During the HRM’s final budget preseason meeting, on December 12, councillor Trish Purdy caught a lot of stick. Tuesday’s budget meeting was the Capital Updates and Advance Tenders meeting. The capital update is bleak: We need a lot of capital projects—arenas, libraries, fire stations and the like—but we have no money.

We have no money because suburban development and our automotive transportation monopoly have been slowly siphoning money out of our pockets and municipal coffers, and using it to entrench the power of massive multinational car conglomerates as a transportation monopoly. It also enriches oil companies, for which private car transportation is about 25% of their revenue. That money does not trickle back down. From the extremely high cost of automotive infrastructure maintenance, to subsidized-so-much-they’re-practically-socialist street parking spaces, the city is hemorrhaging money on transportation infrastructure.

Our transportation money issues are also exacerbated every year by the political problem known as the tragedy of the commons. Every year, councillors demand staff come back with low tax rates and an increased spending in mono-automotive infrastructure construction and maintenance. Even though switching to sustainable infrastructure, like using our roadways for buses and bikes in line with the city’s strategic priorities, is something council could direct staff to do at any time on any HRM road, they consistently choose not to. They don’t make changes because, even though environmentally and fiscally sustainable infrastructure is wildly popular after it’s implemented, *before* it is implemented it’s wildly unpopular. And every four years councillors have to win a popularity contest for their power.

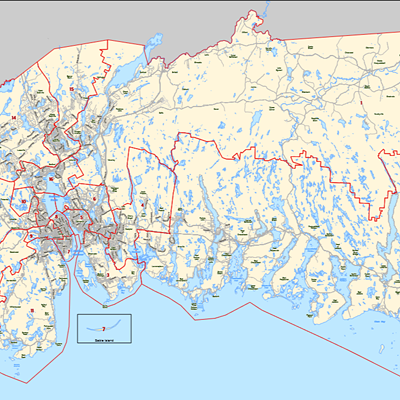

The city’s bureaucracy can, or at least should be able to, change quickly. Other places in the world, like Seville, can build a city full of bike infrastructure in four years. In Halifax we can’t seem to build a single bike lane in the same amount of time. That’s because the city’s bureaucracy is set up to plan, not set up to do. In order for far-flung parts of the HRM, like Cole Harbour, to get sustainable infrastructure, the city has so far required itself to do elaborate and repetitive planning exercises.

For example, first the city needed to get a report to see if the suburbs, like Cole Harbour, were, in fact, slowly bankrupting the city. In 2014 we found out they are. (This is also something the city learned in 2003.) Then, at the risk of addressing the problem too quickly, council started with a small correction to the suburban fiscal liability, the Centre Plan. This has been an eight-year, two-part planning process that saw Part A drop right before COVID, and Part B wrap up in late 2021. The end result of this planning has been to limit suburban sprawl, as growth has been encouraged in the Centre Plan area. With that planning completed, the city will now focus on coming up with a plan for the suburban and rural areas. Once *that* planning is finished—remember, it took eight years for the Centre Plan—then the city will be able to start doing functional transportation planning goals. Right now, the city is planning on starting the sustainable transportation planning for Cole Harbour in 2029, the year the earth is expected to heat up past our current climate targets. (Note to councillor Tony Mancini: Just in case you were curious, that’s why the adulations for Halifax’s climate plans are not rolling in from your constituents.) This is why history will not be kind to Halifax’s current councillors.

And to top it all off, on Wednesday, the day after the capital updates meeting, the Audit and Finance Standing Committee got a report from city staff, which is being sent to the province, about the fiscal risk of the HRM’s infrastructure. The Provincial Financial Indicators report is something the city has to do every year, and this report is from last year. In the report to the city, two finance staffers write that although this report says things are good, that’s because the information the province asks for is very surface-level, as it’s data gathered from all municipalities. Things may not be as rosy in the HRM specifically, especially if staff were to use HRM’s reporting standards. But even in this rosy-ish report, Halifax’s infrastructure risk—that is to say the difference between how much our infrastructure is worth vs. how much it costs us to maintain—is increasing and should move from moderate to high by next year, unless that has already happened earlier this year.

All of this context is why councillor Purdy’s fairly innocuous motion in a budget pre-season meeting threw a loose public-good wrench into the city’s bureaucratic machinations.

Essentially this advance tenders budget debate gives city staff the okay to start preparing tenders to go out the door as soon as the budget is approved early next year. The city relies heavily on private companies instead of public departments to build the city’s public goods, and those private companies need advance tenders as indications that the municipal money pot will be open again this summer. This way private companies can start staffing up for the summer, which in turn helps in getting more work done during the short construction season. It is important to note that these advance tenders serve more of an advisory/planning role and are not actually a commitment to spend money. That approval comes in later budget meetings.

Councillor Purdy, who wants lower taxes and is aware that cars start costing money as soon as they are purchased, asked if there was any way to decrease the vehicle fleet replacement budget, which is proposed to be over $24 million in the advance tenders document. She suggested that it could be reduced by half, and put forward a motion to try and get her fellow councillors’ support. A lot of other councillors, including Mancini and Becky Kent, blasted Purdy for her motion, going so far as to call it premature and irresponsible. They argued that citizens who call emergency services want fire and police to show up when they call 911. And if police and firefighters didn’t have their cars or trucks, then the city would be derelict in its responsibilities to care for citizens in an emergency.

Ignoring for a moment that people sleeping outside in the winter is also an emergency rife with government dereliction, this process highlights an area where the city could make (and really should have already made) a tangible improvement to functionality of the city’s bureaucracy.

Because there might be legitimate, practical ways the city could save money on fleet vehicles and still make sure fire trucks show up when we call 911. Other places in the world have cheaper, smaller fire trucks, are those an option? If the city is planning on a modal shift, is it possible to fit cheaper smaller emergency vehicles in wide bike lanes like they do in parts of Europe? This type of holistic, functional transportation planning and problem solving has so far been relegated to smaller, slower geographic functional plans. Which all rely on three or four layers of larger municipal planning documents. Each of those involves a planning process, which need to be completed sequentially, due in part to councillors keeping taxes low. But that in turn means they each take a few years to complete.

As for cop cars, while it’s true the police need to move around the city, it’s also true that walking or biking beat cops are better for the city’s public safety efforts than cops in patrol cars. Are there patrol cars being used in the Centre Plan area that could be replaced by ebikes, and could that save us some money on cars? This type of holistic planning for the future of policing is not something our Board of Police Commissioners seems interested in doing, instead preferring to defer to the current desires of the police.

Do new municipal crews need large trucks to do their work, or could they use cargo bikes like FedEx and at least one local carpenter? Could the city buy ebikes or etrikes and winter jackets instead of cars?

There are a lot of alternatives to fleet vehicles that should be considered if our municipal government genuinely believes this is a climate emergency. Instead, councillor Purdy’s motion was defeated and she told her peers she will come back after “doing her homework.” City staff left the capital budget planning meeting with no instructions to plan for or consider more fiscally and environmentally sustainable fleet vehicle options to save money. There needs to be evidence-based guardrails, but the city should be incubating and fostering new ideas that could help with the twin fiscal and climate emergencies facing the city of Halifax. Historically, and so far this budget season, it has not.

What this budget pre-season has taught us is that our municipal government is not flexible enough to adapt to the rapid changes required by the ongoing climate emergency and the future of our climate-changed world.

But Purdy’s motion, and things like the advance tenders plan to dump massive amounts of money into automotive infrastructure instead of environmentally and fiscally sustainable congestion-reducing transportation alternatives, suggests that this will be another wasted year in Halifax’s fight for its citizens' climate survival. Just in case some councillors care about the dereliction of the city’s response to its citizens when we call for help in an emergency.