase the speed at which the climate emergency perpetuates the extinction of humanity. We still don’t really know which one of those two theories is correct, because even though the government decided to convert those 100 buildings in 2019, only six have so far been converted. And those six were delayed by the use of public-private partnerships.

Moore blames the delay on the government practice of “unicorn hunting.” Unicorn hunting, in this case, doesn’t mean trying to find the perfect addition to a threesome, nor is it the highly regulated hunt of mythical animals at Lake Superior State University. No, it’s the government practice of dumping millions of dollars into unproven technology of dubious merit. Moore points to the $50 million provincial Forest Industry Trust, which he says is mostly being wasted on unicorn hunts that aren’t really delivering any tangible good.

Moore finds himself disagreeing with environmental activists these days, and doesn’t think the forestry industry and environmental activists should actually be at odds. He says they both want a healthy forest, and there are debates the industry and environmental activists should be having—like whether his view on clearcutting is compatible with healthy forest management. Instead of working with activists for a healthy forest, he finds himself fighting them instead. He laments the soured relationships, which he blames in large part on governmental reliance on formal communication (AKA stakeholder engagement), which has also degraded the communication between industry and activism.

On top of all of that, after Hurricane Juan in 2003 there were three paper mills operating, so there were a lot of people interested in buying downed trees, and there were enough woodlot owners and forestry workers to make for a relatively quick cleanup. Last year when Fiona hit, there were no operational pulp mills, and the forestry sector in Nova Scotia had shrunk to reflect that. In an October 2022 interview with SaltWire, Todd Burgess of Forest Nova Scotia said, “The biggest concern that the forest sector has right now is our capacity to harvest, it is about half of when we had Juan.” Later in the story, Scott Tingley with the Department of Natural Resources is quoted. “All those dying trees will contribute to what we call the fuel load,” he explained. “Anytime you increase the fuel load, there's potential for increased intensity in the fires.”

In order to burn, fire needs oxygen, heat, fuel and a sustainable chain reaction. Oxygen is plentiful (obviously), and thanks to the profit motive of capitalism (as explained above) heat and fuel are abundant in Nova Scotia’s forests. This is why winds are so dangerous on hot days. Winds can carry chain reactions, in the form of embers, into new pockets of fuel, heat and oxygen. That’s why firefighters insisted, even as they started to contain the HRM fires, that any ember that escaped the boundary was an extreme risk of igniting a brand new fire.

To Moore, the scariest part of the already extreme fire season in Nova Scotia is that most of the areas with Fiona-downed trees have not been cleared and have not yet burned. It’s a provincewide fire apocalypse just waiting for the right weather conditions.

The last factor in the profit motive wildcard is flammable housing. Housing is an extremely profitable industry, so in an effort to maximize profit, modern homes and most of their contents are manufactured with extremely flammable petrochemicals. Fifty years ago, houses took 30 minutes to burn. Thanks to the proliferation of oil-based construction materials and petrochemical-laden household consumer goods, a modern home burns in little as three minutes. And every room in a modern home is its own East Palestine rail derailment toxic cloud waiting to happen. Modern homes wrapped in vinyl siding ignite quite easily and quickly become death traps because of errant embers.

Wildcard number 2: Poor political leadership

On aggregate, the Canadian political class is a group of short-sighted idiots who don’t plan for our long-term future because it would be bad for their own self-interested immediate political future. And that means we don’t prepare for disasters, so we’re never ready for disasters. This is why the HRM was not ready for the Tantallon fires, even though city staff warned council of the danger in 2003. But we’ll come back to that later. For now, a stop in 2010 at Dalhousie University to talk about family doctors. In 2010, it was just after the H1N1 virus of 2009 and Dalhousie was hosting a conference of the Canadian Institute of Planners, chaired by a man named Kevin Quigley.

At that conference, Nova Scotia’s chief public health officer Dr. Robert Strang gave a lunchtime address. According to the scribe of the presentation, Eric Snow, Strang told the audience he had learned the following lessons from the H1N1 crisis he had just dealt with in 2009: He told the audience that since governments needed vaccines, Canadian governments learned that they needed to be able to make vaccines in Canada.

In 2020 when COVID hit, the lesson identified by Strang had not been learned by the Canadian political leadership class. That’s why the federal government scrambled to buy $9 billion worth of vaccines. Because it was a scrambled, unplanned purchase, Canada paid way too much and has ended up throwing out over 24 million doses so far. And barring any change between now and December, $1 billion of public money will be quite literally thrown straight into the garbage by the end of the year.

The federal government, to its credit, belatedly realized this was a hole in Canadian disaster preparedness and decided to create a Canadian biomanufacturing facility that could make vaccines. But then, proving that governments fundamentally don’t understand disaster preparedness, once the feds built the biologics manufacturing centre with public money in 2022, it immediately turned it into a public-private partnership.

In 2010, Strang also told the audience that family doctors were crucial in getting people to trust and take the vaccines, so the Canadian health-care system would need to focus on family doctors in the future to help prevent the spread of new pandemics. The family care shortage Strang mentioned in 2010 was a crisis in 2020, and was not helpful in preventing the spread of COVID. But if Strang pointed this out in 2010, and politicians have been enacting policies to fix it for the past 10 years, what has gone wrong?

While it’s true that Dr. Strang (and other highly qualified experts) advise governments on their fields of expertise, it is ultimately up to politicians what to do with that information. There is a family doctor shortage, so Nova Scotia premier Tim Houston decides to spend $5 million on training new doctors, and it seems like he’s doing a good thing. Former premier Stephen McNeil also trained new doctors and his successor Iain Rankin promised the same thing. So why hasn’t it worked?

The fact that McNeil decided to revamp the health-care system without talking to doctors might have something to do with it. But more likely, the reason we don’t have more family doctors is because our politicians aren’t taking the time to understand the problem. The number of physicians being trained in Canada is on the rise, but they aren’t becoming family doctors because, as the CBC reported two months ago, the Canadian medical school system sets family doctors up to fail.

It’s unclear why the provincial government persists in spending money on policies that won’t help our health-care crisis or make our province more resilient to disasters. To better understand the political choices being made, The Coast requested an interview with Dr. Strang to get more information about what advice he had passed on to politicians about the H1N1 pandemic. The Coast told the province we’d be willing to wait for an interview for this piece, especially because we asked for a long interview: 20 minutes. But “unfortunately, we are not able to accommodate your request for an interview at this time,” wrote a government spokesperson in an email.

In fairness, it’s hard to accommodate a long interview for people in Dr. Strang’s position.

In cynicism, the provincial government controls access to Dr. Strang, and it is possible that his answers would make our politicians look really bad, so maybe he wasn’t allowed to speak. The practice of muzzling scientists has become quite popular in recent years.

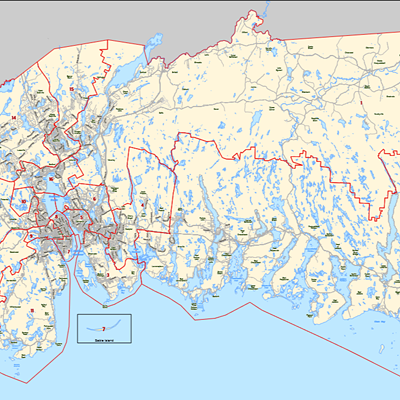

Going back to Kevin Quigley, the host of the conference and the co-author of Too Critical to Fail: How Canada Manages Threats to Critical Infrastructure. He is one of Halifax’s foremost disaster experts. He spends a lot of his time imagining how things can go wrong to gauge if we’re ready. In 2017, he and his team created a computer game to see how quickly Halifax could evacuate in an emergency if it needed to. He found that the city’s five main choke points and reliance on cars mean that a full evacuation would take at least 15 hours. “In (the) Halifax peninsula we have only five exit and entry points, so it poses, in a way, a serious threat to the transport network itself,” he told the CBC in 2017. Apologies to anyone who understands our current car dependency who watched some of those harrowing videos of people escaping the wildfires for your impending nightmares of being trapped.

But the reliance on those five chokepoints is somehow worse. In an interview with Signal Radio in 2018, Quigley also pointed out that Nova Scotia’s disaster management suffers from a Swiss cheese problem. A lot of Nova Scotia’s emergency preparedness assumes that no other area will have an emergency at the same time. Quigley pointed out that most towns and cities in this province make the planning assumption that, if they have to evacuate everyone, all of Nova Scotia’s buses will be available for use. But what happens if Truro and Halifax both need all of Nova Scotia’s buses to evacuate at one time? There aren’t enough, never mind that they'd be stuck in traffic leaving Halifax.

A similar issue exists with fire resources. Deputy fire chief Dave Meldrum told gathered reporters on the morning of June 1 that HRM’s firefighting resources were “stretched, but holding.” In a phone interview after the fact, The Coast asked Department of Natural Resources forestry technician David Steeves about the strain on the HRM’s fire services, asking if emergency crews would have been able to handle an additional fire at the peak of the wildfires on Sunday, May 28, or when the Waeg was burning on the afternoon of June 1. Steeves said they would have requested any resources that were needed to deal with additional fires. A few hours after the Waeg had started burning, the province put out an emergency notice for able-bodied firefighters at the request of DNR.

— Halifax Fire News (@HRMFireNews) June 1, 2023

We’re short doctors, we’re short firefighters and, as we learned when Tantallon burned, our subdivisions also don’t have enough emergency exits. On June 6, council met and passed a motion from councillor Pam Lovelace to figure out how to put emergency exits into subdivisions that could or would need them at the start of a fire. During the debate, councillors from around the HRM told each other that many subdivisions in their district also only have one entrance or exit. And even though we have an example from not even two weeks ago that only one exit is a death trap; and even though the risk of wildfires engulfing subdivisions around the HRM is still really high; and even though you are in danger of dying in a fire due to not having an exit to your subdivision right now; your councillors made the political decision to wait for December for a report before they even start considering helping you be prepared for the wildfires that could trap and kill you in your subdivision as early as next week.

And it’s not like this risk is a surprise to the city. David Hendsbee told his fellow councillors that the HRM had learned about the risk posed by lack of fire egress in 2008 with the fire in Porter’s Lake. It’s also a lesson the HRM could have learned about the Indigo Shores subdivision on Jan. 16, 2003. They didn’t—because of wildcard number three.

Wildcard number 3: Municipal planning

“I find it amazing that we debate whether we need to build a new fire station or not,” said HRM councillor Patty Cuttell at the Jan.18 budget meeting. “Things like that shouldn’t be a political decision of council. It should be a safety standard.” Council was talking about adding a fire station to Bedford. The city can’t really afford to add the fire station to Bedford—it’s millions of dollars the city doesn’t really have because the suburbs are a car-dependant Ponzi scheme. On top of that, Halifax’s fire chief Ken Stuebing had just finished telling council that his department is plagued by the city’s invisible infrastructure deficit. In other words, the fire department doesn’t have enough fire infrastructure to keep the people of Halifax safe to the minimum fire safety standards in an emergency.

Virtually no resources available in the core now. Units are being tasked as quickly as they become available.

— Halifax Fire News (@HRMFireNews) June 1, 2023

The crux of the issue is this: City planning is functionally an exercise in how to manage the physical geography of the city of Halifax. Council has for decades allowed, encouraged or enforced a development pattern of low density, known as suburban sprawl. When cities are developed in this way, the tax base is spread out, and spread-out communities don’t raise enough tax revenue to sustain the municipal services they need, like fire safety. At many points, councils of the day could have stopped this massive public safety hazard from happening but ultimately decided not to.

It all started in 2003.

Shortly after amalgamation, the province and the city were figuring out how to create a plan for the whole of the HRM. The city and province were coming together to “make efficient use of municipal water supply and municipal wastewater disposal systems,” as well as to get some consistency between the province and the city “relating to drinking water, flood risk areas, agricultural land, infrastructure and housing.” And even then the provincial government warned the city that “past experience in HRM has shown that developers will undertake accelerated development approvals in order to pre-empt new growth management regulations. For example, more than 3,000 lots were created during the plan review process for the Hammonds Plains, Upper Sackville and Beaver Bank Plan Area, significantly undermining the original intent of the plan.”

The report then goes on to warn council that there are “25,000 acres of vacant land scattered throughout the rural commutershed which are owned by companies that have a development interest.” The report continues, “experience has shown that the landscape of HRM may not sustain large-scale developments with on-site services.” And then the report lists the following risks to the HRM if it screwed up this planning process:

- Increase in the frequency and severity of water quantity and quality problems related to un-serviced development;

- Undermine the ability of council and citizens to engage in a meaningful public debate - choices will be limited as developers respond to the public issues prior to Council making decisions;

- Increase the frequency and severity of negative impacts on existing users of groundwater resources by permitting additional unserviced development to exceed the safe yield capacity of the existing aquifers;

- Increase the number of lost opportunities to extend municipal water areas with known groundwater problems at the Developer’s cost thereby committing the municipality to future servicing retrofit assessments and obligations;

- Increase traffic on the trunk highway network as well as to the Arterial system, in areas which may not have the adequate capacity;

- Increase cost to major infrastructure and service delivery (eg road construction, transit operations, fire protection, policing, etc.) and a subsequent increase in the tax burden;

- Undermine/reduce the success of the long-term regional plan if growth occurs in the wrong location;

- Loss of open space and resource land, unnecessarily, to residential development;

- Failure to respond to public feedback to take steps now to manage (regionally) unplanned growth.

Which you may recognize as a list of all the same issues plaguing the city today, 20 years after this list was first written. In the intervening years the city has developed and implemented countless plans: Regional plans, strategic plans and municipal plans. Also in the intervening two decades, the city has done almost nothing tangible to address any of those issues in any meaningful way. But hey, at least we’re getting yet another staff report about it.

In 2003, regional settlement manager Austin French and regional environment manager Peter Duncan wrote, “there will be significant negative impacts on future capital budgets if interim growth management regulations are not implemented and accelerated un-serviced development occurs.” That’s probably why, while preparing for 2023’s budget in 2022, budget and reserves manager Tyler Higgins and director of accounting and financial reporting Dave Harley wrote: “Municipal assets support the services directed by Regional Council. Condition assessments and improved planning have revealed that the municipality is not investing enough in renewal to maintain its assets. If willingness to pay for services does not match the cost to provide services and care for the related assets, service reliability will continue to decline as assets are taken out of service for safety reasons. Rapid population growth and demands for additional services are adding pressure to this imbalance.

“The portion of the capital budget funded directly from municipal revenues, Capital from Operating, is not keeping pace with needs … The proposed capital plan for 2023/24 has been reduced in response to this short.”

And the specific fire risks to Indigo Shores were first identified in 2003, when staff were concerned there wouldn’t be enough water. In 2017, an Armco engineer wrote to the city about Indigo Shores, arguing that Armco should be allowed to continue its unsustainable development. The engineer, Ryan A. Barkhouse, wrote: “An extensive water study was completed prior to concept approval. The quantity and quality have been proven as sufficient for the approved development.” And besides, the lack of groundwater didn’t apply to Indigo Shores “as there are no abutting lands that can be developed for residential uses. HWY 101 is to the North, McCabe Lake to the South, Margeson Drive to the East and the old landfill to the West.” In 2018, Halifax Fire told city council what water there was couldn't be used in an emergency, saying Indigo Shores was “built without appropriate fire safety specifications, such as inadequate water sources to fight fires.”

In 2003, staff were concerned that there wouldn’t be enough capacity for all the car traffic in the subdivision. “Does not apply,” wrote Barkhouse in 2017. “Since the original implementation in the 2006 RMPS [Regional Municipal Planning Strategy], the interchange off Hwy 101 to Margeson Drive has been constructed, and there is adequate capacity on the road network for the subdivision.” That’s why Indigo Shores only had one point of egress in a deadly emergency.

Staff were also concerned in 2003 about the increased “cost to major infrastructure and service delivery (eg road construction, transit operations, fire protection, policing, etc.) and a subsequent increase in the tax burden.” Again, Barkhouse had the answers in 2017: “A Park and Ride facility is planned on Margeson Drive, which will be convenient for the residents of Indigo Shores. No further transit infrastructure is likely to be required.” And as for fire? “There is interest in putting a dry hydrant on Drain Lake to increase fire protection in the area. With the growth control in place we will not be able to do this until approximately 2022 or beyond.” As an aside, dry hydrants are usually more expensive for a city to maintain than wet hydrants.

Then on Dec. 4, 2018, council made the political decision to abandon the secondary planning strategies that were incomplete after 14 years and switch to a more complete regional plan review for Middle Sackville. Councillor Lisa Blackburn said at the time she was “very proud” to be tabling this regional plan review. Councillor Shawn Cleary was optimistic about the increased transit in the area, and the sustainability of the planned development. “Given the sort of planned and unplanned mistakes that have been made in this area—it’s really crappy car dependant sprawl, sorry—but I was struck by the words ‘master planning,’” Cleary said at the time. He ended by saying he hopes “that our planning staff can fix mistakes of decades past.”

So far, staff's 2003 concerns about Indigo Shores, the issues with decades of bad development patterns and the mistakes Cleary mentioned remain largely unaddressed.

Many communities in the HRM continue to suffer from the same “mistakes of decades past,” making them extremely vulnerable in times of emergency.

While this all seems terrifying—and it is—there is some good news. In the press briefings during the fires, we learned that the people managing our emergencies are making decisions based on Halifax’s very real weakness. Unlike our politicians, they don’t pretend things are better than they are. They are professionals who understand the dangers we are facing, even if idiots burning leaves with propane torches do not. And this is the information being considered when they make decisions like banning us from bike rides on well-manicured trails that are far from the fires.

In the future, it is critical that we all follow the instructions given to us by the emergency management team. They are making rules based on the vulnerabilities of our city.

Hopefully you, the people of this city, are now starting to fully understand the scope of the danger created by the “mistakes of decades past.” The city has had countless plans and planning strategies since 2003 to address the issues identified 20 years ago. But so far, every single one of them has failed.

There are likely 17 elected officials and more than a few municipal bureaucrats who will take issue with the characterization of their governance of the city as a failure. Mainly because the governmental response has been the “correct” one. The city has identified a risk presented by the lack of emergency exits from badly developed subdivisions. The city has also identified that these exits need to be built because intense forest fires in rural parts of the HRM are going to be common in the future. And since this is an emergency, the city will likely get these exits built fast. But fast, for this city, means it will be a few years.

The Coast is labelling this municipal effort a failure because, for all the reasons this article has laid out, there will probably be another fire season next year that will probably be as bad as this year's. Probability also says that these fires are most likely to be in the rural areas of the HRM in communities developed with only one egress. Essentially, the inflexibility of our municipal government is forcing us to play a municipal planning priorities lottery—we will have to wait and hope next year’s fires don’t happen, or that they only burn in communities that now have two exits. Otherwise, we have to pray we are as lucky next time as we were in Tantallon.

Hopefully, these fires taught you that your life is being put in danger by our politicians. Because it is. Our politicians’ desire to maintain the status quo is a firm recommitment and doubling down on the “mistakes of decades past.” And every time our politicians double down on the status quo, it increases the effects of the climate emergency. It increases the odds that municipal governments can’t put emergency exits in deathtrap subdivisions in time. Politicians doubling down on the status quo means politicians are doubling down on making the climate emergency worse. Doubling down is our politicians pulling the goalie when the team is shorthanded to get an extra skater on the ice. It’s dumb. It’s why we are losing a winnable fight against climate change.

We need to start fighting for our Hollywood ending because, right now, we don’t have one. If climate change were a traditional three-act movie, we would be in the middle of act two: the point of no return. We have undeniable evidence that we humans are on track to wipe ourselves off the face of the planet.

The third act of Hollywood movies starts with something called “the major setback.” And with the country being on fire in what is the worst fire season on record, that’s more or less where we are right now.

But if we want to get to the happy ending of our movie and celebrate with a problematic victory montage, we need to start fighting for it right now. Because, unlike the movies, there will be no heroic scene where a reluctant hero steps up onto the back of a pick-up truck, galvanizing us to fight.