Yesterday municipal budget season officially kicked off. In the coming weeks, you’ll be hearing a lot more from and about the city’s (about-to-retire) chief administrative officer, Jaques Dubé, and its (unofficial) captain of budget season, chief financial officer Jerry Blackwood, so here’s a bit of an explainer on how the budget process works. It might be a little boring but it’s critically important, so here we go.

Halifax Regional Municipality’s budget, like any budget, is about figuring out how much the city needs to spend and how much money it needs to bring in to cover those expenses. The HRM’s budget is broken down into fixed costs and discretionary costs. Fixed costs usually make up the bulk of the budget expenses.

Fixed costs are things the city knows it has to pay and exactly how much it will cost. City employee salaries, for example, are a fixed cost. There are also fixed costs that are contractually obligated, like the city’s agreement with the RCMP. The HRM knows it’s in a contract with the RCMP until 2032 and factors that into the budget.

The discretionary costs are things that change from budget to budget. For example, if the city wants to install a milkshake fountain at the Dartmouth Common next summer for the North American Indigenous Games, that money would come from the discretionary pool. If the city wants to turn the milkshake fountain into a permanent thing, it would turn into a fixed cost.

In preparation for budget season, the CFO and CAO add up all costs the city has and estimate the cost of things the city wants to do. They also figure out how much money the city is likely to pull in from various sources, mainly property taxes. They’ll try to predict how much more money the city will need based on population growth trends, as well as people’s ability to pay their taxes. There’s a lot of legal complexity, but the massively abridged version is that cities are expected to provide most of the government services we rely on without a way to pay for them—except with property tax revenue.

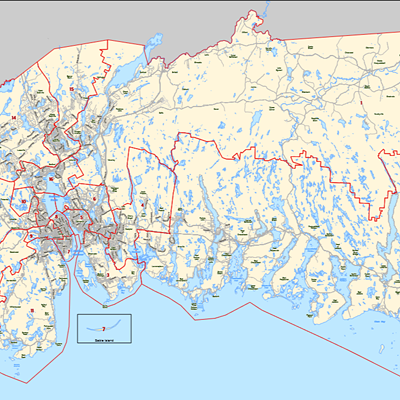

With all of that research done, the CFO and CAO (mostly the CFO) also figure out what they have to do with the property tax rate in order to fund everything. This year the projection is an 8% increase. Which averages out to an increase of approximately $173 for each residential property in the HRM (slightly higher in the city, slightly lower in rural areas). It's also worth noting that the suburbs lose cities a lot of money by design and this city they are also taxed like rural areas, but serviced like urban ones.

Nov. 22 marks the start of budget meetings. The first meeting is a bit of an exhibition game. It’s a strategy meeting to make sure the city’s bureaucracy and its elected officials agree, broadly speaking, on how the city’s money should be spent. Since the HRM is in the middle of a five-year strategic plan, there shouldn’t be many surprises at this stage.

The HRM is a place and a municipality, but it’s a corporation too, and the corporation is divided into “business units,” like Halifax Regional Police and Halifax Transit. Once the CFO and CAO do the math, they tell the city’s various business units what they’re going to recommend to council as a budget, and direct the business units to come up with a plan on how to spend their allocated money. Anything over their allocated money is called a “budget over.”

The business units then come to the municipal government’s budget committee—a group of city councillors—and explain how they’re proposing to spend the money based on the CFO’s plan. They’ll also include what they want to do above the money they’re given, and ask for money for it. If these extras are approved by the budget committee they’re put on something called the budget allocation list. These meetings are the bulk of budget season—its “regular-season games,” if you will.

Once council decides on what extra stuff is important to include in the budget, it has a final meeting (or series of meetings) where it deals with the budget allocation list. Council decides what to cut and what to keep, then tells Blackwood to figure out how to pay for it. These meetings are the “playoffs.”

Blackwood figures out how to pay for it, puts it all together in a final budget and council votes on it. If it passes this step, the budget is done. Until next year. Or, if COVID gets real bad again, maybe another budget will be recast in the summer. That’s what happened a few years ago.

The big financial problem the city has this year is that it’s broke.

Council’s focus in past years on reducing taxes means the services the city provides, like the library, are now very lean because the city has been steadily cutting them back. And reducing taxes leaves the city with less money to spend. Other levels of government have the option of running a deficit budget—going into debt—to “pay” for expenses. The HRM can’t. The HRM can borrow money, but it needs to ask the province for permission first after this fall’s sitting of the provincial legislature. The city legally has to have a balanced budget. It also legally has to do things like repair buildings. So the choice before council, really, is one of three things:

- Cut services

Since the services we get now are already incredibly lean, further cuts will be extremely noticeable unless services with limited value additions to society are cut, like the police. We likely would not notice a significant cut in police services. In fact, in New York when the police went on strike, crime went down with fewer police on the streets.

- Raise taxes

It means taxes don’t skyrocket later, and the city can do more stuff that we need, like build bike lanes.

- Don’t cut services, don’t raise taxes

This is the worst of the three options. No matter what, this means taxes will have to go up more than we might have expected this year, but it won’t happen until later years.

Practically speaking, what this means for you is the following: You can complain about potholes not being fixed, or you can complain about taxes going up. But you can’t do both.

Well, you can do both—but it’ll just let everyone know you didn’t read this article, and we’ll judge you.

Like this

And just one final note, the city is trying to move towards a different service-based taxation model. If implemented correctly, it will be a massive benefit to the city. But in that process, the financial jargon around "budget overs" is and will be changing. And in a few years, this explainer will also have to be fundamentally changed. But until then, sit back, stress out and rant at your friends about how the city spends your money.