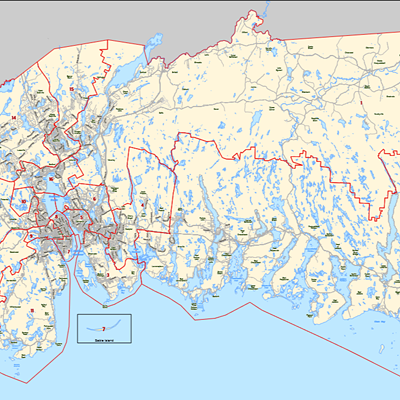

Halifax police are still waiting for an independent analysis of its street check data before deciding what, if any, action to take on the controversial practice.

In the meantime, more and more records keep getting added to the pile.

A January CBC investigation

“We need to do more research,” Christine Hansen, director of the NSHRC, recently told HRM’s Board of Police Commissioners. “We need to have an expert look at that, and then we’re gonna come back to the table and talk about what’s next, and what’s next depends on what we find.”

There are two types of files produced by an HRP officer from a street check: Instance and entity records.

Instance records have about 15-20 fields to enter information, says HRP research coordinator Chris Giacomantonio. Those fields include X/Y coordinates, street address, division, the officer involved, notes and the reason for the check. The check could be made for a person, or even for an object or place.

“So, if someone found a needle on the sidewalk where someone might not have expected intravenous drug use to happen, they might enter that as a street check as well,” Giacomantonio says.

An entity record is created if the check involves a person, and has a limitless set of fields for everything from birthdate to ethnicity, height and weight, eye colour and body modifications.

“A lot of those fields are populated through prior contact with the criminal justice system,” says Giacomantonio. “By and large, the street checks that Halifax Regional Police conduct are involving people who have past criminal history or past involvement with the justice system in some other way.”

All of this collected information is stored in Versadex, the database housing system that HRP uses to store criminal records and other information. Versadex is connected to a Police Information Portal which connects “90 percent of all police systems,” says HRP communications advisor Cindy Bayers. Any police department connected to PIP has access to all the Versadex records—including street check information—housed in HRP’s system.

Data sharing amongst law enforcement agencies—especially of non-criminal personal information—has been condemned by privacy and civil rights advocates elsewhere. In Ontario, local and provincial police routinely share “carding” information with RCMP and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

Halifax’s street checking policy looks a lot different than Toronto’s version of carding, says HRP. Officers aren’t just asking for IDs. Any interaction with police, whether it be in person or observed from afar, produces a record.

But if we’re going to compare ourselves against the standards of carding practices as a scale of judgement, there are other things to consider. As of January 1, Ontario has banned police from

Haligonians aren’t given the same courtesy of knowing when they’re being street checked, as an HRP street check can involve just a visual sighting of a person or object.

The Board of Police Commissioners, meanwhile, doesn’t yet have any policy in place on street checking practices. Until the NSHRC finishes its analysis and the board updates its internal policies, it appears the surveillance practice will continue in full force.

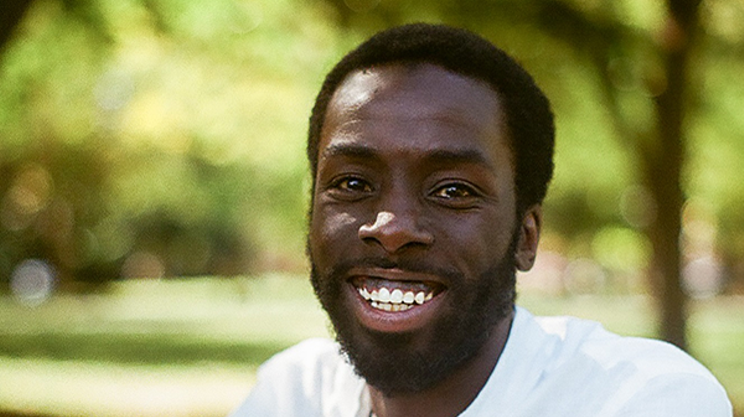

Marcus James was in attendance at a panel discussion on street checks that took place back in March and spoke about his own experiences being stopped three times by police while closing up the Halifax North Memorial Library. Continuing the practice means police are ignoring the pain felt by the Black community, he says.

“How many people need to come forward and share their pain, their experiences, before [HRP] is willing to sit down and look at bringing that to an end?”

Racial self-policing is the psychological result of being 1984’d by the police. The fear of the unwarranted attention given to specific people based on race causes them to learn behaviour in the hopes of diminishing the extra heat on their back. As Toronto journalist Desmond Cole writes in his award-winning article, “The Skin I’m In,” discriminatory surveillance causes people to feel like prisoners in their own city.

“Once you’re accused enough times, you begin to assume your own guilt, to stand in for your oppressor,” writes Cole.

James says he’s uninterested in sharing his own stories anymore until the police and the municipality step up.

“I just feel that until some real peaceful conversations, where we’re all at the table and looking at solutions on how we can move forward...for me, it’s really too painful.”