Every October, I get a phone call from my mother. "Are you making that turkey again this year?"

That turkey is a cider-brined turkey, made according to a recipe I found in a magazine about eight years ago. It's a turkey I have made for family and friends, and it has led me to believe that turkey no longer needs be drenched in gravy to be moist.

Before you ask: No, I don't have any knowledge or skill that you or your mother/father/significant other doesn't possess. All you have to do is do a little bit of research, find a recipe and pay attention.

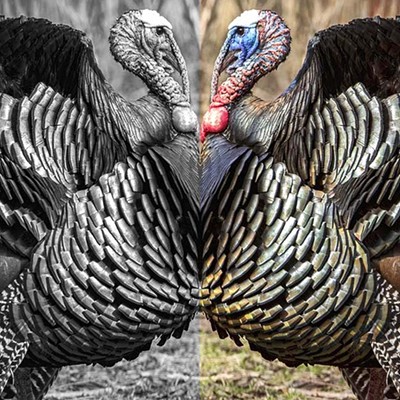

By their very nature and size, turkeys are problematic when cooking. Modern birds have been bred to produce ample breast meat, the part of the bird also known as the crown. This is the nexus of the age-old issue of having overcooked legs and undercooked breast meat, leading people to wonder what is the best way to cook their bird.

Before becoming the academic chair for the tourism and culinary programs at NSCC, Ted Grant cooked in New York for Daniel Boulud, and taught at the Culinary Insititute in Charlottetown. Grant says that when it comes to cooking turkey, he cooks the legs and the crown separately, since their cooking times can vary. He does, however, understand that no everyone is as comfortable butchering a bird as he might be. So Grant suggests brining the bird, placing it in a salt and sugar solution, a process which seasons and plumps up the flesh so that it stays moist and flavourful.

"Brines vary in strength depending on the weight of your bird," says Grant. "You can find a lot of different brines that are fairly accurate online and in cookbooks."

He suggests making an aromatic brine, using the flavours of the season. "Use those fresh herbs left over in your garden. Rosemary, thyme, coriander seed—there are lots of opportunities to play with brines."

But some people relish in the old ways of roasting and basting their bird. Breighan Hunsley went for that route last year when she purchased and roasted her first turkey. Hunsley had spent years as a vegetarian and vegan, eschewing animal products for many reasons. After undergoing surgery for Crohn's disease, there came a change in her diet, but not in her ethics.

"I started eating well-raised animals," she says. Hunsley's boyfriend used to work as a cook at a local restaurant, and he suggested a slow-roast for their first bird, a heritage breed they bought from a local farmer. "I trusted him, because he usually suggests the best way to cook an animal, not necessarily the easiest or quickest," she says.

Heritage birds tend to be leaner than their commercially raised counterparts, with a lower breast-to-legmeat ratio, so they found that this process worked well to suit their needs. It may have been costly in terms of time—the recipe asks for a 13-hour roast at a low temperature—but it promised little-to-no active cooking time and a moist bird.

"The whole process was simple," she says. "I cooked it on Christmas day as the snow fell, and basted it every two to three hours between Christmas specials." It was a big success, and Hunsley is looking forward to cooking another one sooner, rather than later.

But brining, slow-roasting, separating and even using various cooking methods for different cuts won't help you if you aren't paying attention to what you're doing says Grant.

"People are so caught up in the joy of cooking, there is absolutely no way of considering all the variables," he says, noting that not all recipes are made the same, let alone all ovens.

Grant's final advice for a great Thanksgiving turkey: diligence and thoughtfulness. "Just monitor that bird."