Picture this: You’ve just returned from an early November stroll through Point Pleasant Park or the 12-kilometre in-and-out trek to Cape Split when you notice you’ve got unwanted company. Is it a freckle? A mole? Wait… are those legs? You begin to spiral. Oh, god, it’s an alien. Nope. It’satickitsatickitsatick.

You manage to pry it off—how deeply was it buried in there?—only for the next round of spiraling thoughts to begin. How long has it been there? Was it from today’s hike or yesterday’s? Should I be going on antibiotics?

That’s a scenario we could very well see more often in Nova Scotia as balmy weather lasts into the latter months of the year, according to Nicoletta Faraone, an assistant biochemistry professor and chemical biologist at Acadia University.

“With global warming and climate change, we are going to see the rise of vectors and vector-borne diseases,” she tells The Coast.

And as the province sees a prolonged stretch of weather in the mid-to-high teens into November, that means blacklegged ticks—the species responsible for transmitting the bacteria that causes Lyme disease—are still out and feeding.

Calgary is getting buried by snow right now, but the 10-day forecast for Halifax features more of the “humid and pretty mild” weather that Faraone says ticks thrive in: “This is basically the best environment for them.”

‘There are ticks out’

Nova Scotia is a tick hotbed—that much, Haligonians already know. The province has the highest tick-to-human ratio in Canada, and the second-highest number of ticks in the country after Ontario (which is so overrun with the pests, Ontarians opted to elect one as premier).

There are 14 types of ticks found in Nova Scotia, but only the blacklegged tick transmits the bacteria that causes Lyme disease. Blacklegged ticks first appeared along the South Shore, but have since spread as far as Cape Breton.

“Pretty much everywhere in Nova Scotia is bad for ticks, and bad for Lyme disease,” researcher Vett Lloyd, director of the Lloyd Tick Lab at Mount Allison University, told The Coast in August.

Thanks to milder winters, the species is only becoming more prevalent. An adult female can lay “about 3,000 eggs” after a blood meal, according to Lloyd, “so that means the population could go up and up very quickly.

“In the past, the cold winters have killed off a lot of the the young ticks because they're a bit delicate, but the winters aren't as cold, the snowpack isn't as deep, and so more of those babies are surviving to get their own blood meal and make their own 3,000-odd ticks.”

Cold weather and Balsam fir needles may be key for tick control

Blacklegged ticks are Goldilocks-like, Faraone says—their preferred environment can’t be too hot or too cold. The ideal temperature, she adds, is usually above 4 C and below 25 C. In Halifax, that can last anywhere from March until late November.

But with such “unusual, warm climates” stretching into late fall, Faraone adds, it has created “basically the best environment for [ticks] to thrive and to be active. So if we go for a hike, we have a high probability of encountering a tick.”

If there’s hope for killing the nasty buggers—er, that is, reining in Nova Scotia’s tick population, it may well come in the form of a tree species already abundant throughout the province.

A recent study led by Dalhousie University neuroscientist Shelley Adamo found Balsam fir needles and their essential oil kill ticks at colder temperatures—and may well prove a worthy substitute for pesticides that can have other harmful consequences on their environment.

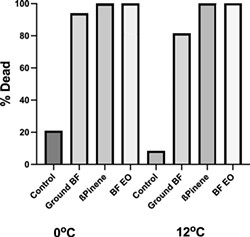

Adamo and her colleagues at Dal and Acadia University (including Faraone) collected “hundreds of ticks” over the course of three winters, she told CBC Radio’s Mainstreet Nova Scotia in August. In both lab and outdoor environments, they exposed blacklegged ticks to both Balsam fir needles and their essential oil, and compared the ticks’ survival rates to those left in a more tick-preferred winter environment of oak and maple leaves.

The ticks’ survival rate in maple and oak leaves “was sometimes 60%, sometimes 80%,” Adamo noted, whereas their survival in Balsam fir “was basically zero.”

She believes the winter season, with its colder temperatures, could be an overlooked opportunity for tick control measures: “Obviously, there's no food for them. So it's a very stressful time. And that means it's a time of opportunity to get rid of them because they're already under stress. It might not take much to push them over the edge.”