On your way up the staircase towards the journalism school, on the third floor at the University of King’s College, you pass a poster on the wall that’s larger than you. There are more of these across campus, but this one focuses on what's through the doors at the top of the stairs. It’s Call 86 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 94 Calls to Action, published in 2015.

It reads, “We call upon Canadian journalism programs and media schools to require education for all students on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal-Crown relations.” Call 86 is one of three calls specific to media and reconciliation.

Trina Roache teaches “Indigenous Peoples and Media,” a new mandatory second-year course at King’s’ journalism school that was added this winter. With the addition of this new mandatory course, King’s has fulfilled its promise towards Call 86.

Roache is an assistant professor at the School of Journalism at the University of King’s College, and a member of the Glooscap First Nation. Roache designed the course as a response to the call, centering on the Mi’kmaq–the Indigenous Peoples who have lived in what is now called Nova Scotia for more than 11,000 years.

The non-profit group Indigenous Watchdog tracks the progress of all 94 calls and will be publishing the results of Canada’s journalism schools response to Call 86 at the end of March.

There are roughly 30 students in Roache’s second-year class. They meet once a week on Friday morning. It’s a small class, where students think about what decolonizing journalism means and looks like, as well as how journalism maintains the status quo and perpetuates mistrust between Indigenous Peoples and the media when journalists get it wrong.

In one assignment, students give feedback on different news stories. They check for language, narrative structure and editorial choices to assess how reporters conform to journalistic principles and best practices for Indigenous reporting. Word choice matters. When journalists write “so-called treaty rights,” instead of “treaty rights,” or use Canada’s Indigenous Peoples–as belonging to Canada–instead of Indigenous Peoples in Canada–as independent from Canada–they incorrectly frame the story and sow mistrust.

“You don't have to know everything,” says Roache, “you just have to know what you don't know and then know how to find that out. That's what we do as journalists.”

“I don't think anyone should graduate from university with any degree and not learn this stuff, to be honest,” says Roache. “If you're in a science program, you should still understand the basics of where you are and who the Indigenous Peoples are, if you're going to engage in research.”

Built on Mi’kmaw concepts

The course builds on an overview of Mi’kmaw culture and concepts, like “Ta’n weji-sqalia’tiek” which means “This is where we sprouted from,” to describe the intimate relationship between the Mi’kmaq and the land; and “Msit No’kmaq which means “All My Relations,” to describe the timeless connection between the Mi’kmaq, their ancestors, the land, the water, and all beings.

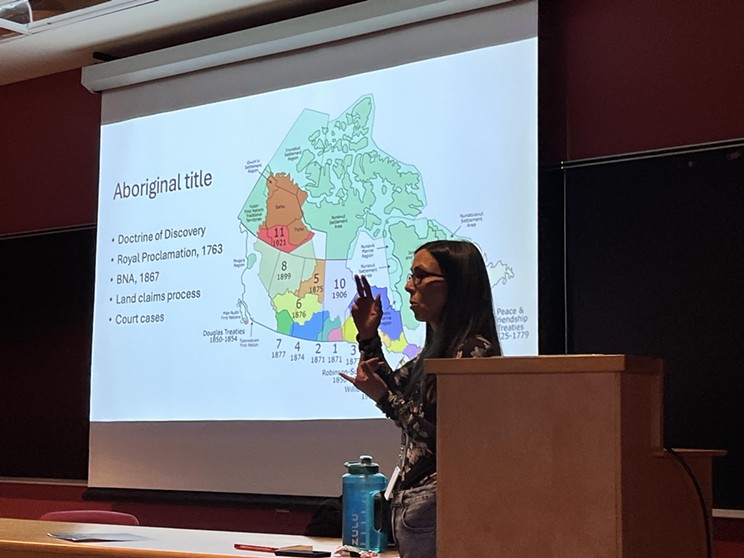

Students move through Mi’kmaw history and the larger colonial history of Canada that informs the lived experiences of people in Mi’kma’ki, which is all of Nova Scotia.

Students analyze how Canadian media talks about treaties in their coverage, delving deeper into key Mi’kmaw concepts and knowledge as well as Indigenous representations in media, including common stereotypes that pop up and recirculate.

Ainslie Nicholl-Penman is in her second year of a Bachelor of Journalism degree.

“The biggest thing that I've taken away from this course so far is how poorly a group of people can be represented in the media, and the perspective that can kind of be thrown into stories.”

In thinking about who can tell Indigenous stories, Nicholl-Penman says “I think that it's people that are taking courses like this one, and actively engaging themselves in a different culture. Those should be the people who should really be allowed to go report there,” rather than throw a reporter into a Mi’kmaw community who doesn’t know how not to use language incorrectly or continue false narratives around Indigenous Peoples.

Dheif Daniel Yunting is in the Master of Journalism at King’s and is Roache’s teaching assistant for the course. Yunting is an international student from the Philippines.

“To be perfectly honest, I had no idea that there were Indigenous Peoples in Canada growing up abroad,” says Yunting. “There was always this image of Canada that most of my friends had of Canada as this perfect country with acceptance of foreigners where opportunity is plenty.”

He says learning about Canadian media’s coverage of Indigenous Peoples over the years has “really been eye opening to me,” and is showing him a hidden side of Canada.

He says being Roache’s TA for the course has “really inspired me to the point where I'd like to write on Indigenous rights and Indigenous stories, although I also have to approach it in an appropriate way. I’ve learned that Indigenous Peoples tend to be a bit mistrusting towards the media, and I don't blame them considering how much coverage often doesn't paint them in the right way or doesn’t include Mi’kmaw or Indigenous voices.

“For example, if we go back to fishing rights, a lot of the time non-Indigenous people may not understand why the Indigenous folk are so riled up over fishing, and think, ‘They should follow what we do.’ And that's not really the case, but some stories don't explain it well.” Some do, he says, and that’s because they give time to contextualize or are written by Indigenous Peoples themselves.

This course is a step towards reconciliation and media. It teaches responsible reporting that can be applied to all types of learning, research and reading.

It also teaches students to remember the obvious: the who, what, where, when, how and why. Who lives here? Where are we?

However, this new mandatory course doesn’t settle the task of reconciliation and media at King’s. “There’s always more that can be done,” says Roache. She pushes back against the language of things being settled.

Treaties, for example, “they're not settled.” Or reconciliation. “It's not done with residential school closures. They can apologize, but that doesn't mean it's just done. A compensation deal comes because Canada just wants to be done, finished, and put in the past. That is a very Western thing.

“When it gets applied to Indigenous trauma, which can be ongoing, we're not ‘post-colonial’–everybody's still here.”