Review: Zachari Logan's Topiary at Anna Leonowens Gallery

[

{

"name": "Air - Inline Content - Upper",

"component": "26908817",

"insertPoint": "1/4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - Inline Content - Middle",

"component": "26908818",

"insertPoint": "1/2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - Inline Content - Lower",

"component": "26908819",

"insertPoint": "100",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Zachari Logan, Topiary

Anna Leonowens Gallery, Granville Square, 1891 Granville Street

To September 23

While the word “topiary” may conjure up images of shrubs in the shapes of elephants and swans, Zachari Logan’s latest exhibition by the same name delivers an entirely different articulation of this, but just as luxurious and with just the right amount of camp.

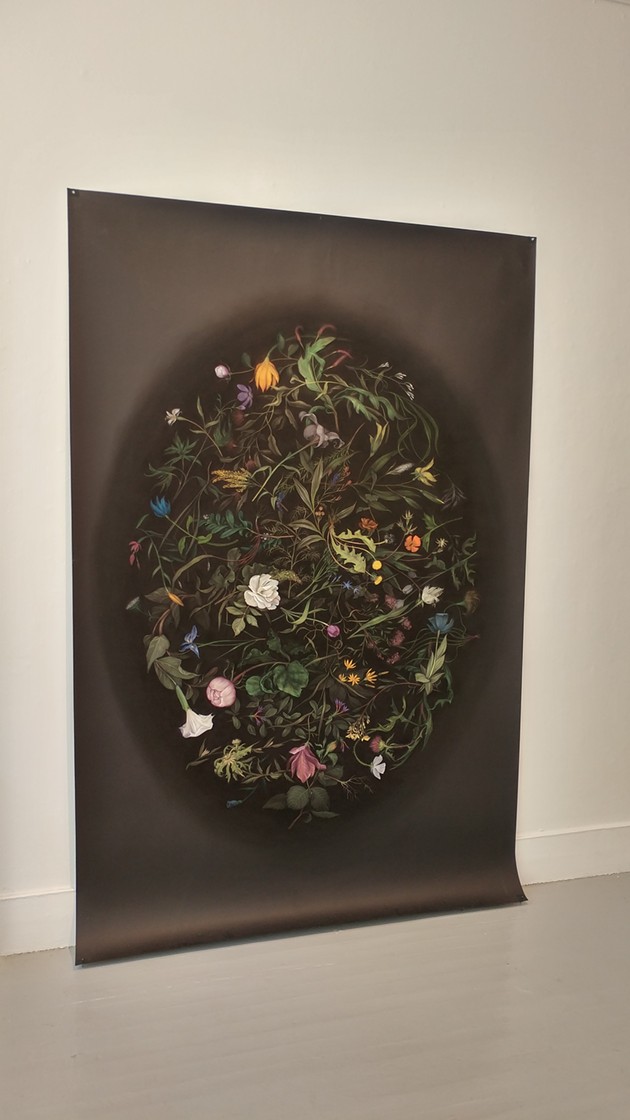

Topiary, now showing at the Anna Leonowens Gallery, is an exhibition of high-realism drawings ranging from large colour pastel botanicals on black paper, to life-size (if not larger) nude self-portraits, and miniature vanitas of human-plant hybrids done in architect’s soft blue pencil.

For Logan, “topiary” refers to “the human manipulation of plants into desired shapes for ornamentation;” an idea he explores in his intricately detailed drawings, with nods historical motifs and art forms, including paper cutting, wreaths, flower painting, wallpaper, and tapestries.

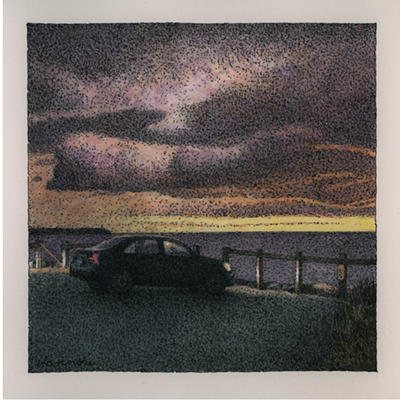

The human figures in these drawings interact with plant life in a way that blurs the line between the self and the landscape. In "Green Man" Logan composes a self-portrait out of plant matter, with green grass growing from his bowed back and halved cabbages forming buttocks, while in the "Eunuch Tapestries" series, male figures become tangled in, partially obscured by, and melt into walls of thick foliage. These plants, like the tall, phallic thistles caressing the naked legs and back of one of the figures, are plants commonly found in the ditches in Saskatchewan, some of the last untouched spaces in the cultivated farm-land of Logan’s home province. Logan identifies queer spaces as ditch-like: liminal and resilient, and through composition he positions the viewer alongside the figure in these ditches.

These Nocturnes (meaning night landscapes) are lit artificially from the bottom of the drawing, as though by car headlights or a flashlight. The result flattens the work, pulls all the detail close to the front, like a medieval tapestry or wallpaper. According to Logan curators and viewers often make a connection to gay cruising in these images–the sometimes semi-nude male figures seeming to hide in the bushes and illuminated by an unnatural light–but Logan says this connection was not intentional. He is, however, quite pleased that that unexpected element is found in these pieces–a queer history at work along with the histories of the decorative arts.

Logan’s use of history is far from stuffy, even though he heavily references some of the most traditional and historically gendered forms of visual and decorative art (both in the masculine and feminine sense): high realism, landscape, self-portraiture, textiles and flower painting. His drawings feel fresh; skillfully and meticulously rendered, rich and luxurious with detail and colour, with even the simple detail of black pastel on black paper creating luminosity.

Part of a generation of artists who value drawing as a medium unto itself (no longer simply a preliminary practice to later works), Logan’s drawings are wedded to their materials–the buttery pastels and tiny notches of graphite feel as tactile as the flowers and flesh that they render.

![Digging in to Max TS Yang’s COVID-inspired art show D[a]UNTING](https://media2.thecoast.ca/thecoast/imager/digging-in-to-max-ts-yangs-covid-inspired-art-show-d-a-unting/u/r-bigsquare/27550319/max_ts_yang_pinned_at_anna_leonowens_the_coast.jpg?cb=1680201675)