Charlotte MacDonald’s Chebucto Road apartment was small, but she loved it anyway. Three blocks from the Halifax Commons, she could grab a coffee on Quinpool, stroll over to the North End for a bite or saunter to Spring Garden Road within minutes. All for less than $900 a month.

“I never had to take the bus anywhere,” she tells The Coast.

The Christ Church Halifax lot across the street meant free (if not fully sanctioned) parking. Her friends were nearby, and her building neighbours were friendly. She was on good enough terms with the superintendent to trade plants. Things were comfortable.

“It was a good neighbourhood,” she says. “There was a good sense of community.”

MacDonald had been in her bachelor suite for three years—longer than any other home in her adult life. It was the first apartment she’d rented on her own. She imagined she’d be there for longer still.

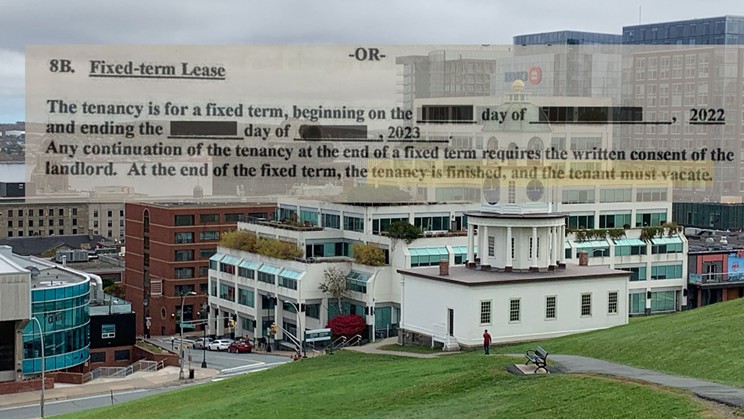

Only, despite her wishes, she’s now gone—and the building neighbours are too. She was on a fixed-term lease—defined in Nova Scotia’s Residential Tenancies Act as a rental agreement with a predetermined end date, as opposed to periodic leases which roll over on a monthly or annual basis.

MacDonald’s landlord, after earlier assurances that she could re-sign a new lease, told her in July she was “going in a different direction.” Unable to afford another apartment in Halifax, MacDonald moved back in with her parents in Cape Breton.

Her old apartment? It’s now listed for $210 a night on Airbnb.

Fixed-term leases growing in popularity

MacDonald is far from the only renter in Halifax to have signed onto a fixed-term lease. If you moved into a rental unit or changed units in the HRM after November 2020, when the Nova Scotia government introduced a temporary 2% rent cap, there’s a decent chance you’ve signed onto one too.

“Due to changes in the Tenancy Act, the industry has moved away from month-to-month leases and moved to fixed term so that both tenants and owners are on equal footing in regards to the terms and options of the lease,” one property manager told The Coast by email.

They’re not a new phenomenon: Fixed-term leases have been written into the Tenancies Act for decades and exist in various forms across Canada. And there are benefits to both tenants and landlords, if both parties agree on when they want the lease to end.

But some housing advocates argue the lease option has become a “loophole” for landlords to circumvent things like rent control—and as the HRM and province deal with a housing affordability crisis reaching levels “never seen before in our province,” they say it needs to be curbed.

‘We’re seeing [lease agreements] being, frankly, exploited’

Of all the walk-in clients Katie Brousseau sees in a day at Dalhousie Legal Aid Service, their concerns are “almost exclusively” about tenancy matters—and often about fixed-term leases, she tells The Coast.

That’s because, as tenancy options go, fixed-term leases offer “far [fewer] protections” for tenants than month-to-month or year-to-year leases, she says. Unlike periodic leases, which roll over when they reach their term end (say, at the end of a month or year), fixed-term leases don’t—which means tenants are left without any security of tenure. If a landlord wants a tenant to leave at the end of a fixed-term lease, “they’re not obligated to have a reason,” Brousseau says.

“So it makes it very difficult for folks on a fixed-term lease to know whether or not they'll have a continued tenancy.”

That level of flexibility works out well for property managers, but comes at the expense of tenants, Brousseau argues.

“We’re seeing [lease agreements] being, frankly, exploited,” she says.

In a region with a 1% rental vacancy rate—the national average was 3.1% last year, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC)—tenants have little recourse if a landlord insists on a fixed-term lease instead of a periodic lease, or only offers an eight-month lease through the winter and spring so they can re-rent the unit for tourist season.

And while the province’s 2% rent increase cap applies to fixed-term leases—so long as landlords and tenants re-sign a new agreement—the same protections don’t apply when a fixed-term unit turns over between tenancies. That leads to a “vicious cycle,” Brousseau says, where “tenants are afraid to exercise their rights” for fear of “having no other affordable or accessible housing options.”

Advocates call for loophole’s closure

Nova Scotia’s approach to fixed-term agreements is not wholesale across Canada. Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia have varying bylaws that require a landlord to prove, in good faith, that they or their relatives either intend to occupy a unit—for at least a year in Ontario—demolish it, convert it to something other than residential use or make repairs “that are so extensive that they require a building permit and vacant possession of the rental unit.”

None of those requirements exist in Nova Scotia. Were that the case, Charlotte would still have her apartment.

That’s what housing advocate Hannah Wood would like to see implemented in Nova Scotia. As co-chair of ACORN Canada’s Halifax Peninsula chapter, an advocacy group for low- and moderate-income people facing housing, pay and disability concerns, she has campaigned for more rigorous tenant protections within Nova Scotia’s legislation—and was part of the push for the province’s temporary 2% rent cap.

Wood says she’d like to see Nova Scotia introduce permanent rent control—which, she argues, would dissuade landlords from using fixed-term leases as a means of circumventing rent caps—and implement a landlord licensing system to ensure the quality of rental units. (Toronto, London, and Hamilton, Ont. have varying licensing policies.)

“It's about how do we go forward from here with that mosaic of solutions, operating in good faith to all involved and create something more liveable for people,” she tells The Coast, “because really, people are not only getting priced out of the HRM; they're getting priced out of Sydney, they're getting priced out of Antigonish. This is not only a city problem, this is provincewide, and it's Canada-wide.”

Province promises ‘more planned’ to combat housing crisis

Change is coming, the province’s housing minister John Lohr tells The Coast—but it’s less clear what form that change will take. The province’s rent cap expires at the end of 2023—and it doesn’t offer any assurances to tenants that they’ll be able to re-sign another agreement after their fixed-term tenancy ends.

Most of Nova Scotia’s efforts, at a glance, appear supply-focused. Lohr points to “a number of projects in the HRM” that the province is working on with CMHC to provide affordable housing units.

He also notes that the province has “created a registry of short-term rentals” and “required all short-term rentals to comply with all municipal regulations.”

“There's more planned in that field coming,” Lohr vows. “We said we’re not finished. We will do more.”