click to enlarge

TED PRITCHARD

Premier Stephen McNeil on election night.

Politicians of all stripes love to talk about transparency. They praise it, they throw around buzzwords like “

open by default” or, in the direct words of Stephen McNeil, promise to make Nova Scotia “

the most open and transparent government in the country.” None of these promises

mean much if you don’t read the fine print associated with them. There are nearly always exceptions, loopholes or bureaucratic tricks which ensure

that, even where information is technically open, in practical terms it remains off limits to the public.

click to enlarge

SUBMITTED

Michael Karanicolas is a human rights advocate who works to promote freedom of expression, government transparency and digital rights. You can follow him on Twitter at

@M_Karanicolas and

@NSRighttoKnow.

The most recent case to hit the headlines involved Dalhousie University, which faced an information request from the Canadian Union of Public Employees about the number of full-time and part-time faculty at the school over the past decade. Although legally required to respond to the request, the rules around how much they can charge are more difficult to enforce. The university

demanded $55,000 for the information, claiming that it would take 1,845 hours to complete the request. While the information commissioner has said this is the biggest estimate she has ever seen, it is by no means an isolated case.

Last year, I was contacted by a journalist from Cape Breton who

sought expense information for the mayor and five CBRM employees and was told it would cost $42,804.50 to deliver the information. In both cases, the requesters are technically allowed to access the information, but that right is not worth very much in practical terms.

In addition to exorbitant pricing, another common challenge

is delays. Across Canada, our freedom of information systems

are notorious for their backlogs. A request for files from an RCMP corruption investigation came back with an estimate that the information would take

80 years to review. Earlier this year, the Canada Border Services Agency

decided that the best way to deal with ballooning backlogs in their access to information system was to ask requesters who had been waiting years to

simply abandon their requests.

Even where information is made available, there

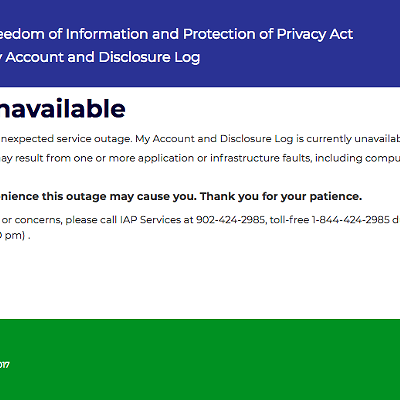

are a range of technical or accessibility challenges which can still put it out of people’s reach. A recent study found that Nova Scotia’s public tendering website was

riddled with broken links. The province’s FOIPOP portal has been down for months

now, after its shoddy security led to an infamous breach earlier this year.

And of course, the ability to get your hands on any information about what the government is up to depends on them leaving a paper trail in the first place. In 2016, Stephen McNeil told reporters that when he has to do sensitive policymaking work, he

prefers to use the phone, in order to ensure that there are no records that the public might later request. Nova Scotia’s former finance minister claimed that the

use of private email accounts was rampant for the same reason. The premier has brushed aside calls from the information commissioner to institute a duty to document, which would require officials to leave an official record of their deliberations.

All of these are hallmarks of a broken system. Accountability and oversight are never

pleasant, and given a choice, many people would rather avoid them. But that’s not how democracy is supposed to work. Transparency systems are a lot like the tax code: You have to design them under the assumption that people will try and cheat, but to make it as difficult as possible to do so. These examples show that there is much more work to do. Nova Scotians need to demand better.

———

Opinionated is a rotating column by Halifax writers featured regularly in The Coast. The views published are those of the author.