In some cities, a cemetery plot is prime real estate. An overabundance of the living leaves little room for the dead, driving down the availability of cemetery space even as prices for plots go up. A grave in perennially-overpriced Vancouver can cost as much as $52,000.

But there’s a different kind of spectre haunting some of Halifax’s burial grounds. As congregations dwindle, church officials are looking to the municipality to adopt cemeteries that have been orphaned by church closures.

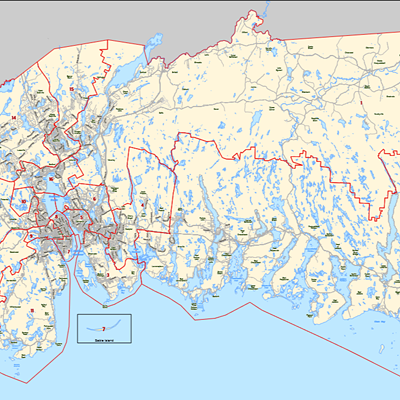

Five parishes on the eastern shore have petitioned HRM in the hopes that the city will assume responsibility for the cemeteries that will be left after the buildings themselves are sold or dismantled.

In September, Councillor David Hendsbee, whose district is home to the churches in question, brought forward the motion for the city to take over these cemeteries. A staff report on the issue is forthcoming.

The municipality might be the measure of last resort, Hendsbee said, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a moral obligation to step in.

Although the HRM doesn’t have a set policy on cemetery adoption, the city already looks after six burial grounds; two in Halifax and four in Dartmouth. Unsurprisingly, owning a cemetery isn’t exactly a license to print money.

The Camp Hill Cemetery, which the municipality took over from a private company in 1944, has a maintenance fund that generated a grand total of $6,658 in income in 2014-15. Cemetery maintenance for the same year, by contrast, cost the city around $256,000.

Currently, the municipality’s burial fees don’t even cover the $87,000 spent cutting the graveyards’ grass. And the situation could soon become bleaker. This past week council agreed to reexamine cemetery fees for burials after 4pm ($150) and on weekends ($500). That’s in addition to the standard municipal interment and lot fees, which can be thousands of dollars.

The after-hours fees theoretically go towards paying for overtime and maintaining the future upkeep of the cemetery, but as of right now they don’t even cover the total cost of the burials. Last year council asked city staff to look into eliminating the extra fees outright—a plan staff says will potentially lose $23,000 in annual revenue. Staffers instead suggested reducing the fees, which was met this past week with outrage from some councillors.

“We can’t plan when we die, nor can our loved ones,” said Stephen Adams, who called the after-hours fees “obscenely unfair.” Eventually council asked for another staff report on the matter.

Several councillors responded to David Hendsbee’s motion back in September with concerns that the costs of looking after more cemeteries could prove a dead weight on the municipality’s already limited finances. Waye Mason, councillor for Halifax Peninsula South, was one of them.

In a phone interview, Mason says that when cemeteries are started as for-profit enterprises, they shouldn’t then be looked after on the taxpayer’s dime. For the city to naively put itself in a position of responsibility could be a grave mistake, indeed.

“It’s a perfect microcosm of what government struggles with all the time,” Mason says. “Are you paying the true cost of the service, or if we let you do this thing now, is that a future liability for [the city]?”

As it’s probably safe to say a massive uptick in church membership is unlikely to come to the rescue, making the scale of this particular financial problem yet to be determined, Mason suggests the province should step in and help.

Securing the involvement of government is important, says Bob McArel, because even when a church can no longer care for its cemetery, it isn’t off the hook.

“Once a church gets involved in a cemetery, there’s no walking away from it unless they transfer ownership,” he says. “It’s just an obligation.”

These churches might not be able to afford to care for their cemeteries, but by any moral currency, they can’t afford not to.

McArel is a member of the United Church. He also has an appreciation for the regulatory side of things, having worked in labour relations pre-retirement. Sitting down at a table in the Alderney Ferry Terminal, he pulls out carefully-highlighted copies of the provincial legislation on cemeteries—the fruits of research that began four years ago when his own church was determining whether it was responsible for a nearby burying ground (it wasn’t). He doesn’t like what he sees.

“In the next 10, 15, 20 years, unless things really reverse, today’s problems are going to get bigger.”

Under provincial regulations, a cemetery operator can enter into an agreement with the city which makes the municipality responsible for cemetery maintenance, though there’s no obligation for the city to do so.

The act also allows the province to appoint a trustee to look into a cemetery’s finances. That’s something the city can’t do, says Mason, arguing it’s another reason why the province should take over.

What the regulations don’t state, though, is that the province is required to pay for cemetery maintenance, and there are no provincial programs in place for this purpose.

Ideally, this is the cemetery’s job. For-profit cemeteries are legislated to put a percentage of the proceeds from grave sales into a perpetual care trust fund, which then furnishes the cemetery with the necessary funds for upkeep until, you know, the end of time.

But churches occupy a murky no-man’s land as far as regulations go, and are actually exempt from these rules. Churches aren’t considered private businesses—which means that, somewhat infamously, they also don’t pay taxes—and aren’t required to set money aside for perpetual care. As a result, some burying grounds are flush with cash, while others don’t have a cent.

This is equally true for the five burying grounds in question. Two of the cemeteries have perpetual care trust funds of at least $10,000 each, says Reverend Joan Griffin. But the others have nothing.

Griffin is the Reverend responsible for the five cemeteries in peril—Clam Harbour, Lower Ship Harbour, St. James, Oyster Pond and Owl’s Head. She’s also responsible for the three active United churches in the Musquodoboit area, which she says was once home to 10 working churches.

Between the five cemeteries, Griffin says she conducted around 12 funerals in the past year. And there are people still living in these communities who hope to be buried in those cemeteries, she says, next to their family members, neighbours, friends.

So why can’t the United Church of Canada step up and assume responsibility for the upkeep of their own denominations? As it happens, these are lean times for churches everywhere, says Griffin, and the national administration doesn’t have the money to cover regional church costs.

It isn’t just the United Church. Different denominations are cozy out on the Eastern Shore, says Griffin. When the representatives from these once well-attended churches get together, they all say the same thing: “It’s changing times.”

Those changing times have left these cemeteries orphaned twice over; it’s unclear who’s supposed to look after them, and it’s even less clear who really wants to. Those most affected are currently underground, but that doesn’t mean the issue can be forgotten, especially as congregations around the province continue to shrink. A clear policy set down by various levels of government would at least tell future congregations where those resting in their cemeteries stand—er, lie.

In the meantime, Griffin asks that people think of the residents of these cemeteries not as members of a particular church, but as family members, friends and ancestors. Anticipating a rallying cry of “not my tax dollars,” Griffin has a bone to pick with those who’d dismiss cemeteries as economically unsustainable.

Who we are as a society is a function of how well we care for one another, she says—and this applies whether those we’re caring for are walking around on the earth or resting beneath it.

Moira Donovan is a freelance journalist in Halifax. She’s still working on being able to sit through an entire horror movie.