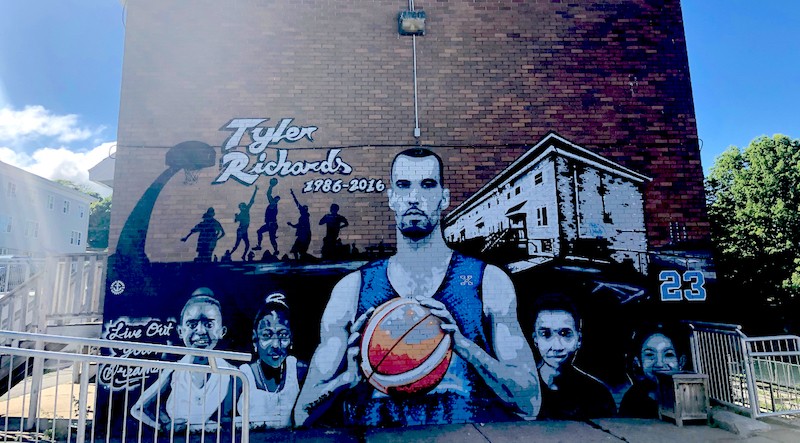

In the mural painted in his honour, Tyler Richards looks out over his community with a pensive, protective glare, a basketball clenched between his palms. He can see the Steps—the childhood meeting place where he and his friends would congregate and play, a place Mulgrave Park kids before Richards' generation and after have used as a hub, sitting on rust-marred concrete or swinging their tiny bodies around a green metal stair rail.

From the mural, he can see his mom's back door and the houses of his lifelong friends. And he can look up over the grassy hill to the basketball court off Richmond Street.

Richards' sleeveless St. Francis Xavier jersey radiates baby blue. His basketball glows. The smiles of the children on their feet beside him beam light—one of them his daughter, Niara, another, Ta'nyrah, who was like a daughter to him.

Niara's name is tattooed in a straight-letter tag on Richards' right forearm. The name of his other family is tagged on the wall behind him: the Wild 4.

This scene is Halifax, no mistaking it, as the iconic Tufts Cove smokestacks poke up behind Richards, fuzzy in the background. But the foreground—the centre—is Mulgrave Park. And in MGP, Richards is—was, will be—larger than life.

Except Richards isn't there anymore.

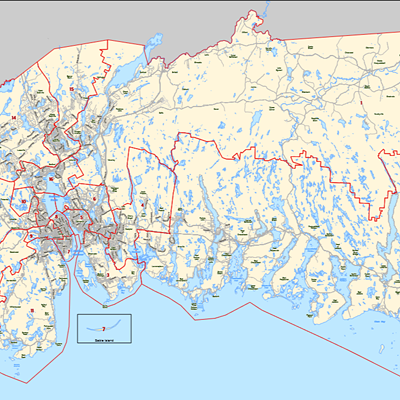

The white vinyl-clad one-and-a-half-storey house, where the 29-year-old was found dead from gunshot wounds April 17, is in Halifax's west end. Richards was the city's fifth homicide of 2016; as the year closes, we've racked up an ignominious 12 dead. It has been a year of violence in Halifax, undeniably. Over the past decade, only 2011 saw more murders, with 17.

You have heard the names of 2016's victims.

Blaine Clothier, whose friend has been charged with second-degree murder in his stabbing death. Joseph Cameron, shot to death, allegedly by a Dartmouth teen who will stand trial for first-degree murder. Frank John Lampe's son has been arrested for second-degree murder in his death in Clayton Park. The boyfriend of yoga teacher Kristin Johnston was charged with her second-degree murder in Purcells Cove. Tylor McInnis's body was found in the trunk of a car in St. Thomas Baptist Church cemetery. Four have been arrested in his death—three with first-degree murder, one with accessory after the fact. Shakur Jefferies was shot. An acquaintance has been charged with second-degree murder in his death.

Naricho Clayton was shot two days after Richards. Daverico Downey was shot less than a week after. Rickey Walker was found shot behind my old elementary school after calling 911 himself on August 31. Terrance Patrick Izzard was shot outside his Halifax home in November. Tyler Keizer was gunned down last month, too.

And Tyler Richards.

After police took down the caution tape and the news cameras left, the Cook Avenue house lay dormant, its raised bed garden sprouting weeds, the grass bolting. A phone book bleached in its delivery bag on the front porch well into May.

Neighbours reported hearing nothing out of the ordinary the night Richards died. But no Haligonian missed these shots.

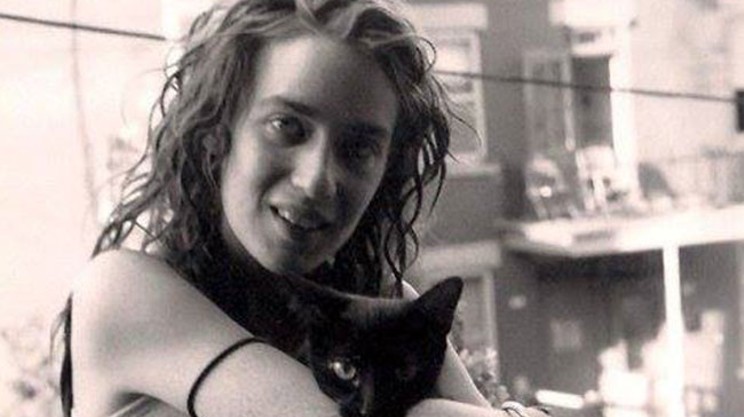

Richards was big in this city—a volunteer and community supporter. A four-time Atlantic University Sport all-star at St. Francis Xavier. A two-season combo guard with the Halifax Rainmen. For that, the media and the city gave more pause than the norm for homicide victims.

As April slowly warmed, MGP mourned. There were t-shirts and posters. Richards' friends, coaches and former teammates raised money for his mural tribute and a family education fund.

But outside MGP and Halifax's basketball community, the details of Richards' prior arrests invaded news reports and Halifax adopted its comment-section go-to: Thug gone, good riddance.

So, which is it, Halifax? Which is it?

• • •

If you ever need someone to sneak into Mulgrave Park on a clandestine mission, do not recruit Michael Williams.

Boys on the basketball court jab "Hey" mid-play. Teens nod. School kids warble "Hi, Mikie!" Williams' mom, Elaine, a longtime, big-time MGP volunteer, sings out from her porch, "Hi, my baby!"

Back at them all: The 32-year-old's upbeat "Hell-oh!"

Off Jarvis Lane, at the Steps, Williams becomes silent.

He doesn't live in MGP anymore. But when Richards died, the Steps was where Williams came, instinctively. And not only him. A memorial of grocery store flowers bloomed. Notes, photos and hand-drawn condolences. It made sense to paint the mural—where Richards surveys his community and his basketball shines—here, too.

Before Richards was a broad-shouldered 6'2" point and shooting guard, he was a skinny shirtless kid with an annoying laugh who hung out at the Steps. Williams knew Richards for two decades. Longer. So long, he doesn't even know. Early on, the two cut the bottom from a plastic milk crate and strung it on a clothesline on the wall at the Steps. "I was the one who sucked at basketball," Williams says, "but I was playing."

Today, Williams is an educational program assistant at Dartmouth High. He crosses the bridge five afternoons a week to supervise night hoops at Gottingen Street's George Dixon Centre or the Needham Community Centre, just up the hill from MGP.

In the stuffy Needham gym, Williams cracks open the metal doors for some air. Twenty-odd kids, mostly boys, from eight-year-olds to high schoolers, bounce basketballs in a cyclone. A little one is knocked to his bum. Williams jogs over to check as others help the boy up. The Wild 4—Richards, Williams, and their friends Christian "T-Bear" Upshaw and Andre Upshaw—were night hoops die-hards. Most nights as kids 20 years ago, the Wild 4 walked up past Jarvis Lane and along the fence to Needham, laughing along the way.

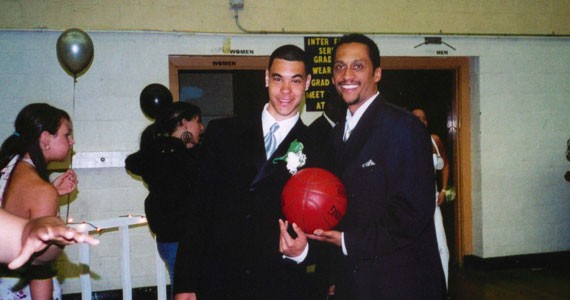

Richards was a joker, Williams says. Everyone says it. He scrolls through his phone to find a photo of a photo—Richards at his Grade 12 prom. Dark tuxedo trousers, light grey vest, shiny grey tie. St. Pat's graduates had a tradition: a small parade at prom where they would walk two-by-two with their dates. A little photo-op for parents. Richards marched with a basketball. Call her Spalding.

Richards was also plenty serious when he needed to be. His plan was always university. He was a youth program leader, pulled into it by his older brother, Tyrone. He volunteered at Needham Centre barbecues, at the annual Easter egg hunt in MGP.

Richards' strength was bringing people together, Williams says. As the memorial at the Steps grew, people came from the north end, the south end, Uniacke Square and MGP, Dartmouth, North Preston, East Preston, Spryfield, all over. "He bridged the gap between communities."

Unless you knew him, Williams says, "it's something you don't know. People are thinking 'Oh, he's this person.' But he was so much more."

• • •

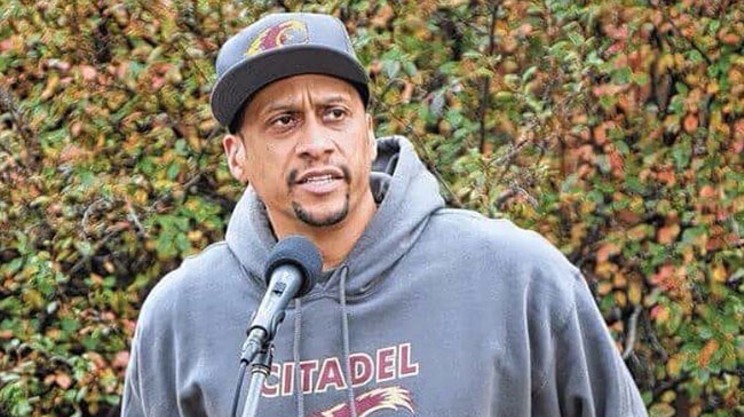

Robert Wright slides on a rolling chair from one side of his office to the other. Energy peels off him. I need to know a little about him, he says, before we get going.

"My mother had six children by five different fathers. So, despite having so many men in her life, she raised her children alone." First in north end Halifax, later on Greystone Drive in Spryfield.

Only two of the six kids graduated high school. A sister was murdered in Wright's Grade 12 year. A brother did time for robbery. Only Wright went to university—finishing a Masters. He's been a child protection worker and a race relations officer. He completed his clinical social work training with mentally disordered offenders in protective custody and on death row at Washington State Penitentiary. He was the head of Nova Scotia's Child and Youth Strategy. These days, he runs a small private social work practice and is poking away at some post-grad work at Dalhousie University.

"Psychologists are looking at what's going on here," he says, touching his head. "Social workers"—he swoops his arms wide—"are here, looking at the systems impacting individuals."

Wright didn't know Richards, but he knew of him.

The African Nova Scotian perspective—a frame of reference Wright shares by way of his own backstory—"is an important one in understanding the context of the violence that's going on and understanding Tyler's situation and others like his."

• • •

Time for a history lesson.

In the '70s and '80s, Nova Scotia shaved off a large chunk of its resource- and labour-based economy. Before that time, lack of education didn't present a significant barrier to earning a living.

"Half a generation ago," Wright says, "if you were in junior high, and you kept coming home, getting into trouble, your father would slap you in the head and say, 'You better call your uncle and go to work because you are obviously not fit for school.' You would go to work with your uncle. By the time you were 19, you were earning a man's wage and you found your way into the economy."

When the economy shifted and jobs started disappearing, marginalized people were hit first and worst. And in the late '80s, crack cocaine arrived in Halifax, relatively pure and definitely cheap, and line-driving its way into poor neighbourhoods.

"Families went from: Pop is a volunteer fire department chief, a member of the lodge, a deacon at the church and earning a living and sustaining his family and owning his own home on a traditional piece of property that has been in the family for generations," Wright says, "to a young guy who is hustling for a living and selling a little bit of drugs and has a small stable of girls he's running back and forth to Moncton and Toronto. In one generation."

Now, Wright's social tutorial.

What exists in Halifax's inner city and in African Nova Scotian communities, he argues, is an inverse relationship with criminality. "In white communities, criminality is a detractor to the community. It is a negative economy impact. In other communities, it has the opposite effect. It actually improves the economic welfare of the community."

African Nova Scotians experience higher unemployment rates than other Nova Scotians (14.5 percent in 2011 compared to 9.9 percent overall), have lower average incomes and more low-income households.

In these conditions, crime doesn't merely pay, Wright argues. It sustains families in the absence of social supports that lift people out of poverty.

Crime becomes, Wright says, "earning a living to support your family because you want to make a contribution because you are a grown-ass man and you don't want to be a boy."

• • •

When Richards was little, he would take his basketball out to the Steps and practice shooting it at a horizontal wire running along the exterior brick wall at the end of Jarvis Lane. The wire is still there—a phone line, probably. It grazes the top of Richards' head in the mural.

Richards would stand and shoot the wire while the rest of the Wild 4 sat beside him at the Steps. Shoot. Bounce. Shoot. Bounce. Shoot. Bounce. The MGP version of Sidney Crosby's clothes dryer. The two were born in Halifax 10 months apart.

Richards would bug the guys at the Steps: Let's go to the court, let's go to the court, let's go to the court.

Nah, they would complain, too hot.

So he started coming to the court wearing ankle and wrist weights and gardening gloves and practicing with a weighted basketball. He just needed to improve.

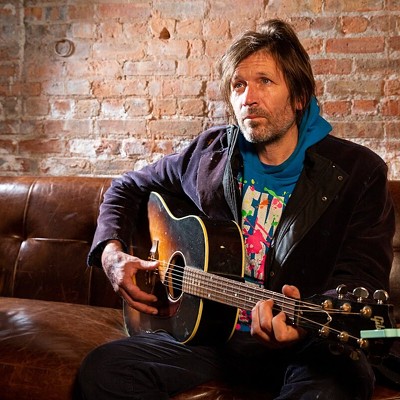

Nathan Thompson remembers people talking about Richards when he was a 10- or 12-year-old prodigy. They said, "You gotta see this kid play."

Thompson grew up in Uniacke Square. He's half a generation older than Richards, and worked with Richards' older brother getting a laptop Community Access Program going in MGP in the early 2000s. He ended up getting to know Richards then, after watching him play ball as a kid.

"His brain was always working when it came to basketball. He was always thinking: how do I get my game better?" Richards had a single-mindedness about basketball that set him apart. Basketball wasn't just his Plan B. It was his Plan A. And his Plan C.

"Failure, for him?" Williams says. "It was not an option."

Thompson played ball, too. If he and his friends couldn't get into a gym near Uniacke, they would hop on their bikes for Saint Mary's, or King's or go sneak into Dalplex. Anywhere they could get in for free.

"Honestly, would I be sitting here today if not for basketball?" he says.

Where he's sitting is in a deep armchair along the wall at Niche Lounge, enjoying an after-work beer.

He calls basketball "the driving force in showing me how to be a man. How to be a productive force in society." He got the same messages at home, but, like any kid, he actually listened to it from his coaches; he spent as much time with them as his parents and grandparents and teachers.

"It gave me a lot of opportunities that I wouldn't have had. It occupied a lot of my time when I could have been doing other things. You know?"

Thompson is a Y Guy—a product of the basketball program at the Community YMCA on Gottingen Street. Many successful Haligonians from the '70s onward have been Y Guys.

Citadel High principal Wade Smith is a Y Guy. He's pushing 50 and he's still a Y Guy. Why? Because once a Y Guy, always a Y Guy.

"This is how we roll," he says. "We are good men first. We are good basketball players second. The program was built on those expectations."

Nathan Thompson wasn't destined for a career in ball. He studied systems management and networking and is now a manager at Web.com. "A lot of the things I learned through sport, I take to my job," he says.

Richards was a Y Guy. A ceaseless mentor to young players. When he died, he was working on a basketball drills book for some of the Needham night hoops kids. Not getting paid. Just doing it.

Thompson thinks he could have been a great teacher.

But basketball was always Richards' goal.

• • •

In junior high and recreational league, Richards never lost. OK, yeah, that's anecdote. Maybe exaggeration. But he was a consistent leader on consistently winning teams. He hit St. Patrick's High School going on 15 in 2001. He was still scraggly then, his deltoid muscles not yet the cantaloupes they would become. He led the team to Nova Scotia provincial titles three years running. He was All Canadian in Grade 12—one of the top high school basketball players in the country.

"He was one of those kids you loved to coach," says Irvine Carvery. "Listened well, made corrections, quick learner, very athletic."

Carvery was Richards' high school coach at St. Pat's, but just like everyone else in the Halifax basketball universe, he had known him forever. "Since he was a tot."

Richards knew his athletic accolades were good. He also knew they weren't good enough to get him where he wanted to be.

"You need to be in school. You need to focus," Williams says Richards would tell kids who looked up to him, tell his friends, tell anyone who would listen. "It don't matter how good you are at ball, you can't go nowhere unless you're good in school."

Citadel High's Wade Smith, a vice principal at St. Pat's during Richards' time, says Richards spent his entire Grade 12 year studying for his SATs (a standardized test for admissions to US schools). "Nobody told him to. He did that to keep his options open."

Richards would shoot at the wire. The MGP version of Sidney Crosby’s clothes dryer. The two were born in Halifax 10 months apart.

tweet this

As an educator, Smith held Richards up as a role model for other students. "He was what we wanted kids to be. He was talented, he was charismatic, he was a good listener, he played hard, he was a good student. He did all the things we expected."

St. Francis Xavier University, in Antigonish, has a history of attracting some of the province's best high school players. But they can't play unless they have the grades, coach Steve Konchalski reminds me.

Konchalski is in his 42nd year at St. FX. He came to Nova Scotia in 1962 from Queens, New York to attend Acadia. More than half a century in Canada hasn't stripped him of his accent.

Konchalski is heavily involved in recruitment. He's known a lot of kids. "Everybody knew about Tyler," he says. "Outstanding player. Exemplary student athlete."

Richards was accepted to St. FX for the fall of 2005, on a basketball scholarship.

Richards succeeded because of his own insatiable drive and the strong circle of support that wound round him. He also succeeded not because of, but despite, the system he was in.

• • •

In the Halifax Regional School Board, black students are suspended more than their peers. Not all students self-identify by race, but for students suspended in the 2014-2015 school year who did, 18 percent were of African descent. During 2015-2016, it was 22 percent.

But only about seven percent of HRSB students self-identify as black.

Black students are over-represented when it comes to Individual Program Plans, too. IPPs are adjustments in learning goals, set when kids can't meet standard outcomes. In January 2015, there were 2,341 students in the HRSB with an IPP. And 273 self-identified as being of African descent. That’s 11.7 percent. [Correction: This statistic was changed from 42 percent to 11.7 percent December 13. Here's why.]

Again—only seven percent of students are black.

According to the 2014-2015 province-wide Grade 8 test scores, only 58 percent of African Nova Scotian students were at or above grade level in reading. Other kids were 76 percent.

Only 31 percent of African Nova Scotians were at or above level for math. For other kids, it's 58 percent.

And of the 494 students enrolled this school year in at least one HRSB International Baccalaureate class, a standardized program for high school high achievers, 20 have self-identified as African Nova Scotian. Four percent. Demographically, too few.

"You look at these numbers and you look at our beautiful and brilliant kids and it doesn't match up," says KelleyAnne Malinen. "Clearly, the school system is doing this to black children."

Malinen is the white mother of a brilliant black daughter. Those are her words. She's also a sociology professor at Mount Saint Vincent University who helped form BlackSPAN, the Black Students Parents and Allies Network, an education advocacy group working to strategize ways to help stop the system from fucking up black kids. (Those words are mine.)

Social worker Robert Wright explains school as culture—to succeed in it, you have to understand it, connect with it and be well socialized in it. And school culture, like all culture, follows the dominant tradition. Here, that means white. And don't kid yourself that it's neutral. It's white.

African Nova Scotian students entering school, he says, "come from an environment of love and nurturing, where they are valued and understood in their racial and cultural peculiarities, and they go into a school system where they are foreign."

This isn't just about too few black teachers and principals. It's about reading materials and visual aids and classroom culture and history lessons and field trips. It's about everything that makes up the school day.

"You have got white people, talking to you about white things, all day long, in a white way, in a white setting," Wright says.

Seth Glasgow is a student in the Nova Scotia Community College Radio and Television Arts program and a member of BlackSPAN. He went to four schools in the Halifax Regional School Board.

"I can count on one hand how many black teachers I had. I was disconnected. I wasn't learning."

He was put on an IPP in Grade 5. He doesn't remember being told, he just knew he was getting different work in math and science. "In junior high," he says, "I was literally getting math sheets I could remember doing back in Grade 3."

In a review this year, the Department of Education found some IPPs for African Nova Scotian learners had been enacted without proper documentation. More than half were not being monitored or reviewed.

BlackSPAN member Tina Roberts-Jeffers thinks about the African Nova Scotian achievement gap this way: "What if, for no reason—they can't tell you why, they can't give you an explanation—seven out of every 10 blond-haired children were not doing well. Is your response is going to be: 'Well, OK, I guess the parents just need to do more to support their children?!'"

• • •

Yet as much as this was the school culture Richards waded into, this is not his story.

Richards didn't seem affected by the barriers many African Nova Scotian learners face, nor held back by them. He was unbothered. Or he overcame. I wish I could ask him which it was.

Because, truly, it would be as ridiculous to assume every African Nova Scotian is affected by these barriers in the same way—or at all—as it would be to assume systemic racism in the education does not exist.

Lenore Black pulls out a tabloid sheet of newsprint, folds fraying, desiccated Scotch tape on the top and sides. "I thought this morning, I'm going to get this thing laminated."

It's a page from the November 11, 1994, North End News, featuring a full-page story on St. Joseph's-Alexander McKay Remembrance Day work. Richards was in Grade 3. His poem leads the full-page coverage—"Once there were men who thought of us. They fought for us..."

He got the pull quote, too; certainly wasn't his last interview.

He said, ‘People are getting killed and shot.’ He said ‘People pull the trigger on nothing. That’s not what I want to be in. I don’t need that.’ —Will Donkoh, Richards’ St. FX teammate

tweet this

Today, Black sits behind her desk at Sir Charles Tupper School. Canada Notebooks and travel mugs scattered on her desk. It's the same room where she got the news Richards was dead, about a minute before welcoming in her students on that cloudy Monday morning. "I was sick to my stomach," she says. "Your little students are never supposed to go before you."

Black (back then, Ms. Paul) was a new teacher in the early '90s. She taught Richards for three years at SJAM. Not only was he a solid student, but her "go-to kid."

"Incidents would happen and Tyler would always be the one who would run to get a teacher or a back-up adult."

Black knew Richards' mom, Janice, well. Janice was supportive at home and involved at school. "I was a repeat teacher, and the third time I had him, she was still" at parent-teacher meetings. She would attend Richards', and other students', birthday parties. She'd go to Janice's place for dinner. Meet for coffee.

She never met Richards' dad, but someone pointed him out to her at the visitation.

Black kept tabs on Richards throughout his school career and into university and made sure she was there to see him play ball in Halifax. She'd often sit in the stands with Janice.

"What I saw for Tyler was a positive role model. I didn't see the other side of that equation. Going to X games and Rainmen games, I saw what I wanted to see and I saw what he wanted to show me."

• • •

Another one of Black's students, Richards' basketball doppelgänger and a member of the Wild 4, was Christian "T-Bear" Upshaw.

Upshaw can't remember a time he wasn't friends with Richards, who was one grade ahead of him. Upshaw grew up in MGP, played on the Steps, played on the same teams. He was a Y Guy. And he followed Richards to St. FX, too. When Richards was in first year at St. FX and Upshaw was finishing Grade 12 at St. Pat's, he messaged Upshaw non-stop: "How's school? What are your marks like? Did you talk to your guidance counsellor?"

Upshaw sits in his Calgary bedroom. His walls are painted chalkboard black; covering them, a mess of words, big and small, equal parts errands and inspiration.

At the end of high school, Upshaw had to upgrade to get into St. FX, going back to high school for a semester. Richards was upbeat about it, telling his friend: "You get another chance. Most people don't get another chance. I didn't find school easy. I just knew what I had to do to get to where I wanted to be."

This wasn't the first time Richards had encouraged his friend.

Upshaw was expelled from elementary school. In junior high, he was suspended repeatedly.

"T-Bear was a little shit," says Wild 4 member Michael Williams. "Double-check with him, but he was the kid who was tipping bookshelves on another kid at Highland Park." (Upshaw: Uh, yep.)

"I was on the verge of going down a dark path, that's for sure," Upshaw says.

Richards would drive Upshaw crazy, nagging him to try out for the Highland Park Junior High basketball team. Then nagging him not to ditch practice. Nagging him to stay in extra-curriculars. Nagging him to go to the gym. "He was like: What else are you going to do? Be out on the streets with the older guys?"

Together at St. Pat's, they won two provincial championships. After Richards went to St. FX, Upshaw won another. Like Richards, Upshaw was named high school All Canadian—one of the best players in the country. (On the side, he was a two-time 100-metre sprint champ and a football wide receiver. He says it like, meh.)

At St. FX, he was named back-to-back Male Athlete of the Year, back-to-back Atlantic University Sport MVP and Canadian Interuniversity Sport All Canadian. After he left St. FX—he didn't graduate—Upshaw played for the Halifax Rainmen, the Moncton Miracles and the Calgary Crush, one season each.

The Crush released him in 2014. He decided to stay in Calgary and study to be an electrician. No more competitive basketball.

"It controlled my life for 25 years. That was everything I did. Everything was solely based on basketball. It felt good to not have that anymore."

New Plan B.

• • •

Richards, Upshaw says with a little wince, kind of lost motivation at the end of university.

The pair had always been together in the summers—as kids, as young men, running basketball camps, or working down at the dockyards with Upshaw's uncle. After his first year at St. FX, Upshaw stayed in Antigonish to work on his game. For Richards, the pull of family, of MGP, won out.

"He was not staying in Antigonish. He wanted to be around his mom and he was on the verge of having a little girl," with partner Le'Kiesha "Flash" Smith. "He kind of had to be home."

After that summer, Richards came back to school and garnered his third consecutive first team all-star award. But at the end of third year and going into fourth, something switched.

"He was still a dedicated basketball player, but changes were occurring," says St. FX coach Steve Konchalski. "Eventually I had to sit down with him and his family to try to get him refocused on university. He wasn't getting into any trouble, but you could see that his focus wasn't there. He was getting involved with people in Halifax, possibly getting involved with some drugs."

Richards stayed on the X-Men all year, a dedicated player who remained academically on track and playing, in Konchalski's words, "at a very high level."

He returned for his fifth and final year at St. FX in 2008-2009 and he again took all-star and finished his AUS career with the second-highest points total in St. FX history.

It was Will Donkoh's first year with the team.

Donkoh was an Ottawa native who was arriving late to pre-season training. Richards was the first to introduce himself, in meal hall. Sometimes, Donkoh says, it's the weirdest little things you remember about someone: "He put a lot of salt in his food. He put it in everything he ate."

They became fast friends, playing video games in Donkoh's dorm with his roommate, basketball player Jordan Hope, and another first-year student, Eamon Morrissy.

Richards had a key to the gym change room, so he could practice shooting anytime.

"He would leave us and I thought he was going home, but he was going to the gym. He would spend four or five hours alone. He always spoke about the work ethic, but he wouldn't drag you there. He worked very hard."

On the night of February 21, 2009, the AUS Final 6 tournament was two regular season games away and the X-Men were top-seeded heading in. Richards got into a fight, outside near the hockey arena off James Street. It was chippy, long-coming, messy. Morrissy and Donkoh moved in to break it up. That was the plan, anyway.

"You know those things you wish you could take back?" Donkoh says.

The three were charged with assault causing bodily harm. Two days later, Richards was named St. FX Athlete of the week.

As news of the charges spread, St. FX made the decision to bench the three players for Final 6 playoff games. Richards left St. FX. Left Antigonish. He never graduated. Never went back. He returned to MGP.

"I believe if that hadn't happened," Donkoh says, "we would be seeing a completely different outcome. I think that transition"—for Richards—"into the real world was hard."

Donkoh stayed at St. FX. He now plays pro ball in France, along with his wife.

Coach Konchalski sat through every minute of Richards' trial. He's still in contact with Richards' family. He would only talk to me for this story with Richards' mom's OK.

"Tyler did everything he could to avoid that confrontation," he says. "But this individual wanted a piece of him. And finally Tyler said, 'OK, you want me? You're going to get me.' As with so many of us, our strengths are our weaknesses."

As the school year wrapped up, and Richards should have been getting his X ring, he was convicted of the assault charge. He was sentenced to four months' house arrest. He didn't talk with the Wild 4 about what happened.

That summer, Richards was arrested for breaching a condition of his house arrest—he was found at a party out past his court-mandated curfew. Police had shown up because there was a shooting. The intended target, according to a source, was Tyler Richards.

"He only showed people what he wanted them to see," says Wild 4 member Michael Williams. "If he did this, that's separate from this. Everyone makes choices. He always put the community and those he was guiding first. He was always a positive model."

• • •

And he got his second chance.

In November 2012, Richards' hometown National Basketball League team, the Halifax Rainmen, played its regular season opener with Richards on the roster. He played 31 games as a pro baller before the season closed in March 2013.

Year over year, Rainmen rosters always included a handful of local players and inevitable fan draws. "They didn't play him as much as they should," Nathan Thompson says. "He was a lot better than most of the guys."

NBL players don't make a king's ransom. The league's per-team salary cap is $150,000, which is shared among 10 or 12 players.

It's not hard to do the math. Even if that $150,000 maximum amount is paid out, and even if team members shared that pot equally—which they almost certainly don't: Canadian players tend to earn less than their US teammates, says coach Konchalski—that's a salary of $12,500 to $15,000 per season.

Not enough to keep a family going.

Basketball as a career goal is no different than aspiring to be in the NHL. If players manage to hit the major leagues and the fickle constellations of health and play time align, they can do very well. But relative few make it that far. Most high-level basketball players will reach the NBL or similar international leagues, honing their skills playing the game they love. But not getting rich. Maybe just getting by.

But basketball as a means to something else? That's a well-travelled route. It was Nathan Thompson's path. It was the path of Wade Smith, too, who went to St. FX a generation before Richards.

“You need to be in school. You need to focus,” Richards would tell kids. “It don’t matter how good you are at ball.”

tweet this

Richards was re-signed to the Rainmen in the fall. He played the team's November 1, regular-season home opener, full of promise for more time on the court and a strong showing for the Rainmen.

Ten days before Christmas, Richards was charged with assault against a woman at Taboo Nightclub on Grafton Street. He was suspended without pay from the Rainmen on December 17. The following day, he was arrested on Connor Lane and charged with possession for trafficking and firearm offences. He was released on $2,000 bail. On December 27, the Rainmen let him go.

The drug and weapons charges were later dropped. But Richards was never invited back to the team.

The fact that Richards' Rainmen number—6—is missing from the MGP mural is no mistake.

The mural includes 23, his jersey number from St. FX. But his ID with the Rainmen, the team the wider city would most associate him with, isn't there. The mural effectively writes the Rainmen out of Richards' story.

"What I was hearing was that he felt let down," says Williams. "They said they supported him and then the next day they let him go."

Was the Rainmen organization right to drop Richards? For some, the answer is yes, because the charges indicate a pattern of behaviour.

On the day of Richards' firing, Rainmen owner Andre Levingston told CBC News, "Our players serve as role models in the community and we stand in front of kids every day and talk to them about making the right decisions and staying away from drugs and things of that nature."

For others, it's no. Richards was only suspended on the assault charge, not fired from the team, and the drugs and weapons allegations were dropped.

El Jones, a teacher, poet and member of BlackSPAN, didn't know Richards, but, like so many people, knew of him. "Is he valuable enough as a basketball player, but not valuable enough to try and save?" she asks. "Did anyone have a conversation with him? Were there any supports to help him? Or was he thrown away?"

And, another question: "How can somebody be so successful and embody everything [they are supposed to] and still not get the help and support they need at the point where they need it?"

• • •

Before the season that Richards abruptly left St. FX, Wade Smith sat down with his friend to ask: "What happened, man?"

After he left St. FX, former coach Irvine Carvery talked to him, too.

"I said, 'Tyler, don't let this be the defining point in your life. You have done all the things you need to do. You need to go back to X and finish your degree and good things will happen.'"

Steve Konchalski and his wife, Charlene, up to the last year or so, were working to get Richards to come back and finish his degree. Richards had an open invitation to live with them at their house while he did it.

"We were encouraging him," Konchalski says, "because it's a shame to get that close to a degree and not finish it off. But that's an indication of where his focus was."

In October 2014, Richards was sentenced to one year of probation for the Taboo Nightclub assault. The possession for trafficking and firearm charges were dropped after his co-accused, Marcus Demitries James, plead guilty and was sentenced to two years federal time.

• • •

Richards' run-ins with the justice system were separate from his other self—the positive icon in MGP, the mentor, the volunteer. Local papers covered his court appearances with the same attention they once paid to his on-court appearances, but that other life was unknown, unspoken, among his friends. And, in a sense, unimportant. Half blindness, half blind-eye.

"Growing up in the area and being really familiar with people from the inner city?" says Nathan Thompson. "For some people it's easy money. I could do this, or I could go out and work for 15 hours a day. And sometimes it really comes down to..."

Thompson wells up. Stops for a moment. Pulls it together.

"It's really choices," he says.

Coach Konchalski received calls after Richards' death about how much time Richards had put in working with kids, and how many were interested in pursuing degrees because he showed the way.

"There was a side of him—even though he was involved in less than above-board activities that cost him his life—he was still contributing in positive ways to society, to his community. That's the sad part: He had the ability to do that to a much greater magnitude. To help young people to a greater degree."

Citadel High principal Wade Smith rubs his forehead.

"No one really wants to sit down and talk about the gory details of a guy who you loved. When I spoke at the funeral, all I could really say is: People make choices and choices have consequences. I say it to every kid who comes into this office. You don't go to the funeral to talk about the gory details. You go to talk about the good things and try to hold onto that."

Richards was sliding into home plate on his degree, with good options for pro ball or a job. After the fight at St. FX, those options started to crumble.

It's easy to tell someone to pick himself up and keep going; much harder to do it.

Upshaw adds: "Where we're from, it's hard for kids to dream to be specific things, because you can't expect a kid to want to be a doctor if no one has ever been a doctor from there. If no one's ever been a lawyer. These kids? They don't see these things. So they aren't going to dream to be these things."

In this, lies the meaning of the mural—Richards as angelic, stoic, protective. In MGP, and to his friends, Richards' faults aren't the dominant narrative. They aren't something people need to know or had to know or, frankly, want to know. Upshaw says, "He did way more good than he ever did negative." And for people who don't know that side of Richards? "They are going to think: Another danger off the streets."

Why did Richards make the choices he made?

The only person who can answer that is Richards.

So, a new question: Do a man's worst choices outweigh his best ones?

And when it comes to black men in Halifax, specifically, doesn't it seem so often like the negative choices mean more, and the positive ones get left out altogether?

• • •

There was a murder in Halifax the summer before last.

Dalhousie student Taylor Samson went missing in August 2015. Soon after, William Sandeson, another Dal student, was charged with first-degree murder in his death.

Samson's body has never been found. According to court documents, his mother told police that her 22-year-old son sold marijuana on the side for extra cash while he was a student. Police allege he was the victim in a drug rip—a robbery gone dreadfully wrong. Samson was a physics student and fraternity member. The accused, Sandeson, then also 22, ran track for Dalhousie and represented Nova Scotia in the 2013 Canada Games, winning bronze in the 4x400m relay, and was arrested days before starting his first year at Dalhousie medical school. Both white. The trial will be held in Nova Scotia Supreme Court in spring 2017.

Samson's mother and girlfriend have confirmed his involvement in the drug trade. Trafficking allegations against Sandeson have not been proven in court, but police are relying on the drug rip theory as the launching incident behind the murder.

So, these are guys getting by. Right? I mean, isn't that how you think of it? These aren't drug kingpins. They are average guys, like the scores of other average guys, selling drugs—probably to fellow students—for pocket cash.

Nobody is talking about a city-afflicting network of drug-dealing Dal students. No one is talking about violence wracking the south end, about the depravity of the physics department, nor the dangers of medical students.

"No one says: What's wrong with Dalhousie? Is it criminal? What is that environment teaching people?" El Jones points out. "We just say: It happened. It's tragic and it's unfortunate and it happened."

But it's different for African Nova Scotians.

"When it comes to the African Nova Scotian community," Robert Wright says, criminality is "seen as much more dangerous and insidious and dark."

Wright reminds: This is the province of the BLAC Report and the Marshall Inquiry. A province where the premier has acknowledged systemic racism in his apology to the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children residents. A province where systemic discrimination is writ large.

Our society, BlackSPAN's KelleyAnne Malinen says, "has an easier time seeing a victim who is white...or, understanding the humanity of a perpetrator who is white."

Research suggests black children are often read as older than their ages. "We don't see vulnerability in black children," Malinen says.

Of the 12 murders in Halifax so far in 2016, more than half were African Nova Scotian men. Demographically, that's out of whack. Statistics Canada's 2011 National Household Survey counts Halifax's African Nova Scotian population at 3.6 percent.

Constable Dianne Woodworth of the Halifax Regional Police says the tally is protected under the Municipal Government Act, which prohibits the sharing of personal information. An exception to the act is allowed when sharing identifying details is considered to be in the public interest—specifically, from the act: Mitigating a risk "to the health or safety of the public or a group of people."

"How many black men have been shot, or have shot someone in this city?" asks social worker Robert Wright. "If we are not at epidemic proportions yet from a population health perspective, then I don't understand population health."

Violence is followed, often, by targeted policing. There was an uptick in police presence in the north end in the days following Richards' murder and the shooting two days later on Gottingen Street of Richards' cousin, Ricardo Whynder, and Naricho Clayton. Whynder was injured. Clayton was one of those names of the dead for 2016.

"What about education?" asks BlackSPAN's Tina Roberts-Jeffers. "What about health care? What about children and family services? These things wrap around and it's left out of the conversation so often.

"It doesn't make sense to talk about violence and not talk about the ways black people are denied access to capable employment and wages. It does not make sense to me to talk about violence and not talk about an education system that, clearly, on every single level, is failing black children."

El Jones calls it structural violence. And you can't arrest your way out of it.

Detective Jason Withrow can't talk about the specifics of Richards' case, but he calls witnesses the most important element police have in solving difficult major cases.

"Often, we know what happened, but we don't have it in a way that we can take it to court." Withrow says sources won't talk because they don't like police, don't want to be labelled a snitch or fear retribution.

"We call people and we get hung up on and that's just part of it. Sometimes people will talk to us, but they won't say what they know."

If there's a disconnect between the police and some communities they serve, that divide reveals itself in other parts of the city, too. Robert Wright gestures out his office window to passing boats and sun flecking off the harbour. "You go in the summertime and you walk around downtown. If you see a middle-aged black couple holding hands walking down Lower Water Street, there is a cruise ship in town."

Does Halifax ever ask itself why?

And has the city really asked itself, in the months that have followed Richards' murder, how this could have happened to a guy like him?

• • •

A week before Easter this year, Richards was pulled over in a car on Walter Havill Drive, with two others. Police charged him with trafficking, possession and breach of probation. He was due in court on May 9. He never made it.

• • •

Michael Williams slides his phone in front of me.

"This sums up Tyler."

In the photo, Richards towers over a boy, maybe eight years old, a ratty basketball net in the air between them. "This is him," Williams says, pointing to one of the children at Needham night hoops and back at the phone.

The photo was from last summer.

"That was Tyler all the time. A teacher. An educator. That was him. If you knew Tyler, you knew that."

Former teammate Will Donkoh got a call from Richards in the fall. It was one of those calls any of us might receive and never think about again, but which in hindsight takes on amplified meaning.

"He was as clear-minded and ambitious as I have ever heard him," Donkoh says. "He said, 'People are getting killed and shot.' He said, 'People pull the trigger on nothing. That's not what I want to be in. I don't need that.'"

They chatted a bit more, reminiscing about St. FX days, and said goodbye. Later that night, they met up for a drink and a bite. Donkoh never saw him again.

• • •

The night Williams got the call that Richards had been shot, he bolted out the door for the hospital. His drive was interrupted by a call from a mutual friend, Kal, who told Williams, "He's gone."

The next morning, he knew he had to go to the Steps.

He grabbed a few pictures and some flowers and drove to MGP. As he got out of his car, Williams spotted his mom walking up the Steps after checking in on Richards' mom. He broke down.

And as he says it, he breaks down again.

She helped him tape the flowers in their cellophane wrap to the handrail of the Steps. They taped up photos beside them. More flowers followed, along the wall where Richards used to shoot the ball at that horizontal wire while the Wild 4 told him to quit it, already. And Richards would just shoot and shoot and shoot. Soon there were more posters and candles. Someone brought a 50-pack of Timbits.

"Just seeing the people coming through," Williams says, "knowing where they were coming from, it was special. It blows your mind, because I knew he had a big impact, but I didn't know it was that big.

"It wasn't meant to be a memorial or anything. It was just, you are loved. You are missed. This was us."

Correction made December 13, 2016: The original version of this story stated that in a random sample of 292 IPPs from March 2015, the HRSB found 124 were for students of African descent, totalling 42 percent. In fact, while source documents call the selection “random,” it was skewed to purposely include a higher percentage of African Nova Scotian learners. The true percentage of IPPs for students of African descent is 11.7 percent. Click to go to that point in the story.

Lezlie Lowe is a freelancer, journalism instructor and contributing editor at The Coast. Follow her @lezlielowe.