At Tuesday’s council meeting, the city’s elected officials learned that one of the city’s departments is slowly but surely suffocating Halifax’s future. But before that happened, there was a piece of good news: The Halifax Common Master Plan came back to council and got approval.

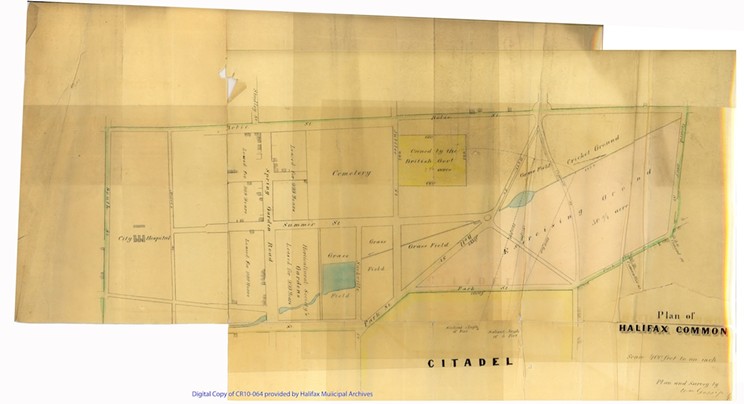

It was in 1763 that then-king of Canada George III showed how easy it is to be generous with someone else’s stuff, when he gifted a piece of Indigenous land to British settlers and proclaimed it “to and for the use of the inhabitants of the Town of Halifax as Commons forever.” This common space has undergone a lot of changes since then, but even as the city developed it around it, the military requirement to have clear lines of fire from Citadel Hill meant the former swampland emained relatively clear of development, although human encroachment around the edges has decreased the size of the Common in the past 261 years.

Defence of Halifax aside, the Common has been used by the people of Halifax for recreation for centuries. And as human existence is cyclical, all that is old is new again. In 1859, the Halifax Common has plans for a cricket pitch; in 2024 the HRM does again. In the 1940s it had a pool, and now it does again. It used to have more baseball fields, but we took one out for The Oval and only briefly looked back.

The Wanderers Grounds was created in 1869 when the city signed a lease with the Wanderer’s Amateur Athletic Club in 1886, which is when the part of the south Common we now know as the Wanderers Grounds was first created. Initially the grounds were used for cricket, rugby and lawn bowling, although by the end of World War II not much of the sporting, or any of the pre-war organizations that used the Common, remained.

In the intervening years since 1945, the Navy’s former dry canteen and stables were converted to the Lancers stables. Horse racing was replaced with a skate park, an unused field now has a temporary stadium and a professional sports team. The city decided it was time to herd these cats and come up with an overarching plan for the Common.

The early feedback, according to the staff report, is that everyone who uses the Common for recreation—the skateboarders, horse riders, and all the throwers, kickers and picklers of balls— wants to see improvements to the Common. The only people who are against improvements are part of the group Friends of the Halifax Common, also known as the Frenemies of the Common. At Tuesday’s meeting, city councillors sided with the recreation-minded andapproved the master plan, so detailed planning for things like a potential permanent Wanderers Stadium should come within a year.

Things that passed

The motion councillor David Hendsbee got deferred last meeting came back this meeting, and had to re-do first reading. So this will come back again, again, at a future meeting for second reading (again) after a public consultation. As a reminder, this is a motion to pave less than 5km of road, and this paving will cost more than $840,000. The people who live on the roads being paved will cover 33% of that cost, we’re picking up the leftover 66% of the tab.

That 30-storey mixed-used building planned for Robie and Spring Garden that the Friends of the Halifax Common don’t like came back for a public hearing. As predicted, that public hearing was pretty well-attended. This development was approved.

The Dartmouth Heritage Museum Society will have their funding boosted by the HRM. The Evergreen and Quaker Houses, along with a bunch of artifacts from the former Dartmouth Heritage Museum, have been under the HRM’s control since amalgamation in the ‘90s, but the HRM has only really started ramping up the preservation of Dartmouth’s history in 2019. The five-year agreement with the Dartmouth Heritage Society will be renewed and further bolstered to $200,000.

As mentioned above, the Halifax Common Master Plan came back, and everyone loves it except Friends of the Halifax Common, who don’t like the stadium. People expressed support for the skate park, expanding the Lancers grounds, adding pickleball courts and generally making everything better. The city wants to make North Park Street a “recreation link” with a broad pedestrian promenade eventually extending all the way to Point Pleasant Park. This plan doesn’t say yes or no to a stadium, but does lay out criteria for any stadium that might get built. All in all this plan sounds wonderful. This will come back in about a year with a functional plan for a Wanderers block (i.e. Wanderers stadium, Lancers expansion, etc).

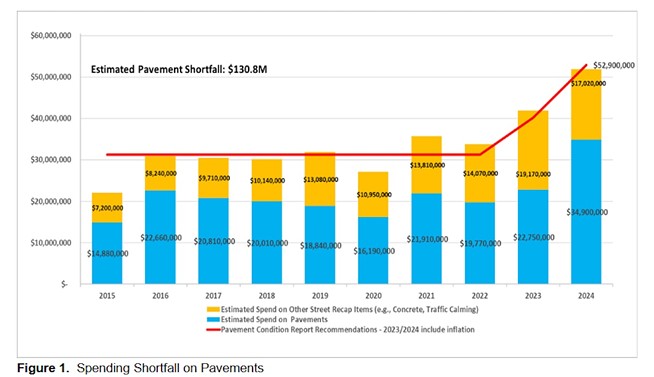

The street navigator program got multi-year funding because governmental inaction on the housing crisis still exists.

And after so much attention on Halifax’s future, the meeting turned to past mistakes that threaten everything we want to become. Simply stated, the road network is bleeding municipal coffers dry at an alarming rate. Staff are proposing to lower the standards of what the city considers acceptable pavement quality, so the roads won’t need as much paving in future years. Two years ago, the city’s Department of Public Works told council that maintaining the HRM’s roads to a “Good” standard (67% or a D in letter grades) was possible with more “investment” in HRM’s roads; staff endorse this course of action because maintaining the HRM’s unsustainable transportation infrastructure is a “core function” of Public Works. But two years later, since unsustainable is a defined word with a real meaning, that initial plan has been predictably borked by the aforementioned unsustainably. This year the city was predicting a $130.8 million shortfall in our road network alone to achieve that Good standard. In order to avoid spending this $130 million, staff told council that the city needs to think more like a horny sailor at 2:01am when the lights come up, and lower their standards (paraphrased). Council agreed, and now the city will let roads get to a D- grade of 60% before automotive infrastructure is considered for replacement. In other news, the city is planning to spend $2 million less this year on complete streets than it did last year, totalling $17 million. Meanwhile staff want to spend $12 million more, for a total of $34.9 million more on automotive infrastructure than HRM spent last year. In good news, the city dumped extra money, approximately $5 million, into sidewalks in the past few years and now 91% (A -) of the city’s sidewalks are in good condition, up from 66% (D) 10 years ago.

Council gave first reading to a bylaw that will make the city do a cost benefit analysis of paving before agreeing to pave gravel roads, among other things. Prior to 2000, developers could build subdivisions without paving them. Since this was approved it will (eventually) cost $15 million to pave them, of which the city will (eventually) pay $10 million.

The city is getting a new sidewalk policy due to “significant need, high cost and limited budget.” This is exciting as “experimentation with other, lower-cost ways to create safer places for people walking, especially on more local streets,” will become official policy. As it stands, even though the HRM has just shy of 4,000 km of transportation infrastructure for cars, the city was built without 800 km of transportation infrastructure (sidewalks, multi-use paths) for people. That’s 800 km of transportation deficit in the HRM, with 155 of those kms within the urban tax boundary. The city is planning “aggressive” sidewalk spending of approximately $97 million over 10 years to start correcting this deficit. For context, this is about three years worth of road spending. In this debate, councillor Patty Cuttle asked if the city would start using paths of desire as a blueprint for active transit infrastructure. HRMs active transit program manager, David MacIssac, told council that the city sees those paths as “quick wins,” and encouraged councillors to let his team know where they are. The city’s 311 info line is also able to take these suggestions and pass them on to staff. When addressing the city’s 800 km sidewalk deficit, Hendsbee wanted to know why we couldn’t count paved shoulders as sidewalks. Here’s why, councillor Hendsbee:

One reason why I think it’s important to continue to highlight the absurdity on our streets is that most people just don’t see it. Despite it being obvious to some, so many don't have real clarity because we have done such an incredible job of normalizing this imbalance. pic.twitter.com/xYgrsb6SRU

— Tom Flood (@tomflood1) August 11, 2023

But more on how the Department of Public Works is slowly but surely suffocating the life out of the HRM in the Notable Debates section below.

Thanks but no thanks: The city won’t take ownership of the Woodland Avenue Fence.

Because the province changed some legislation, the city has to issue fines for any short-term rental operator who does not submit a monthly report. Some people who made no money and owed no levy didn’t file reports, and now have to pay a fine. Councillor Sam Austin wants to know if the city can change the M-400 bylaw to forgive those fines. The city might be able to do something here, but it’s extremely limited due to the fact that this stems from provincial legislation. This will come back with a staff report with recommendations post haste.

Notable Debates

The Department of Public Works is causing the downfall of Halifax. Not in the form of a malicious overthrow of HRM’s municipal government, but instead a slow erosion of the HRM’s legitimacy fuelled by good intentions and bad assumptions. The three transportation motions council heard on Tuesday were in service of the budget debates which start this week and last until April 23 (or April 30, if required). And this budget season the city finds itself in a deep dark budget hole created by a development agenda that always put the automobile first.

The city is at the end of a generational Ponzi scheme, or as mayor Mike Savage told the Audit and Finance Committee last Tuesday: “For a long time people would come to a city—any city, not just Halifax—and said, ‘Look, we'll build here. We'll build the roads, we don't need libraries, we don't need transportation, we don't need rec centres.’ But the people that move there want those things, and I bet you if you went to every district of HRM you'd find somebody who says, ‘We pay a disproportionate share of taxes versus the services we get.’” This anecdotal feeling is backed up with evidence every time the city looks into it. For example, Halifax’s 2024 rural recreation strategy update explains how this is true for rural residents who pay taxes for recreation.

What this means for everyone is that the city doesn’t have enough infrastructure to meet the needs of the people who live in the HRM. This is something known as “infrastructure deficit.” The deficit isn’t easily quantified in the HRM, but we know that as of 2008 this national development pattern of roads and houses created about $60 billion of infrastructure deficit in Canada. This $60 billion deficit was expected to grow by $2 billion a year based on 2008 inflation projections, making the national infrastructure deficit now likely over $100 billion. How much of that infrastructure deficit is in Halifax specifically is extremely hard to quantify.

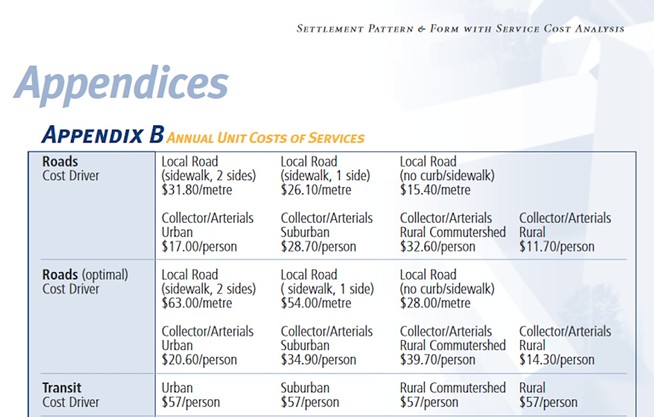

We also know that Halifax’s current infrastructure—the roads and bridges and other stuff we have already—is going to cost us a lot of money to replace, about $4.3 billion. It’s hard to say for sure how much our automotive infrastructure costs us, all we know for sure is that we knew it was going to cost us, cost us a lot, and we built it up anyways, massively subsidizing cars at every turn. In 2005, the city predicted the cost to attach each home to automotive infrastructure cost $63 per metre (this is about $100 per metre in today’s money). This report also highlights that what the HRM actually charged for roads in 2005 was $31.80 per metre, half the cost, meaning back in 2005 the HRM’s road subsidy was 50%. Today, paving a gravel road costs just shy of $400 per metre and the municipal subsidy for that has gone up to 66%.

These historic and continued subsidies for cars and car-dependent infrastructure are a result of a Department of Public Works and a city that just can’t think about transportation without prioritizing cars. For example, when director of public works Brad Anguish was explaining the lowered paving standards, he said that if our road network got too bad it would be extremely costly to replace our roads. But that’s only true if the city of Halifax is throwing out its strategic plans like the Integrated Mobility Plan, the Strategic Road Safety Framework or HalifACT.

To be fair to Anguish, replacing roads with roads one for one would be fiscally irresponsible, borderline impossible, because automotive infrastructure is so very expensive. But according to Anguish, who repeatedly tells council that maintaining the road network is a top priority, a “core function” even, also somehow never seems to recommend increasing user fees or taxes to cover the increasing cost of road maintenance, nor does the department recommend reducing automotive subsidies. In other words, even though maintaining roads is a “core function” of the department, they never suggest ways to decrease the fiscal burden of the infrastructure they oversee. On top of that, if roads do fall into a massive state of disrepair and need to be replaced, HalifACT, the IMP and Safe Streets Framework all say we should be replacing automotive infrastructure with more holistic, decarbonized, cheaper, sustainable transportation infrastructure.

Unlike automotive infrastructure that only costs the government (costs government a lot), holistic transportation infrastructure generates revenue for cities and provinces. According to David MacIssac, HRM active transportation program manager, an aggressive 10-year build-out of non-car infrastructure will cost $97 million. Since people weigh a lot less than cars, when the city builds non-car infrastructure, it lasts a long time. The city spent $5 million over the past few years on human transportation, and bumped sidewalk conditions from a D up to an A-.

Ignoring that the Department of Public Works’ car-centric planning is killing the planet and preventing Halifax from achieving its HalifACT goal of decarbonizing transportation; ignoring that the department’s car-centric planning is preventing Halifax from achieving IMP’s modal shift goals; and ignoring that the department’s car-centric planning ignores the safe streets framework which is literally killing people; the Department of Public Works’ car-centric decision making is also preventing itself from completing its “core function” of road maintenance. Even though our roads are heavily subsidized and that subsidy is both decreasing municipal revenues and increasing the maintenance burden, the DPW fights tooth and nail to keep cars on the road and prioritize drivers.

To be honest, if people followed municipal politics like they follow sports, there would be braying for blood. In sports it’s easy to recognize poor performance and poor leadership, because it shows up in the standings. In municipal politics those scoreboards are hidden behind titles like “attachment A” and “appendix C.” If people could read those scoreboards and standings like Wanderers fans could in the summer of 2022, there would be cries around the city for the director to be sacked.