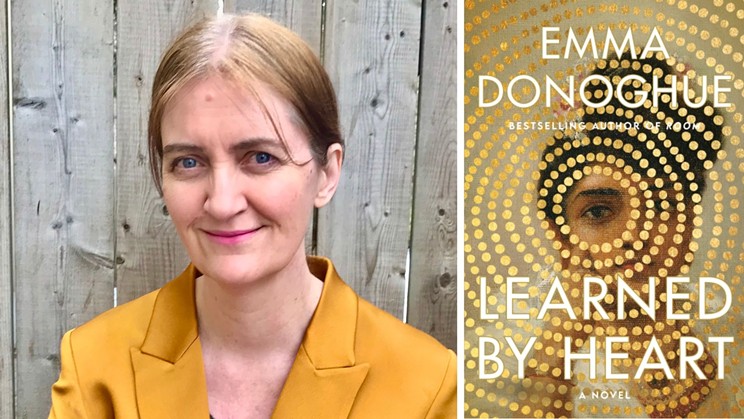

Emma Donoghue isn’t finished writing. Even now—15 novels, a dozen-odd plays, five short story collections, three screenplays, a Booker Prize shortlist and one Academy Award nomination under her belt—the Dublin-born, London, Ont.-based author can’t quell the storm of ideas that nag in the corners of her mind for a glimpse of a page, a chapter, a first draft, a finished story. Every subject has potential. The 54-year-old has delved into the lives of seventh-century monks (Haven), kidnappees (Room), cross-dressing frog catchers (Frog Music), even hospital workers during the 1918 flu epidemic (The Pull of the Stars).

Donoghue’s latest novel, Learned By Heart, hearkens back to a recurring theme of her work: Queerness. In it, the Irish-Canadian author—herself a lesbian—imagines the early life of gay pioneer Anne Lister, dubbed Britain’s “first modern lesbian.” At 14, Lister fell in love with orphaned heiress Eliza Raine. The two met at boarding school. But, Britain of the early 1800s being what it was, the budding romance grew amid a backdrop of intolerance and strict social codes.

“It provides a lovely contrast for a story of falling in love, because love is so uncontrollable and spontaneous and wild,” Donoghue tells The Coast.

Donoghue will visit Halifax on Sunday, Nov. 5 for the AfterWords Literary Festival. She’ll be speaking at a morning brunch event with Nova Scotia author Charlene Carr and an evening conversation with longtime journalist Sarah Hampson.

Ahead of Donoghue’s arrival in Halifax, The Coast spoke with her about her latest novel, writing about queer love in a time when queerness is under threat, the “empathy machine” quality of books and life after Room.

This conversation has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

The Coast: How and when did you first come across the story of Anne Lister?

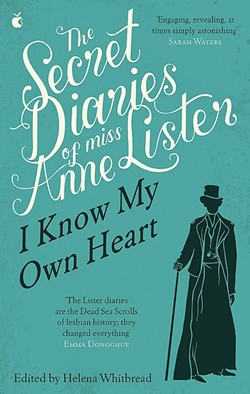

Emma Donoghue: It was a rainstorm in 1990. I ducked into a bookshop [in Cambridge]. The first book of excerpts of her diaries had just been published by Virago, and my eye landed on that classic green cover. Hers was a voice I’d never encountered before: Early 19th century, really erudite; interested in everything scientific, but also attuned to all the little social subtleties. And this diary spoke frankly about her relationships with women—and in a way that was unlike any other source I’d come across.

Really, I’ve been preoccupied with Anne Lister for 33 years now—it’s ridiculous [laughs]. I wrote my first play, I Know My Own Heart, based on those diaries of hers from her 20s, and I wrote Learned By Heart to kind of answer the question for myself of what she could possibly have read that allowed her to have this sense of not just desiring women, but also her gender nonconformity. She was fascinated by her own identity in a way that strikes us now as so modern, right?

Is it true that she wrote parts of her diaries in code?

Yeah! Fifteen percent of her diary is in a code that she invented based on numbers and Greek letters. And she used the code for anything she wanted to be a little private about—like, you know, money matters; her family was often in debt. And also, clothes—she was a bit shy about matters of clothing, as well as her relationships with women. So because of that, it’s never been published in full—it should have been a multi-volume edition from a university press decades ago.

But now, fans of the TV show Gentleman Jack [which portrays Anne’s life] have gotten in on the action. Hundreds and hundreds of fans have signed up as codebreakers and transcribed the pages one by one—so it’s an amazing kind of alliance between librarians and writers and researchers and fandom.

In Anne, you have a nonconformist—but the setting of the novel is very much a world of conformity: English boarding school. Students are disciplined for anything from wearing the wrong clothes to speaking out of turn. What was it about that world that sparked your interest in setting a novel in it?

I suppose the main reason I chose to write about this part of her illustrious life is that it’s before the diaries. I wouldn’t want to write a novel that was really just rewriting what she already said. I like the mysterious quality, that this is a key year in her life when she fell in love at 14, and we don’t have her account of it. And also, who she fell in love with—she falls in love with this biracial heiress from India, Eliza Raine, who, in some ways, has all this status. She’s beautiful, she’s rich, she’s got £4,000 in the bank—which no Jane Austen heroine ever had. But also, she’s basically the one brown face in town.

So I was very interested in those two outsiders falling in love in the first place. But as you point out, the boarding school setting is really crucial as well, because it’s a microcosm. Already, Regency society was a world of elaborate rules that strike us as ridiculous. For instance, when Eliza Raine was in her 20s, she went to Bristol one winter and couldn’t make friends with anyone, because she didn’t have one acquaintance who would introduce her. Given the absurd social structures of the time, a boarding school is a wonderful kind of miniature, absurd version of that—because in boarding school, the rules are so petty: If you took three slices of bread at lunchtime, you were only allowed one at dinnertime.

It provides a lovely contrast for a story of falling in love, because love is so uncontrollable and spontaneous and wild.

What were the attitudes toward queerness like in early 19th century England?

It was so different for men and women. Men’s sexuality was seen as the real thing; it was dangerous and had consequences. The terror of men leaving their fortunes to illegitimate babies meant that there were all these rules, basically, to keep women loyal to their husbands. The emphasis was on heterosexual sex, and gay sex was was penalized—they could be executed for it.

By contrast, lesbian sex was really below the radar. So where boys’ schools would have all these rules about, like, no sharing beds, or no boys are to be alone in a room together, in girls’ schools, the focus was not on that at all. In a way, a relationship like Anne and Eliza could get away [without scrutiny] to a point, because what girls did together was seen as unimportant; like, there was no penis, and therefore, nothing was really happening. I’m not saying it was allowed, but if you were fairly discreet about it, it was invisible.

It’s an interesting time to write about, because I think Anne and Eliza would have felt astonishingly isolated. Like, no one in the world has ever felt like this. But equally, they would have loved the sort of privacy of their relationship not being visible. Of course, Eliza had the hypervisibility of being biracial. One thing that comes up a lot in the novel is whether it’s a good or bad thing to be different or special, because Anne Lister is very much ahead of her time, and basically proud of what she called her own oddity. But Eliza is often saying, like, “I don’t want to be pointed out, or considered exotic or a freak.”

I have to say, I drew on a lot of autobiographical material, because realizing I was gay in 1980s Catholic Ireland, the feeling was not that different. I had this feeling of, “I’m the only one in the world.” I didn’t know that someday I would move to Canada to be like everybody else.

Your book The Pull of the Stars, set during the Spanish Flu, came out as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the globe. Now, Learned By Heart arrives at another timely moment: Around Canada—and even in Halifax—we’re seeing a moral panic around the presence of queerness, and especially gender nonconformity, in schools. This isn’t the first novel of yours to centre queerness—it’s there in Stir Fry, and Hood, and The Sealed Letter and Slammerkin—but did any part of it feel more urgent this time? Or was it sheer happenstance that as you’re writing this, these sorts of issues are bubbling up?

It’s a good question. Who would have anticipated that we’d have governments fighting with each other over pronouns? I shouldn’t laugh, but it’s painful. I mean, we’ve had big, fierce demonstrations and counter demonstrations here in London, Ont., for instance, about the very issue of pronouns. And it wasn’t my motive for writing the book, because I’ve been planning this book for so long—but certainly, as I was writing it, I was acutely aware that these issues felt more contested than they were 10 years ago, even. And I was also very aware that Anne Lester has been seen by many trans and nonbinary people as kind of a forebear of theirs, as well as a forebear to lesbians.

“Who would have anticipated that we’d have governments fighting with each other over pronouns?”

tweet this

We can’t map the lives of the past neatly onto our own. I think she has a lot to offer readers of all stripes. You know, in Anne’s diary, she says things like, “I might be the connecting link between the two sexes.” She never says, “I want to be a man,” but she really does explore her position on that kind of line between genders. So I tried to write her very much in a way that was welcomed into that interpretation as well. And that for her, expressing her particular ambiguous sense of gender was just as important as the fact that she desired women.

So yeah, it did come to seem weirdly urgent as I was writing it—and even just to write a story about two girls falling in love. Ten years ago, that would have felt fairly noncontroversial, but in the context of book banning in America in particular, to write about really young people who are certain of what they feel, it did feel crucial.

I’m interested in your perspective on being a writer in times like these. We’ve been living through what feels like some of the hardest financial times in years. And when money’s tight, it often seems like the arts are one of the first things that fall under the public fund chopping block, or they’re dismissed as a frivolity. How do you navigate your place as a writer in a time like this? Does it feel as vital as ever?

It really does. In fact, during COVID, it felt even more vital—because suddenly, a lot of people weren’t able to do the jobs they were used to doing. Good books and TV got them through. It may have been a big blow to cinema—and it was an awful blow to theatre; I mean, the play of my novel Room was cancelled on opening night due to COVID. It took us two years to mount it again.

But people were just watching TV and reading books compulsively. I’ve met bookstore owners who say that COVID [kept their store alive]. I found it very moving that people resorted so much to narratives to not just pass the time, but to entertain and make meaning for them. And I don’t know. It probably didn’t particularly change my sense of how much the arts mattered; it’s always seemed to me that they mattered.

I’ve always had a really strong sense of vocation about being a writer: I know this is what I’m meant to be doing with my time. And in particular, when I meet readers and talk to them, and when they’ve connected so strongly with my books, I’m just convinced this is how I should be spending my life. I think books can make such a difference to readers. I mean, they can change minds. They can enlighten you and open your mind and your heart; they’re empathy machines. So yeah, books feel more crucial than ever.

Has your idea of writing changed throughout your career from when you wrote Stir Fry in 1994?

It’s much the same. My life has had a weird continuity [laughs]. I’ve been with Chris for almost 30 years, so a lot of my life has been the same for 30 years. And that’s fantastic; I wouldn’t want to mess with it. And it’s been great that we’ve had kids, because kids introduce such a sense of change and history. You know, you remember things so vividly from all that was before the kids. And then, “Oh, that’s when the kids were babies.” So that has provided a lovely sense of each year being different from the next.

I was just really, really lucky to hit on the right career so early, and I’ve just clung to it. The nice thing, too, is that writing has a lot of variety built into it—especially if you embrace other genres. Adapting my work for the stage and the screen has been such a pleasurable change, because it’s so collaborative. And writing for children was a brand-new challenge. Recently, I’ve been collaborating with a composer on a musical. It’s a great way to keep you on your toes.

Speaking of change, you were a mid-career writer by the time your book Room became an international bestseller. It became a Hollywood movie; the adapted screenplay earned you an Academy Award nomination. What is the before and after of Room like in your life?

I think it made a big difference to other people; they suddenly saw me as a big shot. Whereas to me, my relationship to my writing was exactly the same. It’s great knowing that more people will tend to take a chance on my books if they recognize my name—in a way, it gives me even more freedom, because I can write about a book about whatever I like and trust that some people out there will go, “Let’s have a look at this one.” Like with my last novel, Haven, quite a few readers have said to me, “I never thought I wanted to read a book about monks on a medieval island, but I tried it out.” So that's been great [laughs]. But that all comes after the fact.

I mean, the fundamentals—me, my laptop, making up stories—that has felt exactly the same since I was 20. And I’m now 54. So I’m really glad that my big hit was in mid-career, because I think if it’d happened with my first book, I’d have a totally artificial sense of the world. You’re like, “Bringing on the champagne!” every time you publish a book [laughs]. Whereas I know publishing a good book is usually a very quiet business. This is just my trade. I do this as if I’m making furniture: Some of the products will be far more successful in worldly terms than others, but that doesn’t alter my fundamental pact with my writing.

How do you feel that life in London, Ont. has influenced that perspective?

Well, it’s by no measure a cool city, okay? But I have to say, because my life has included so much travel away from home, having home be a relatively quiet place is great. I mean it’s not the back of beyond—there are always films to go see, and sometimes plays, and there are people. I would never live in a small town, but as a base for life that includes a lot of dashing off to England and Ireland and America, London has been just great.

Do you still write from a treadmill desk?

It’s part of my day. It’s not all day, because I’ve had some back troubles. But because I want to live forever, obviously, and I have so many books in my mind that I need to write, I have to keep myself alive—and the writing life is not a particularly healthy one.

Really, I don’t care where I am. I’ve been working on my book tour. I’ve worked on trains and planes and automobiles—not while driving, obviously, but I’ve worked in parked cars or in the backseat of cars. I’m very relaxed about where I work. Really, the laptop is just a kind of portal into my writing world.

What’s the last book you read that stuck with you?

I just read Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain a few days ago. It’s a very analytical history of the Sackler family and the opioid crisis. And I would say that one has given me a very definite and furious sense of how we are peddled, you know, the whole range of pharmaceuticals, basically—and how much goes into persuading us to take these things. It’s certainly lodged in my mind.

What would you be doing if you weren’t a writer? I know you’ve mentioned a failed venture as a chambermaid many years ago.

We’re not going back to that one [laughs]. I really doubt my skills have improved since I was 18. It’s not that I would completely lack the other skills; I’m sure my qualities of, you know, vision and organization and human interaction could work in another job, but I wouldn’t know who I was. I can’t picture myself in any other life, or I can only imagine myself deeply unhappy, you know? No, I’m afraid this is it.