Don Connolly's last Information Morning

Friday, January 26, 5:55-8:37am

Cunard Centre, 961 Marginal Road

or hear it on CBC Radio, 90.5FM

Don Connolly still remembers his worst interview of all time: Frank Zappa.

"I'm not a big fan, but I had a significant amount of his vinyl," says Connolly. "He was a notoriously difficult man, and a complex guy, and he didn't like doing interviews." So one day Connolly gets a call from Zappa's record sales rep. He's going to be in town for a concert and he'll be doing two interviews—one with CHUM in Montreal and one with Connolly on CFGO, the Top 40 station where Connolly worked in Ottawa.

Connolly listens in to Zappa on CHUM and he starts to think, maybe this won't be so tough. "He was incredibly accommodating to this [interviewer] and I could tell he knew way less than I did...I played some vinyl and was absolutely ready."

So he drives up in the radio station's "GO-mobile" to the Ottawa Civic Centre, where Zappa is rehearsing. "It was not going well. And he wasn't happy."

After the rehearsal Connolly goes backstage with the tour manager and a guy from the record label, into the hockey dressing room. Zappa's sitting at the table with fries and a club sandwich. He sits down and hits the two little buttons on his Sony TC 110 recorder and asks his first question.

The answer: "No."

Connolly tries another. "No, you're wrong there."

A third question. "No, I don't think so."

"I'm a grown-up at this age," says Connolly to himself. "I'm not some first-year working for CKDU. I'm 27." So he hits the buttons again and stands up. "Thank you very much, Frank—we're done here."

The tables have turned. "Why don't you sit down and have a piece of this sandwich?" Zappa asks. Nope, Connolly says. "We've got everything we need."

"I recognize his contribution. It wouldn't be one of my top 10 bands or even my top 50 but he's a man of tremendous integrity," he says now. "It was just a case of—sometimes it ain't gonna work."

Maybe Connolly was willing to walk away because he lacked the desperation—"thirst," in millennial parlance—of many people aching for a job in broadcast. He says radio has always been a job. A great job, but not the thing that he is obsessed with. That's been his family and friends at home.

"Right now I'm living in the season of cake," he says. Heartfelt notes from listeners saying goodbye. The 90-something woman from Wolfville telling him he's "not allowed to retire" until she dies. It's enough to make you believe you're hot shit, if you hear it for long enough. "Some people, they just want the cake." He says he wants to do the work.

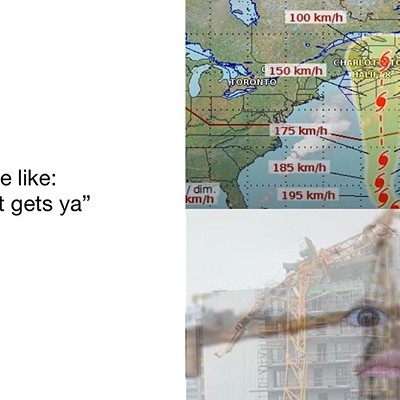

For 42 years, he's been doing that work with the CBC, taking Information Morning and making it something a little different from any other show on air. His voice was a calming presence reporting the news during some of the most turbulent moments in regional history—the Swissair crash, the Westray mine disaster, Hurricane Juan, countless election nights and storm days. The show is based in Halifax, but the team is serious about making something that resonates in New Glasgow and Yarmouth, often hosting remote broadcasts from across Nova Scotia. Working a network of local sources from across the province known as "community contacts"—volunteers in places like Arisaig and Brier Island who came on air to talk about local happenings—they created a province-wide sense of ownership over the show. Connolly says it's cliche, but "somebody in Digby Neck pays the same amount toward the subsistence of the CBC as somebody who lives on Agricola."

When I arrive at the CBC studio at 5:30am, the dulcet tones of Connolly's co-host Louise Renault punctuate the background. She's already on air, hosting her early-morning music show Daybreak. Meanwhile, he scours the internet to print off new stories from sites like The New York Review of Books.

Nearby lay some recently upturned momentos: In getting ready to pack up and leave, he's gone through his bottom drawer. A pair of castanets are out. An old compilation of historic Don moments is yellowing. He shows me and CBC publicist Greg Guy the dregs of a bottle of orange brandy he found in his desk when he first arrived at CBC's former building on Mill Road. "Just in case there's a real emergency," he jokes.

We head into the studio, where Connolly and Renault will start the show. Their banter is fun and familiar; today, they'll talk about a Clipper—"a Western storm named after a ship," Renault says—coming Halifax's way.

But before they go on air, Connolly confers with her about a new script he got. There's a pun in his introduction, for a story about fishers raising money for the families of children who died in West Pubnico. "I don't think so," he says, his voice low. She agrees. The changes are made, and the show keeps chugging.

Barring these kinds of editorial discussions, Connolly's implicit promise to his producers over the years was that he'd read the background you laid out and your first question. Aside from that, he was a wild card—a free-flowing, conversational interviewer. By the end, you'd know what you needed to, but it felt less stilted–like an actual conversation.

Connolly says he's heard from people all over the province who say they started listening to the radio in the mornings after their husband died, their kids moved out, they were suddenly alone in the house. Just as much as the information, he says, he believes people are tuning in "for the company."

"Anybody who's a longtime listener knows his dog is named Oreo, his wife's named Maureen, and his daughters refer to him as 'the kitchen bitch,'" says Jerry West, an associate producer on Information Morning. It's not uncommon for someone in the north end to hear their dad tell them they live near Don Connolly's house—as if the two somehow know each other. On air, Connolly's fond of saying that he's the least important member of his family. (Oreo, obviously, comes first in the long list.)

Kathleen Connolly, his eldest, isn't totally sold on that. "I actually do believe him, in his heart, that that is how he feels—that is the environment he tries to foster," she says. "The dog is the most important sentient being in the house and it goes down from there. But there are some things that are unquestionably his. Like the spot on the couch. And the remote control." However accurately it was constructed, for fans, that sense of familiarity was heady stuff. When Connolly announced in November that after 40 years at Information Morning he would be retiring, Anne Bauld felt compelled to send him a gift. She bought a hand-crocheted antimacassar of his name from a local artisan in Pubnico, popped it in a little gift bag and sent it to the station."He's just part of my day," says Bauld, 74. For her, Information Morning is a ritual. "He has a very calming voice and I like the reassurance that he's there. His compassion comes across."

For new producers, however, Connolly's style could be frustrating at first. West says there was a chunk of time where he just gave up on kicking his own ass scripting good questions, because why bother if Don wouldn't read them anyway? But then he started to see how this particular host worked—having a conversation, running out of steam and then looking down at the sheet and picking the right moment from the pile. It's more of a tool. "I can think of two or three times in the past nine years where he read all the questions I had written on the page," he says. "One of the things it's done for me is it's, as often as not, he pulls something out of the interview I didn't know was there."

"Anybody who's a longtime listener knows his dog is named Oreo, his wife's named Maureen, and his daughters refer to him as 'the kitchen bitch.'"

tweet this

His approach was working: Information Morning has been the highest-rated morning show in Nova Scotia (and Best of Halifax morning-show winner) for years. In 2017, it hit a record-high market share of over 31 percent. Which means that as Connolly steps away from the chair, the show's producers, newscasters, technicians and co-hosts will have to figure out how much of that success they can recreate without him.

"I feel for whomever comes in after him," says Renault. (She didn't apply—she comes from a film background, and wasn't interested in the journalistic burden.) "But also, Nova Scotians are generous, and I hope they will trust that we are going to take care of this show. This success—definitely, Don's a big part of it, but we also have an amazing team and great reporters."

Nonetheless, says morning news editor Sandy Smith, "It is kind of scary. It'll be a real litmus test because we'll see how much is the whole CBC brand, and how much is Don."

Connolly sneaks out of the host chair for a cigarette. "It's gonna be a quick one," he says. A Player's in hand, two drags and he's already throwing it back onto the pavement and turning for the door. He might have been able to smoke more if he walked back to his seat a bit faster. But in interviews and in life, this is a guy who chooses his own pace.

Born in Antigonish and raised in Bathurst, NB, he was named after his uncle Don, an air force pilot who died in WWII six years before he was born.

Raised Catholic in this tight-knit town, which "meant that you were a Liberal and you cheered for the Montreal Canadiens," and an altar boy right up until Grade 12, Connolly went to college with self-imposed plans to go on to law school, marry and return to run his father's contracting business.

But then the 1960s happened.

By the time he graduated from St. Francis Xavier, it was the height of anti-war hippie fervour. "Anybody in Nova Scotia who tells you they were rolling one up or smoked a joint before 1968 is almost certainly lying to you—because it wasn't here," he says. "The '60s kind of arrived in Nova Scotia in 1969. I was finishing up at St. FX. No longer an altar boy. Got rid of all that kind of stuff. And I realized I could still be a good person and...not run Connolly Construction. So I end up, I finish at St. FX at 1969—and I have no idea what I want to do."

He spent a year working in a mine—"unreservedly the worst year of my life," he says. He tried graduate school at Dalhousie—"it would have ruined books for me! I'm a book guy." Finally, in an attempt to pay off his student debt, he took a job at a new weekly paper in his hometown, The Bathurst Tribune. This one stuck (until he got laid off). He got a series of radio jobs—Zappa interview included—until he got the choice between overnights at CHUM-FM in Toronto or co-hosting Information Morning in Halifax.

This was a couple decades before the decline of commercial stations across the country, so CHUM would have been the smart career move at the time. But Halifax was where his friends were. So Connolly rolled in with a hippie mop of hair to CBC, co-hosting with Don Tremaine, a military veteran about 30 years his senior, for 11 years before he was handed the torch.

For Kathleen—who "didn't listen to him a lot growing up if I'm being totally honest"—the fact that he had a full-time career as a radio host was incidental to what she saw as his real job— cleaning up after her and her three siblings and making them food. "We didn't know, or think, or acknowledge, that he had a full-time job in addition to the things he did," she said.

When I show up at Connolly's north end home on a Saturday, he's inthe back of the house, "kitchen-bitchin'"—making a potato-and-cheese frittata.

News is playing on the TV in the living room nearby. Connolly starts rifling through his kitchen cabinet to pick out a cast-iron pan that's stood the test of time. "It's hardly an exaggeration to say I could hardly boil an egg as an adult and when I moved back here in the first couple of years my friend Robert McKelvie—he died this summer, of the McKelvie's restaurants downtown—came to my door, fourth floor of the Elmwood, opened my door with this very frying pan, and said 'Learn to fucking feed yourself.'"

He didn't. "I kept thinking, how the hell are you surviving," says Maureen.

That changed over the years as they had kids. Connolly would wake up at 4:45am, get dressed downstairs so as not to disturb Maureen, and get a cab to the station. Maureen would take the kids to school before heading to work herself. He would return around 1pm before taking a nap and reading, so when the kids came home, food became his thing. "It was dictated by the realities of our family.

"Somebody's gotta do it—and it turned out to be me...I'm only just adequate at it," he says.

Kathleen saw her mom pursue several career goals, including an MBA, while her dad took on this traditionally feminized labour. She says this upbringing made her a feminist.

"He didn't realize all the ways in which he was imparting that kind of stuff, but he was," she says. "There has never been a single moment when I felt like there was anything in his mind that was more important than the family was."

When I badger him about his retirement plans, Connolly suggests an academic exercise. If we pull out the first page of Maureen's Herald and flip to the first-page obituaries, he's willing to bet that more people on it will be younger than him than older, he says. Retiring at 70 is a little different from Freedom 55.

"I finished high school in Bathurst in 1965. Kathleen was born in 1985," he says. "Those 20 years, every minute I had—every dollar I had—was mine. I've had a 20-year retirement when I was young and strong. So that's kind of not the thing."

I push. He has 40 hours in a week currently booked by work that are going to be free of any itinerary. Surely he has something he wants to do with that time?

Well. He'll be reading books. Tough ones. The ones that require "heavier lifting." He's got Don Quixote on his list, even though he's afraid it'll make him sound like a douchebag. He'll be going to Italy and Ireland with Maureen. And he wants to hit up his old "party liners"—community contacts—in places like Pubnico to visit the province and do some road trips. To do that, he'll have to get his own "shit-kicker" of a car—and get his driver's license again. He quit driving (in an effort to walk more) in his late 20s.

Meanwhile, Information Morning still has a show to put on. CBC is interviewing for its next host this week. Smith hopes the new host will "maintain Don's tone," while Renault would like to see whomever is chosen bring something new to the show: "This is an opportunity to shuffle the deck."

What Renault doesn't want to see: A diet Don substitute that leaves people craving the original. "You couldn't have another Don Connolly-ish," she says. "You can't fill Don's shoes. It has to be someone who's very different—but with some strong sensibilities about being curious about things and curious about this province."

As for listeners like Bauld? "Well, I will certainly miss him and I feel sad that he's going, but I know it can't go on forever," she says. "I'm a big CBC Radio fan.

"I'll still be listening."

Katie Toth is a Halifax journalist.