News of Justin Trudeau’s election win in 2015 on the back of his campaign promise for recreational cannabis legalization inspired the same starry-eyed fever in Canadian entrepreneurs. For those swapping traversing vast planes on horseback for navigating rigid government regulations, one thing is sure: Green is certainly the new gold.

As Canada flings itself towards cannabis legalization later this year, Nova Scotia growers and producers—late bloomers they may be—are trying their best to bulldoze through the bureaucracy. Thirty Nova Scotia companies have spent some part of the last five years in licensing limbo. With 2,000-page applications, a federal regulator wielding god-like power, the looming presence of money—lots and lots of money—and no map to guide them, it’s a miracle half are still standing.

Back in 2001, the year Canada legalized medical cannabis, Andrew Robinson enrolled in one of the first cannabis agriculture programs in the country at Dalhousie’s Agricultural Campus in Truro. He thought he was too late, that the federal government would permit recreational pot hot on the heels of allowing medical, and commercialization would take off before he graduated.

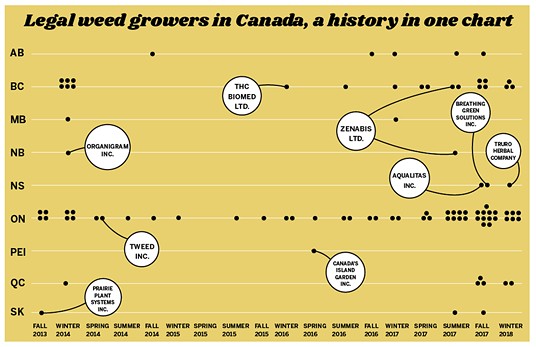

Luckily for Robinson, now president and master grower of Robinson’s Cannabis in Kentville, rec legalization is taking its sweet time. Canada didn’t have any medical cannabis licensed producers (LPs) until 2013; Nova Scotia’s first license wasn’t issued until November of 2017; and with the original goal of July 1 becoming politically unfeasible, there’s still no official date for national recreational legalization.

According to Health Canada, as of April 5, Nova Scotia has three LPs—a measly three percent of the national total. (Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nunavut, Yukon and the Northwest Territories, are Canada’s only jurisdictions with none.) Robinson’s Cannabis is one of Nova Scotia’s 13 would-be producers stuck in licensing limbo, and a similar number of NS applications have been rejected.

The province’s slow start is surprising if you consider the fact that Nova Scotia has the nation’s highest per capita consumption of cannabis, according to StatsCan. It’s less surprising if you consider that fro-yo took off in Nova Scotia about five years after every other province in the country, and there’s still no Uber.

In Canada’s easygoing Ocean Playground, the government is often hesitant to dive into new things. Myrna Gillis, CEO of Aqualitas, Nova Scotia’s third LP, says the province’s attitude is similar to the way she likes to introduce new cannabis consumers to the product: “Low and slow to start, and it will evolve.”

“The way I look at it is that this is incremental,” Gillis says. “The desire is to take a slow and cautious beginning, and that’s fine.”

But just across the border, Nova Scotia’s provincial frenemy is moving quickly. New Brunswick has planned a fund to support cannabis research and the development, is getting into the recreational pot retail market with 20 “stand-alone” shops separate from existing liquor stores and, in 2016, invested $4 million in Zenabis’ weed growing facility, which received its license last year.

To Andrew Robinson, these initiatives are “fantastic,” and leave him all the more “puzzled” by the Nova Scotia government’s hesitation to join the green rush. "I really don’t understand why they are so in the dark, so behind the times,” he says. “They are just so stubborn."

It’s hard to know what the market for weed will look like on legalization day, whenever it arrives. (The most-repeated refrain coming out of Ottawa has changed from “by July” to “before October.”) But Robinson thinks Nova Scotia, with only nine retail stores planned so far, has vastly underestimated demand.“In the United States after legalization there were lineups down the road—and they had stores on every block,” he says.

The provincial government hopes that online sales—akin to the way patients buy cannabis in the tightly regulated medical cannabis market—will make up for any lack of stores, while it waits for the smoke to clear before making further infrastructure plans.

Meanwhile, the small team of Nova Scotia Liquor Corporation staff assigned to the cannabis file appears to be doing the best they can with what they have to get ready for legalization. In January, they reached out to growers in the province and across Canada, and have 35 producers—licensed or in processing—interested in selling pot in Nova Scotia.

“We are enjoying a very collaborative relationship with licensed producers,” says the NSLC’s Beverly Ware, “highlighted by open and transparent dialogue on both sides.”

With only three LPs, all of whom are still waiting for their retail license, there’s not going to be much—if any—local bud on NSLC shelves, though Bill Sanford of Breathing Green Solutions, the first producer in the province to get its production license, is confident his company will be ready. “We’ll beat the recreational date,” he says. “I’m not worried about that.”

THE PROCESS

The blind lead the blind

As the Cannabis Act, Bill C-45, makes its way through the gauntlet of politicians debating and deciding and then deciding differently, Health Canada has emerged as the department responsible for pot production. The department’s almighty power has given plenty of producers reason to worry, but not enough to stop the willing from giving it their best shot.Of the 1,861 applications for a cannabis production license Health Canada had received by February 1, half of the best-shots weren’t enough to make it past the first checkpoint. Of those that made it into the queue, 38 percent were subsequently either refused or withdrawn.

In a nationwide experiment of the blind leading the blind, growers are surrendering the power, holding on tight and hoping to make it through to the other side. Crossing their fingers, hoping to find the gold of pot at the end of the rainbow.

“Unlike many other businesses where you control your own destiny in terms of how quickly you can get things done,” says Breathing Green’s Sanford, “you don't control your own destiny in this case.”

As the pressure mounts to get ready for recreational legalization this summer, Health Canada has been—as you do when you’ve never

Producers are trying their best to keep on top of the fast-developing rules and regulations, and the regulator keeps trying to meet them in the middle. "Just when you think you’re getting everything finalized, things change and you have to keep constantly improving," says Andrew Robinson.

Robinson’s Cannabis is just one of 476 Canadian growers wading through this licensing layaway. It’s just recently received a “confirmation of readiness notice” giving clearance and the go-ahead to build its facility. A Health Canada inspector will come do security checks, and if everything is perfect, give the cultivation license.

This is a new step, part of the fluctuating rulebook balancing due diligence and demand. "They used to not give the cultivation licence until the first inspection, but now because of so many companies and so few inspectors, they're giving the cultivation licences in advance,” says Robinson.

The regulator’s list of requirements is incredible. The 2,000-page application tomes require details on security clearances for anyone who will be in a room alone with cannabis plants, intricate explanations about planned cultivation method and notices to local government, police and fire authorities, to name a few. And that’s just step one.

Once a producer is licensed to grow, it has to do two separate “crop runs” and have its product inspected by Health Canada before it’s granted a license to sell.

Breathing Green Solutions’ official application was submitted to Health Canada in 2015, but to save time the company gambled and built the facility before approval. The risk paid off and Sanford credits the completed high-end facility with helping Breathing Green move up in the licensing queue.

“Inside the building you see this incredibly pristine environment with more doors than you'd ever need,” says Sanford. "If you go inside the growing rooms with the lights turned on you’d think you were in a huge sun-tanning bed." The growing rooms have 1,000 plants getting their glow on right now, and will have up to 1,500 at full capacity.

Aqualitas started the application process in March of 2015, and also “caught up very quickly,” says Myrna Gillis. Meticulous work and passion has carried her team this far. “There’s no one piece,” she says, “but the symphony of pieces that came together that made it work.”

Aqualitas had a robust team of academic experts from Dalhousie and Acadia universities working with its subsidiary Finleaf Technologies, Inc. to ensure its fascinating aquaponics technology—a growing system that teams up large koi fish with plants, so the fish and the cannabis essentially feed each other in a mutually beneficial cycle—was first class.

Like Gillis, Sanford also credits Breathing Green’s star-studded team with helping navigate the process. That team includes a former RCMP SWAT team leader heading security, an ex-Health Canada quality assurance person, a PhD as the chief science officer, a pharmacist and an experienced family doctor.

Both Breathing Green and Aqualitas are waiting on their retail license in order to sell their product. Gillis says this final step can take anywhere from six to 12 months.

THE MONEY

Giddy-Up, Cowboy

Anybody who’s in the game at this stage got there with a lot of patience, attention to detail and the final green ingredient: Money. No Nova Scotia producer has yet to earn a dime on cannabis sales—medicinal or recreational—but the promise of gold at the end of the rainbow is proving to be promise enough.Investors hungry for a slice of the pot-pie have made for a bit of a “wonky” market says Sanford. Andrew Robinson says they call it “the pot stock munchies.” Statistics Canada estimates the Canadian cannabis market was worth $6.2 billion in 2015, when medical patients were the only legal consumers. Deloitte released a study at the end of 2017 saying the market with legal recreational users could be worth $22.6 billion. Valuations are rising as legalization nears, and companies that have yet to earn a buck can be worth a billion dollars on paper.

“It’s kind of like the Wild West,” says Sanford.

For Nova Scotia’s companies already out of the gate, they’ve even had to turn people away.

“We actually do have people just sitting on the sideline with a million dollars waiting to invest," says Robinson.

It seems unbelievable that companies would be turning away people waving million-dollar bills, but private companies are limited in the way they can receive investment, and many of those that already met their goals are waiting out the process before taking any more cash.

Part of Nova Scotia’s slow start in the industry comes down to lack of access to capital. Private companies can raise money three ways: Investment from friends and family, investment from accredited or “angel” investors and the little-known investment by offering memorandum.

Angel investors are people with a lot of money. (They either make over $200,000 a year or have $1 million in ‘liquid assets’ that aren’t property.) Angels who have money get to give money where they know they’ll definitely make even more money.

Aqualitas is one of only two cannabis companies in Canada that raised funds through an offering memorandum. It allowed investors to come from diverse backgrounds, and avoid what Gillis calls “a perpetuation of wealth.” By allowing people to invest as little as $10,000, Gillis says the money raising is more “organic,” just like Aqualitas’ plants.

From Nova Scotia, it’s easy to look to New Brunswick’s shining example and wonder if producers, and their investors, would be better off moving out of province. Robinson says that if Nova Scotia’s government supported the cannabis industry like New Brunswick does, “it would be a game changer.”

But true to form, producers concede to Nova Scotia’s final sticking point on progress: Stubborn Nova Scotian pride.

The majority of Breathing Green Solutions’ 80 friend and family investors are Maritimers. Gillis says Aqualitas “wanted regular Nova Scotians to invest in our company if they wanted.” Asked if New Brunswick would have been a better bet, Robinson answers: “I’m from Nova Scotia, I really love it here. But I’ll tell you one thing, my investor sure thinks so.”

Beyond the immediate rush to get laws and a retail pot system in place, Gillis, Sanford and Robinson are excited for what the cannabis industry will look like in a couple years. From oils to edibles, hybrids and “craft grows,” they’re taking inspiration from the province’s booming wine, beer, cider and spirit industries. They’re confident it will be worth the wait in green, and maybe even gold.

Caora McKenna is a Halifax journalist and The Coast’s copy editor.