When Nova Scotia announced it would be enacting a state of emergency—giving police officers new powers to enforce social distancing rules—the first thing Kate Macdonald did was try to learn as much as she could, as fast as she could, about the new rules.

“How does community keep community safe in these times? Because it's not the police ever,” says Macdonald, “and it's extra not the police now. And now the police have these direct government directives to be rogue.

“It's a bit of a free for all, which makes me obviously very nervous and like we can already see the pattern of how this is going to go down.”

As a Black person living in Halifax, knowing the ins and outs of the law is her best defence against a police force that up until last year was street checking Black Haligonians at a rate six times higher than their proportion of the population would suggest.

“I rely on knowing the law,” says Macdonald, “so that when push comes to shove I can recite the law. And we know that that still doesn't always work.”

COVID-19 and the resulting state of emergency has left the law in the hands of our top doctor’s favourite phrase: common sense—a flimsy and subjective notion that favours the privileged among us.

The shift has left Macdonald and other Black and racialized Haligonians with heightened fear, wondering what happened to three years’ worth of well-meaning talk about improving police-community relations.

Madconald works in Halifax as a youth representative and community stakeholder. She and Trayvone Clayton, a criminology student at SMU, have been on the front lines of that talk, working in their community with Halifax’s leaders, the police and the province, speaking out and organizing on behalf of their community in the name of fair and better treatment from police.

As youth, they’re picking up the torch from their elders and those who came before them—those who have been speaking up about mistreatment from police “for more than 20 years,” says Clayton.

Three years ago CBC reported on street check data, finding that Black people were 3.1 times more likely to be stopped in a street check than white people in Halifax. Then a two-year Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission study was published in March 2019, which confirmed and expanded on that reporting.

The report outlined two avenues for going forward: either ban street checks, or heavily regulate them. The province announced a moratorium (a temporary ban) on street checks in April 2019 while it was “working towards strict regulation.” Members of Halifax’s Black and African Nova Scotian community were calling for a ban.

The Wortley Street Check Action Working Group was set up and Macdonald and Clayton were invited to take part, but Clayton, Macdonald and other Black youth left the working group after just three meetings—the plan to regulate "counteracted with our beliefs and the communities' beliefs in relation to street checks.”

After a second report from the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission confirmed that street checks were illegal, Nova Scotia changed its mind on regulation and announced an official ban on street checks in October of 2019.

When the ban was announced, Clayton told The Coast: "It feels good to know that we will no longer be...stopped due to our skin colour."

"Being able to walk through a neighbourhood, and walk through a community...it is good. We don't have to have that feeling no more that we're gonna be stopped for no reason.”

Now, the provincial state of emergency—which allows police officers to stop anyone who is deemed to be breaking social-distancing protocol—could halt what little progress had been made.

The provincial Human Rights Commission selected University of Toronto criminology professor Scot Wortley to do the review of police street check data and experiences in Nova Scotia. The resulting 186-page report laid bare the fact that Black people in Halifax were disproportionately targeted by police using street checks.

The report also laid out community recommendations that came from Wortley’s research speaking with police officers and members of the African Nova Scotian community.

One was to “Improve Police Communication Skills: Participants often argued that it was the nature of police treatment, not just the frequency of police contact, that eroded trust in police services. It was expressed that officers need to learn how to better communicate with or talk to the people they interact with in public. They need to treat people with respect. Several participants also expressed that the police need to do a better job explaining their actions–including why they conducted a stop and why they are asking particular questions.”

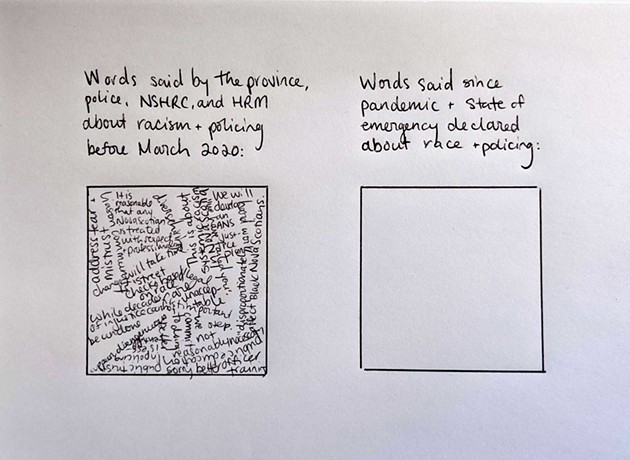

COVID-19 has provided lots of chances for officials to practise their communication skills, and reassure people that past mistakes won’t be repeated, even as the state of emergency gives police sweeping authority.

But when asked at a press conference by CBC reporter Shaina Luck what commitment he would make to ensure the wide power to ticket and even arrest people doesn’t "disproportionately affect people who are Black, Indigenous, homeless, mentally ill, new immigrants, otherwise marginalized,” premier Stephen McNeil answered that the virus doesn’t discriminate. “The virus is after all of us,” he said.

When asked by The Coast how the new powers granted by the state of emergency differ from a street check, Jodi Sibley, communications advisor with the department of justice, said “Street checks are banned in Nova Scotia and that will not change while a state of emergency is in effect.”

The statement continued: “Police are required to enforce rules related to self-isolation and social distancing as set out in a public health order from the Chief Medical Officer following the declaration of a state of emergency across the province on March 22, 2020. In carrying out this role, police and law enforcement officials can request identifying information from citizens, when required, for example, when issuing a summary offence ticket under the Health Protection Act or the Emergency Management Act.”

It finished with: "We have communicated with our law enforcement community and understand the approach they are using continues to be one of education and awareness, and enforcement as necessary.”

When asked by The Coast if there was a plan to ensure changing directives are sufficiently communicated to those "with little access to internet, those living in shelters with no phone, those who due to historical over-representation in policing have a mistrust of police services,” Halifax Regional Police’s public information officer John MacLeod said, “Our overall approach continues to be to use a combination of education and enforcement as necessary. We know that most citizens are doing what they should to protect themselves and others from the COVID-19 virus, and we encourage them to continue doing so. With the enactment of the state of emergency for Nova Scotia, it is important that people are closely following the direction and educating themselves on the expectations in the interest of public health and safety.”

Three opportunities to acknowledge that Black people are disproportionately targeted by police in this province, and three blanket statements that do nothing to communicate to these communities that the state of emergency won’t harm them at a rate their experience tells them it will.

It’s unfortunate, says Macdonald, “because we were, I think, in a good position. Not good—you’re never really in a good position with the police—but we were in a position to be having conversations with Dan Kinsella” (who officially became chief of Halifax Regional Police in summer 2019) “and some other folks involved in HRP and some other community members. So it's unfortunate that all of this is unfolding in this way, because there is this disconnect in communication.”

The long back and forth on street checks was slated to come to some sort of conclusion—a “historic” day—when the Board of Police Commissioners-recommended apology for the racism experienced with street checks came from Kinsella at the end of November. But Clayton says it felt like a bandaid.

“The police, the first thing they did after the apology was brutally beat a man up on Quinpool Road. And then they got the young lady at Walmart. And then after the young lady at Walmart they got a 15-year-old out in Bedford. So it's just like, I thought the apology was supposed to put us 10 steps forward. But now it's just like the apology put us 20 steps back. It's even worse than the street checks, now we're getting brutally beaten.”

“The police are allowed to just chuck a $1,000 ticket at someone,” says Clayton, for, up until last week, walking through a park, or now, being on the wrong side of what common sense looks like to a police officer sizing up your social distancing in public.

And if the Halifax Common—open, closed, no thoroughfare, some thoroughfare, dinky little flags lining some paths but not others, open again—can be an example, sweeping measures to slow the spread of coronavirus have been communicated in a lopsided way.

“We're still in this kind of like mid-ground purgatory where the law is nebulous, and human rights are in question,” says Macdonald.

Not knowing what basic human rights she has during the state of emergency is “a very scary thing to think about.”

Clayton knows a police officer who gives him a heads up about changes, and has shared how things have been unfolding in the US around the coronavirus, but like the rest of us he’s been following updates on the internet. He says there’s been no specific communication between his community and the police: “It’s just like, I think they kind of like this and they want this, they feel like this is their job now so it's just like we can't question it because this is what they were told to do.”

When the law—or perception of the law—is nebulous, Macdonald says all the lessons she and Clayton have taught to the many youth they mentor are “effectively void.”

The province’s long list of dos and don’ts around parks reopening leaves lots of room for interpretation: trails and parks are open but don’t drive to them but you can drive if you have to drive but if the parking lot is too full you should drive somewhere else but you shouldn’t drive but it’s OK if you do.

Just “use common sense” said Nova Scotia’s chief medical officer of health, Robert Strang, repeatedly, when outlining the changes.

When common sense is the rule but also inherently subjective, Macdonald has nothing for the Black youth she’s supporting to fall back on if they find themselves the wrong kind of six-feet away from someone else.

“You can't like say the right thing, you can't hold a law up in your favour. You can't be in the right place at the right time. You can’t hang with, with anybody basically, and that reality of the fear of going outside, it's just amplified by like a thousand.

“I think that it's a very delicate time to be Black,” Macdonald says. (It’s always a delicate time to be Black, she adds.) “You're always very aware of your...privilege to be alive.”

Halifax’s hands-off police oversight body, the Board of Police Commissioners, has been put on hold since COVID-19 ended in-person meetings. In mid-April, mayor Mike Savage told The Coast it was a priority to get the Board of Police Commissioners meetings running virtually, but they still have not resumed and there’s no word on when they’ll be back. But “the work continues," says Natalie Borden, chair of the police board, in an email.

"We continue to plan for future meetings, and I have regular check-ins with RCMP and HRP chiefs to get updates and identify any significant risks, and information is being shared with the commissioners. RCMP and HRP are working hard and responding quickly to ensure service is maintained, and that they can adapt operations during this state of emergency."

Even without the oversight and accountability of open meetings, Borden said “I am confident that they are making the necessary changes required to ensure the safety of their employees and the public, while maintaining public safety.”

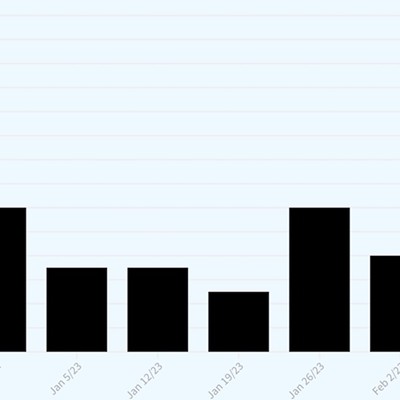

Less confident in law enforcement’s ability to ensure and maintain public safety, researchers Alex Luscombe and Alexander McClelland in Ontario have been tracking post-COVID-19 police actions across the country in their project Policing the Pandemic. They reported this week that $5.8 million in fines have been handed out to date in Canada—across over 4,500 tickets or charges.

Halifax Regional Police handed out 159 of those tickets—seven tickets were handed out over the weekend—and Nova Scotia RCMP has handed out 190. (Based on these numbers, Nova Scotia has a higher rate of ticketing per person than the national average.)

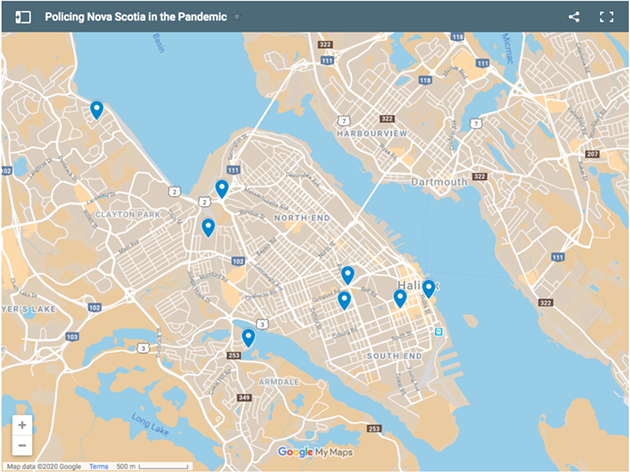

Here in Halifax, El Jones, Rebecca Faria from Hollaback and the rest of the Black Power Hour team have developed Covid Cops 902, an online tool to track interactions with police, as well as broader police and neighbourhood surveillance during the pandemic.

“The idea of public safety, who that has included and doesn't include, has never included Black people, queer people, sex workers, people without homes,” says Jones. "So we know that it opens up this huge room for the groups that are already targeted to be targeted without the ability for us to really protest it, to know what's happening, to speak together cause we can't go out.”

Jones says Covid Cops 902 is a way to get a picture of how those groups that are already outside this idea of the “public” are actually being treated under these new “public safety” measures.

When Strang first announced the state of emergency and explained it would be enforced by huge fines from law enforcement, he did ask Nova Scotians to pause before narcing on their neighbours.

"Maybe there's something they're struggling with that they need help with, that's forcing them to come out of self-isolation," said Strang. “So rather than be negative about each other, I'm encouraging people as a first step is let's figure out how we support each other.”

But more than 1,500 calls have come in to Halifax Regional Police from residents about people not following social distancing protocol anyway.

So far nine incidents have been recorded in HRM on Covid Cops 902, from citizens submitting their own complaints they called in, to people who observed police approaching panhandlers and a white neighbour who called the police to report a 14-year-old Black youth playing basketball alone at Rockingham Elementary School.

“It’s interesting,” says Macdonald, “because instead of turning towards empathy, now we're turning towards blame.”

After claiming that coronavirus doesn’t discriminate, premier McNeil gave fuel to old stereotypes when he singled out a few COVID “hotspots” including East and North Preston in April. “The reckless and selfish few in some of these communities are still having parties,” the premier said. “For the love of god, stay home and stop partying, please, for the sake of our province.”

It was language that “exacerbated long standing anti-Black racial tensions in the province, and stigmatized members of these communities as vectors and carriers of disease,” reads the open letter demanding an apology that followed. “The history of medical racism in Canada, along with the importance of the social determinants of health cannot be set aside during this pandemic.”

Macdonald says that feeling of fragility—compounded by COVID-19—contributes to the paradox she sees unfolding in front of her, where privileged people are learning what that fragility feels like for the first time.

Watching the rest of the world get “a taste of what it is like to be over-policed…to be constantly watched, to be constantly scrutinized, to not have access to all the things that you want whenever you want them, and everyone can’t handle it.

“People are just so shocked that the police are gonna show up in this way,” says Macdonald. Shocked that they can get fines for standing too close to their friends, shocked there are so many cop cars in the neighbourhood and that they can’t be outside living their life however they want, whoever they want, wherever they want. “It's like, that's genuinely being Black.”

Clayton was on the phone with a friend of his, who was describing seeing caution tape everywhere. “I don’t think some people in south end have ever seen caution tape before, the way they're going on right now, and this is what they do in the Black community every single day," says Clayton. "This is what we see every single day.”

“The hyper-vigilance that privileged folks are starting to feel…this need to constantly be looking over your shoulder and wondering am I doing the right thing? Am I gonna get in trouble? That is a pre-pandemic walk outside” for Black people, Macdonald says.

Clayton quips: “Welcome to the real world.”