In June, the residents of Wentworth Valley awoke to an unfamiliar—and unwelcome—noise. Tree-harvesting machinery had made its way up the western slopes of the valley and was chewing through the mixed Acadian forest atop the mountain.

By the time the media reported the story, the machines—working day and night—had already clearcut nearly 200 acres and left a gaping brown scar on the otherwise beautiful treed hilltop. The cut was across from Ski Wentworth, which each year attracts up to 80,000 outdoor enthusiasts.

There was

Asked about the clearcutting, minister of natural resources Margaret Miller told CBC there was nothing the government could do. It was private land.

Private land, yes, but this was land that the people of Nova Scotia had helped foreign corporations purchase. In 2010, the NDP government of Darrell Dexter loaned two American firms—the owners of the Northern Pulp mill in Pictou County—$75 million to purchase 475,000 acres of forested land in Nova Scotia from another American company, Neenah Paper. As part of the deal, the province immediately repurchased 55,000 acres of the same land from Northern Pulp for $16.5 million. Northern Pulp paid $172.63 per acre. Nova Scotia paid $300 per acre. The province was gifting the company $7 million. The $75-million loan doesn’t have to be paid back until 2040, but a Freedom of Information request failed to disclose on what terms.

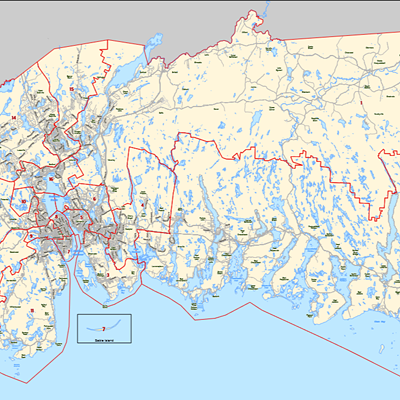

Large parcels of land in and around Wentworth were part of that deal. Surrounded by a 36,410-acre piece of property that Northern Pulp acquired was a smaller parcel of land on the eastern slopes that the province repurchased. It was supposed to have become a protected area—something the Ecology Action Centre has been requesting, in vain, for years.

The clearcutting from this past June was on a 6,184-acre piece of land that Nova Scotians had financed for Northern Pulp (or more specifically its sister company, Northern Timber). Both companies are subsidiaries of Northern Resources Nova Scotia Corp., which counts former Progressive Conservative premier John Hamm as its board chair. A year after the land deal, that whole family of businesses was bought by Paper Excellence Canada, a company that owns six pulp mills in Canada and is linked to the billionaire Widjaja family of Indonesia.

What was happening in Wentworth—the clearcutting of Acadian forest by a large foreign-owned pulp mill and a government bending over backwards to accommodate it—was nothing new in Nova Scotia. Nor was the public outcry. It had been going on for a very long time, ever since big pulp moved in.

Setting the pattern

In the late

A medium-sized mill had been operating in the province since the 1920s, when the Mersey Paper Company, founded by industrialist Izaak W. Killam, set up shop in Brooklyn on the south shore. Even back then, the industry seemed able to get what it wanted out of the provincial

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, large American pulp and paper interests had been acquiring—by purchasing or leasing—vast swaths of land in Nova Scotia. Unlike other provinces, where most property is publicly owned, only 29 percent of Nova Scotia is Crown land, leaving much of it wide open for large foreign investors.

In the late 1950s, in its efforts to lure Swedish company Stora Kopparberg to build a pulp and paper mill in Port Hawkesbury, Stanfield’s government handed the industrial giant a 50-year lease on 1.5 million acres of Crown land, with a rock-bottom stumpage rate of $1 a cord—the same accorded the Mersey mill 30 years earlier.

But another even larger company was eyeing Nova Scotia. Scott Paper of Philadelphia had already acquired more than a million acres and was looking at building a new mill in the province. In 1963, Stanfield commissioned a report by two forestry experts, R.M. Bulmer and Lloyd Hawboldt, to determine whether the province’s woodlands could sustain a third, far larger pulp mill. They

Stanfield was having none of it. In their 2000 book, Against the grain: foresters and politics in Nova Scotia, L. Anders Sandberg and Peter Clancy document how deputy premier and minister of finance G.I. Smith summoned Bulmer and Hawboldt to a meeting that dragged on for a week. Smith refused to take no for an answer. The new pulp mill, which would consume more wood than all others in the province combined, would be built in Pictou County. Science and scientific advice about sustainable management of forest resources be damned. It was a pattern that would persist.

Clearcut, spray, repeat

In its efforts to entice Scott Paper to the province, the government made such a generous offer it could hardly be refused—with gifts of free infrastructure, extremely cheap water, tax holidays, the use of Boat Harbour for effluent and the responsibility for treating it, too. The Scott Maritimes Act, passed in 1965, also gave the company a 50-year lease on 230,000 acres of Crown land in Halifax County, on which stood some of the finest timber in the province.

But Scott wasn’t interested in selectively harvesting high-value timber. Its policy was to clearcut, replant with preferred pulpwood species (such as spruce) and spray with herbicides to kill off

It’s no coincidence that the Small Tree Act was repealed the same year Scott came to the province. The legislation had been enacted in 1946 after forest workers and the public pressured the government to do something about the “high-grading” of forests on private land—cutting the best and leaving the rest, reducing the quality of future forests. New legislation brought in to replace the Small Tree Act was never really implemented, and eventually repealed in 1986. Between 1951 and 1983, sawlog harvesting dropped 60 percent and cutting for pulpwood increased by 500 percent.Biodiverse Acadian forests—a mix of high-value trees that also provide habitat for wildlife and pollinators, protected watersheds and stored carbon—were being transformed into pulp plantations.

tweet this

Woodlot owners formed an association and tried to get better prices for the wood that came

Over the years, waves of protests over the clearcutting and spraying garnered a fair amount of media and public support, but what renowned wildlife biologist Bob Bancroft calls the “race to the bottom” continued. The only forestry regulations were

In the words of one forester, “We are managing our forests to be a landscape of clumps and buffers.”

Tom Miller, a former woodlot owner of the year and passionate advocate for better management of the Acadian forests in his role as chair of the Friends of Redtail Society, says that if you want to picture what remains of healthy forests in Nova Scotia, imagine the front page of a broadsheet newspaper: “Where the periods are is where you’ll find the good forests.”

According to extensive research done by Genuine Progress Index Atlantic, in 1958, before the big pulp mills in Pictou and Port Hawkesbury went into operation, forests older than 80 years covered about a quarter of Nova Scotia’s forested land. Forests more than a century old accounted for eight percent. Four decades later, years during which pulpwood became the biggest driving force and

Revolving doors

There have been times when it looked as if things were about to change for the better. In the spring of 2008, for instance, journalist and author Linda Pannozzo remembers the excitement was “palpable” at public consultations to develop a new natural resource strategy for the province. Started by the outgoing Progressive Conservative government, the process continued under the new NDP government and culminated, in 2011, with the publication of The Path We Share: A Natural Resources Strategy for Nova Scotia 2011–2020. There were two major changes for forestry—clearcutting was to account for no more than half of all tree harvesting and there would be no more public funding for herbicide spraying.

Around this time, however, the NDP government was feeling immense pressure to support the flagging pulp industry. Between 2009 and 2013, it gave Northern Pulp $111.7 million in loans and grants. It pumped $50 million into the Bowater-Mersey mill on the South Shore (owned then by Resolute Forest Products), and eventually another $118.4 million to purchase the mill outright, assuming its pensions and liabilities. To save the Port Hawkesbury plant, the province spent $156

Then the government spent another $111.4 million to purchase 550,000 acres of former Bowater lands in southwest Nova Scotia, a move that the public endorsed on the understanding that there would be public consultation on how best to manage and use these lands for the public good.

Or not.

While 37,066 acres of the recently acquired land

Meanwhile, the forest industry turned increasingly to other low-value products—chips for export and biomass to create energy. In 2013, Nova Scotia Power opened a large biomass burner in Port Hawkesbury that ran 24-hours a day to power the nearby paper mill. But any idea that the biomass would be limited to “waste” from the forest—sawdust and bark—was a misnomer. Forests, which store carbon and need many decades to grow, were being cleared for burning as “green” energy. A petition started by biologist Helga Guderley to have the biomass plant stop burning round the clock garnered thousands ofBetween 1951 and 1983, sawlog harvesting dropped 60 percent and cutting for pulpwood increased by 500 percent.

tweet this

Then, in 2014, a former Bowater woodlands manager and a former senior forester with Nova Scotia Power were brought into the Department of Natural Resources as director of the renewables branch and deputy minister, respectively. They joined another former Bowater employee now working in DNR as director of forestry. As Pannozzo writes in the Halifax Examiner, “If nothing else, hiring the ‘company men’ certainly sent a clear message: The industrial forestry model was being re-entrenched as the modus operandi.”

The same year, CBC reported that premier Stephen McNeil had brought another person with ties to pulp into his government. Bernie Miller, who had been Northern Pulp’s lawyer in charge of environmental compliance for years and a registered lobbyist for Northern Pulp from 2009 until 2014, was named the Liberal government’s deputy minister of priorities and planning.

Given its hiring practices, perhaps it’s no surprise that McNeil’s government has been backtracking on policy changes unpopular with industrial forestry interests. In August 2016, minister Hines announced the modest target of 50 percent for clearcutting in the province would be dropped. “Times have changed,” Hines said. This, despite criticism from the auditor general about the province’s failure to protect species at risk and their habitats, which have been endangered by forestry practices.

During the election campaign in the spring of this year, when the Ecology Action Centre and others made clearcutting and forestry practices an issue, McNeil promised an independent forestry review. A few months after winning a slim majority, the premier appointed University of King’s College president and legal scholar William Lahey to undertake that review and report back no later than February 28 of next year.

Putting the value back in forests

Industry voices will likely have Lahey’s ear, but he would also do well to listen closely to members of the Healthy Forest Coalition and others who understand the importance of diverse, healthy forests.

One of those is Dale Prest. Son of former Nova Scotia Woodlot Owners and Operators Association president Wade Prest, Dale is an ecosystems services specialist with Community Forests International. He sees a need to diversify our forests and the products they can supply. A healthy Acadian forest, Prest says, can be managed to produce high-value and high-quality trees that help woodlot owners thrive and strengthen rural economies. And in the face of the climate crisis, a diverse Acadian forest is invaluable; it can store three times as much carbon as the monoculture softwood plantations so favoured by the pulp industry.

There’s twice as much carbon stored in the first metre of soil under a forest as there is in all the vegetation above ground. Clearcutting speeds up the release of that soil carbon, contributing to climate change. Eventually, after enough clearcutting, the soil becomes so poor that trees will hardly be able to grow back. Prest says he’s already observing this worst-case scenario in the Maritimes.

There are 30,000 woodlot owners in Nova Scotia. Most of them are small-scale, with few resources and no power to challenge the rock-bottom prices paid for wood by the few big mills that control the market. In Prest’s view, it’s one reason why rural poverty is so extreme in Atlantic Canada.

“We’ve pursued a model of forest resource development that returns money to the owners of capital, that is invested in machines and in the manufacturing of machines and the financing of machines, not to rural communities,” he says. “It’s a real opportunity lost.”

But that opportunity can be found again if government heeds the advice of the many forestry experts in the Healthy Forest Coalition and puts an end to the clearcutting, spraying and over-harvesting of our forests, giving them a chance to regain their diversity—and their real value.

Pottersfield Press.